![]()

I began this blog in March of 2006 which means this coming New Year will mark the first full calendar year of writing, with posts having come weekly from January 2007 to December 2007. So, to commemorate and to join in with all the other Top 10 end of the year lists, here is a list of what I consider to be Experimental Theology’s Top 10 Posts of 2007:

#1: The Voice of the Scapegoat series

I began the year in the middle of my review of S. Mark Heim’s book Saved from Sacrifice which gives the church a Girardian reading of the cross. At the conclusion of that series I received the following e-mail from Mark Heim:

Dear Richard,

I'm writing with appreciation for your series on Girard and my book--one could not hope for a more graceful and thoughtful summary of Saved from Sacrifice, and I think there was much significant value added in your own reflections. It's wonderful to see such a response, and encouraging to think that there are others who find this as helpful as I do. It's a bonus also to discover your site and your other work there. I've known ACU only by my friend Doug Foster who is on the faculty of the Graduate School of Theology: now I'm glad to have this connection as well.

Under the Mercy,

Mark

For this gracious e-mail alone I vote this series The Best of 2007. Thank you, Mark, for your kind words. Keep the books coming!

#2 The Christ and Horrors series (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3)

This was a review of Marilyn McCord Adams’s wonderful book on Christology and theodicy. The critical feature of McCord Adams’ position is that God will be good to all horror participants. This leads to a universalist position which, in my opinion, is the only coherent move a Christian can make in confronting the problem of horrific suffering. This series got a nice plug from Keith DeRose at the Generous Orthodoxy Think Tank.

#3 Summer and Winter Christians

This was a single post summarizing a published paper of mine. The main thrust of the paper is to get Christian communities to reject simplistic polar models of faith (where doubt/negativity are antithetical to faith) and adopt a circumplex model where doubt/negativity can co-exist with faith.

#4 The Ecclesial Quotient

This was a quirky series where I try to create a mathematical formula to calculate your contribution to the Kingdom of God. I even graph the function. I like this series because it got noticed by a Network Theory class at Cornell University. When a theology blog shows up in a math class at Cornell you’ve got to be doing something right.

#5 Toward a Post-Cartesian Theology (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7)

In this series I review and interact with Harry Frankfurt’s book Taking Ourselves Seriously & Getting It Right. It is my best attempt (supplemented by my The Cartesian Race post) in grappling with the free will versus determinism debate. My work on these issues got noticed by Bob Cornwall who solicited an article from me on this subject for the pastoral journal he oversees, Sharing the Practice. The paper came out in the fall and was entitled “Ministry in the Post-Cartesian World.” Thank you Bob for asking!

#6 Theology and Evolutionary Psychology (Prelude, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8)

I don’t think Christians should be afraid of evolution. In fact, if you look at the Sermon on the Mount through the lens of evolutionary psychology you come away thinking that Jesus was a Darwinian genius. In this series I show how evolutionary psychology makes the Christian moral witness seem extraordinarily prescient, deep, and powerful.

#7 My Bible Class about Bob Sutton's Book

No retrospective on 2007 would be complete without facing up to my Most Controversial Post of the Year. I did a bible class at my church on Dr. Sutton's book and then followed that post up with a series. That post was picked up on by Dr. Sutton (initially here on his personal blog and then later in The Huffington Post where he mentions his changing attitudes about Christians in two features found here and here). Which pleases me in that, if you look at his remarks, it seems I helped dismantle some stereotypes about Christians and Christian intellectuals.

These gains aside however, because I didn't euphemize and took Dr. Sutton's language as-is (following the lead, as a scholar would, of the Harvard Business Review who first published Dr. Sutton's idea), some conservative readers have been offended and have written my employer about my Christian commitment. The disappointing part for me is that none of these complaints have been taken directly to me per Jesus' instructions in the Sermon on the Mount. Which means that the complaints are not Christian, honest, and truth-seeking in intent. They are, rather, attempts to use my post as a political tool against my university. Which is sad. To those offended by this blog, please e-mail me directly for conversation. Also note that my discussion of Dr. Sutton's book had nothing to do with my university as it was a bible class for my church, populated with adults and not college students. Thus, if you have any spiritual concerns with me on this topic please contact my spiritual overseers, the elders of the Highland Church of Christ. They are the ones accountable for both my spiritual journey as well as any teaching conducted under their oversight.

As a final thought on this subject, a part of the reason (other than its clear gospel message) I took up Dr. Sutton's book was to explore what "Christian language" can and should look like. What are the discernment issues involved? How do we adjudicate? Is propriety and politeness the main concern? But what if, as Dr. Sutton's book shows, cultural mores are changing? Is this a generational issue? If so, should language change to connect with the young even if the older (and most established in faith) are offended? These are challenging and important issues. How shall we speak to our world? Is the world a homogenous crowd allowing only a single form of Christian discourse? Or is the world heterogeneous, diverse, and ramified, requiring multiple languages each unique given context and audience? In short, all readers here--offended or not offended--should pitch in and discuss rather than gripe and complain. There is work to be done for the Kingdom! Let's find out how best to do it and support each other in a process--being in but not of the world--that necessarily creates different modes of missional living.

#8 Ghostbusting

For some strange reason I love this post from my Walk with William James series. (See the sidebar for all the installments. I would have listed the whole series but it's very long.) In this post I tell the story of my one paranormal adventure with some of my students.

#9 Everyday Evil (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6)

Lots of people seemed to really enjoy my Everyday Evil series where I show how the potential for evil is just around the corner for ordinary people. I have this series so low in the rankings because the YouTube clips that made the series so enjoyable keep getting taken away or moved.

#10 Why the Anti-Christ is an Idiot

The funniest post of the year.

So there it is, The Best of 2007. Thanks to everyone who has visited, read, linked to, and commented here in the past year. Look for more theological adventures in 2008. I have some fun stuff planned. See you after the New Year.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

Richard

Musings on the Scandal of the Body, Part 2: Looking for the Caganer in the Scene

If the body is an offense by being a death/mortality reminder then it is not surprising that many Christians show a strong sanitizing impulse when it comes to imagining their faith stories.

If the body is an offense by being a death/mortality reminder then it is not surprising that many Christians show a strong sanitizing impulse when it comes to imagining their faith stories.

We often see the sanitizing impulse in the depiction of Jesus' body. He's often handsome, well groomed, and clean, a veritable angel on earth. Thus, when artists, authors, or movie makers do try to take the Incarnation seriously and portray the body of Jesus (e.g., sexuality) the scrub brushes and soap of the Christian community rush out in alarm. Although our creeds claim that Jesus was fully human we don't want that truth depicted. The juxtaposition of the human and divine is just too offensive.

I've actually been on the receiving end of this sanitizing impulse. Two years ago at the ACU Lectureship I had the gall to suggest that Jesus, being fully human, would have experienced certain unpleasant intestinal issues, just like the rest of us. I made the observation that many would find this image offensive, blasphemous, and demeaning to Jesus.

Well guess what? ACU received a complaint about my talk. The reason? The person was offended that I suggested that Jesus might have experienced certain intestinal complaints. The given theological rationale was that Jesus would never have experienced such demeaning bodily functions/ailments because Jesus would have "healed himself." I find the irony here delicious. But irony and theological literacy aside, this is a good example of the sanitizing impulse. Apparently, you and I, humans with irksome bodies, have to reach for the Pepto-Bismol once in awhile. Jesus? Well, he's not like us. He heals himself. Jesus is superman.

Now during Advent preachers often reflect on the effects of the sanitizing impulse upon Nativity depictions. Most Nativity depictions hide the body. The barn scene is idyllic and clean. But we all know that the body was there in the Nativity. There was blood, amniotic fluid, and an umbilical cord. There was no running water or clean towels. Bloodied rags are heaped nearby. The barn smells of urine and manure.

You don't see much of that in Nativity scenes. To depict the body remains offensive. So, the Nativity is depicted as the superbirth of the superman. The Christian cleaning crews have thoroughly sanitized and scrubbed the scene for us.

So now--Hold on to your hats!--for a very quick shift toward the humorous, quirky, and cross-cultural, how might we combat the sanitizing impulse at Advent? Well, my friend Bill, knowing I'm always going off on the "scandal of the body", sent me this delightful little link about the Spanish tradition of the Caganer.

What better way of pushing against the sanitizing impulse this Advent season than dropping a Caganer into your home Nativity scene? (For a little more on the Caganer read here.)

Thanks to Bill for this delightful bit of Christmas cheer! I've been relishing in the theological whimsy of the Caganer, how the body, at its most offensive, is inserted into the hyper-spiritualized Nativity scene.

Oh, I'm sure the Caganer will be offensive to some. But for this Advent season the Caganer has reminded me, in a hilarious way, just what happened in the Incarnation. Just how far Jesus had to descend to experience the human condition.

And just how fully he participated.

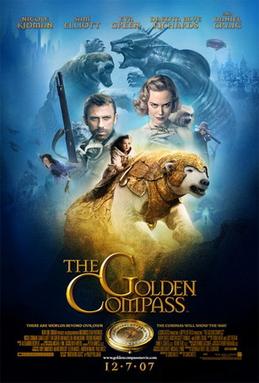

Ten Random Thoughts about The Golden Compass

#1

#1

There are two kinds of Christians in the world. Upon hearing (rightly or wrongly) that Pullman is an atheist who wrote a fantasy book about the death of God and the corruption of the church:

The first kind of Christian gets angry, boycotts the movie, and forwards cautionary e-mails to friends and family.

The second kind of Christian responds, "An atheist wrote it? Hmmm. That sounds interesting..." And then he goes and buys the book, reads it, and attends the movie with his friend Kyle to see what's up.

#2

My overwhelming impression of the book and the movie:

I like the armored bears.

#3

In a great twist of fate for this blog, science in Lyra's world (Lyra is the protagonist of The Golden Compass) is called "experimental theology."

#4

I'm just getting into the second book--The Subtle Knife--so this analysis is preliminary, but Pullman seems to be having fun conflating science and theology across Lyra's world and our own. For example,

Lyra's World :: Our World

Experimental Theology :: Science

Theologians :: Particle Physicists

Original Sin :: Dark Matter

Thus, scientific breakthroughs in Lyra's world are called "heretical" or "heresy." Which is an interesting thought as one ponders how religious fundamentalists view evolution...

#5

"Cutting" in the name of religion and for social control is a big symbol in The Golden Compass. The religious overtones echo circumcision and eunuchs. The social control overtones echo female circumcision and lobotomy.

#6

I don't see why Protestants are upset with the books/movie. Now Catholics, I can see why they are angry...

#7

There seems to be a lot of Eastern spirituality in the books. Dust, early in my reading of The Subtle Knife, appears conscious. Plus, Dust is what makes the alethiometer (the Golden Compass)--a tool of divination--work. In short, Dust seems like the Tao and the alethiometer is the I Ching.

#8

Pullman is mischievous with his depiction and naming of dæmons. Dæmons are soul-like animal companions all humans have in Lyra's world. The playful thing here is that the "demon" is the "soul." And the "church" is trying to "cut out" the "demon" to control the people. But, as we see in the book, what "the church" calls "demons" are really our "souls." Get it? The big bad church is trying to exorcise the demons of the world but they are (malevolently?) mistaken: They are actually killing people's souls in order to better control them.

This is an interesting little move but it's confused in that everyone in Lyra's world, even the church, knows dæmons to be good things. That is, although Pullman's move is semantically cute, it is narratively flawed. A church attacking what is universally believed to be a good thing isn't the church as we know it. It's a cult. But it is worse in Pullman's world in that even the church knows dæmons to be good things. Which means The Magisterium (the church) in Pullman's world is so confused as to have no recognizable counterpart in our world. In short, I think kids can safely read the books. Although The Magisterium is called "the church" in Pullman's books, it is so clearly NOT the church that when kids encounter The Magisterium they will immediately say, "That's not the church!" Which ultimately scuttles any attempt by Pullman (if he even had this intent) to undermine "the church" (as if there even exists a Magisterium-like "church" in this post-Christian world). (btw, that is my general take on a lot of Pullman's playful, multi-layered symbolism: Cute, but structurally flawed by his own hand.)

#9

But the most interesting thing about dæmons is how they echo Christian orthodoxy about the fundamental features of the Imago Dei. More specifically, dæmons evoke notions of the Trinity. That is, in the doctrine of the Trinity God is never "alone." God is defined as a community. In Lyra's world human personality is always communal. People are not singularities. Loneliness doesn't exist.

#10

Final verdict?

I prefer non-fiction. But I do like the armored bears.

Musings on the Scandal of the Body, Part 1: Why We Curse

As a psychologist I tend to muse, theologically, about the stuff of life. One facet of human existence that I've been intrigued with has been cursing and profanity.

As a psychologist I tend to muse, theologically, about the stuff of life. One facet of human existence that I've been intrigued with has been cursing and profanity.

Specifically, why is profanity so scatological and sexual? Obviously, the sensory aversions we have toward human waste may be the simple associative reason for scatological references. But this analysis doesn't help us understand why sexuality is so often implicated in profanity. So, to my mind, there seems to be more going on. I've posted about this topic before and was prompted to revisit this topic by a recent book published by Steven Pinker.

Pinker, psychology professor from Harvard, is one of the most influential psychologists working today. Pinker's books The Language Instinct, How the Mind Words, Words and Rules, and The Blank Slate are all worth reading (for theologians I highly recommend The Blank Slate). Recently, Pinker released a new book, The Stuff of Thought. In The Stuff of Thought Pinker has a chapter on the psychology of profanity and cursing. That chapter was recently published as an article for New Republic. Pinker's New Republic article can be found here. It is a great read.

Although Pinker's article is a fascinating survey of the cognitive science of profanity he fails to crack the mystery of why profanity is so scatological and sexual. Many of those deep questions remain.

My contribution has been to suggest that part of the mystery surrounding profanity can be revealed if we examine it from an existential perspective.

Specifically, as I've written about before, psychologists have amassed evidence that the body is a mortality reminder. That is, the body, with its waste, smells, ooziness, and vulnerability, makes our animalness salient. We find this degrading and fearful. Man wants to be an angel. Profanity cuts through those illusions. This is the source of the offense.

To profane something is to strip off the spiritual overlay, to make something sacred base and common. Profanity desacralizes human beings. For example, to call a woman a f****** b**** is to take someone made in the Imago Dei, to be encountered as a mysterium tremendum, and reduce her to a barnyard animal in heat. This is the offense of profanity, its desacralizing maneuver.

But profanity not just degrading. In my analysis, the degradation is filled with existential significance. To be reduced to an animal creates an existential dread: Am I ONLY an animal? If so, do I have a soul? And if I don't, what happens to me at death? In short, profanity is a death reminder and this, too, is an offense.

Profanity is a theological act. In its offense we find body and soul, the animal and the divine, and death and resurrection dancing in a dialectic.

Theology can be found in the most unlikely of places.

Musings on Openness Theology, Part 6: S-Fact Blindness and the Incarnation

Similar to what I did in the last post, I'm going to make an argument for openness theology without recourse to free will.

Similar to what I did in the last post, I'm going to make an argument for openness theology without recourse to free will.

Actually, the position I'm going to argue for is not, technically, an openness theology formulation. It is, rather, a position that captures much of what is being sought for, theologically speaking, from openness theology.

This argument is going to be based on what is known as the Hard Problem of Consciousness.

Part 1: p-Facts and s-Facts

The Hard Problem of Consciousness, a term coined by David Chalmers, refers to one of the most notorious issues in neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and the philosophy of mind. Specifically, the problem points out the explanatory disjoint between the methods of reductive science and the subjective experience of mental states.

Science, as a method of inquiry, relies on public, third-party adjudication. That is, Fact X or Outcome of Experiment Z should be repeatable and replicable under controlled and identical conditions. When we see Fact X or Outcome of Experiment Z repeated and replicated over and over the scientific community reaches a public consensus about the phenomenon under consideration. Let's call these p-facts (p for "public-facts").

Science only traffics in p-facts. Anything that can't fit into the box of p-facts (e.g., ghosts, God, historical events) cannot be scientifically evaluated. Science is just a one trick pony: Grinding out and adjudicating between purported p-facts.

Now it should come as no surprise that science would like to investigate the workings of the human mind. And to a large degree many of the p-facts of human brain functioning and cognition have been revealed. For instance, we know that Broca's area in the left hemisphere of the brain is involved in speech production. Damage in that area leads to aphasia. This correlation--brain location and function--is a p-fact. Neuroscientists have public access to the evidence supporting this p-fact.

But there are certain aspects of the brain that we would like to study which don't appear to be p-facts. I'm referring specifically to what psychologists calls "sensation" (other names are "qualia," "experience," or "phenomenological experience"). Sensations are our raw sensory experiences: Visual, auditory, olfactory, etc. Take the classic example from the literature: Red. "Red" is a sensory experience. We experience it when we see an apple or a rose. But what does red look like? What accounts for its particular "color"? How exactly is red different from blue?

The "sensation of red" is clearly a fact about the word. And it's a repeatable phenomenon, unlike a historical event, that should be amenable to scientific research. It should be a p-fact. But, notoriously, it's not a p-fact. It's an s-fact (s for "subjective-fact" or "sensation-fact").

All sensations are s-facts. That is, they are private. They are not public like p-facts. I can't get into your head to "see" what red looks like to you. Note, however, that there are a host of p-facts about color sensation. For example:

Some p-Facts about Color Perception:

(i) The neurological events in the eye can be correlated with certain wavelengths of radiation (i.e., we know about rods and cones--the photo-receptor cells--in the eye)

(ii) The correlation between brain events in the occipital lobe and exposure to certain wavelengths of radiation (i.e., when you look at color slides we can observe and correlate those exposures with events in the brain seen via brain imaging devices).

(iii) The correlation between verbal tags and exposure to certain wavelengths of radiation (e.g., You always say "red" when you are exposed to a certain wavelength of radiation).

All these are p-facts. These are events and experiments that are amenable to science. But notice, none of these p-facts can tell us just why red looks different from blue. That distinction is an s-fact.

The perversity of the situation is this: Since science only traffics in p-facts we will never, ever, gain a scientific account of sensation. This is perverse because it seems that sensation, being a regular feature of the mind, SHOULD be amenable to science. Yet it is hard (hence the name "Hard Problem of Consciousness") to imagine a way that science could explain s-facts. There is a disjoint between the public nature of scientific adjudication and the private nature of sensation. The tool--science--and the material--sensation--just don't match up.

Chalmers puts it this way. Even if science could perfectly explain all the p-facts of the human mind there would still be something LEFT OVER, something EXTRA, that is involved in human cognition: All those s-facts. Science might, one day, know with perfect precision the exact neural correlates of all s-facts. That is, from a third-party perspective I might track with perfect knowledge the molecule by molecule changes in your brain when you see a rose. But observing those molecular changes still does not reveal to me what red looks like to YOU. The s-fact of red cannot be cracked open with better and more powerful brain scans. Staring at a bunch of neurotransmitters isn't going to tell you why red looks different from blue.

Part 2: The Omniscient Neuroscientist Who Sees Only Black and White

Now what does all this have to do with openness theology? Well, I'm going to borrow a common thought experiment from the Hard Problem literature and adapt for a theological purpose.

Here is a two-part thought experiment:

Part A: Imagine a neuroscientist with perfect knowledge of the human brain. That is, this scientist has perfect brain imaging capability and had performed all the requisite experiments. Further, this scientist knows all the Laws of the Mind: For each and every stimuli the mind faces this scientist can predict with perfect accuracy the activity of the brain.

Part B: Now imagine that this scientist, from birth, has been wearing goggles that renders the world in black and white.

Okay, first verify for yourself that Part A and Part B involve no contradiction. That is, you don't have to know what red looks like, subjectively speaking, to have perfect scientific knowledge of color vision. The scientist can verify which "color" a subject is seeing by noting the p-facts. For example, "red" is simply the wavelength of radiation the person is being exposed to, something that can be assessed with a measuring instrument (i.e., "red" is defined as a public event--a reading on a scientific instrument--and not as a private, subjective experience).

This is the point of the thought experiment: You can have perfect, objective, scientific, p-fact knowledge of color vision and still not know what red looks like. (btw, this thought experiment is just another way of framing/illustrating the Hard Problem.)

Now imagine that we ask the neuroscientist to take off, for the first time in her life, the black and white googles. (For the sake of argument, let's put aside the neurological/developmental issues of depriving someone of color vision from birth.) Could the neuroscientist, who has PERFECT scientific knowledge of color vision, even predict what a world of color looks like? It would be like going from Kansas to Oz.

Now we can ask this question: By taking off the goggles did the neuroscientist LEARN something? Sure they did! They learned what red looks like! And they learned this in the only way possible: By stepping into the experience. The only way to "learn" an s-fact is to EXPERIENCE it.

Part 3: God and s-Facts

Can you see where I am going with this? The perfect neuroscientist is an omniscient scientist. Well, more precisely, an omniscient p-fact scientist. (Because the scientist, prior to the removal of the goggles, doesn't know the s-facts.) So here is my question: Is God in any way analogous to the omniscient p-fact scientist?

That is, by creating humans did God--in possession of all p-facts--create the possibility for ANOTHER set of facts--s-facts--that God did not have access to? What I'm suggesting, in contrast to free will arguments, is that the universe, humans in particular, is more inexplicable to God than unpredictable. The reason for this is that God created a set of facts--s-facts--that he did not have access to. God retains all objective, p-fact knowledge, but God is (initially at least) shut out of the "human experience." God does not know, first-hand, what it "feels like" to be a human being. And if God were shut out from s-facts then there would be a critical relational disjoint between God and humanity which might explain much of the biblical witness.

If this analysis is correct it produces fruit similar to (and in some cases better than) openness theology positions.

For example, the debate between classic theism and openness theology often pits God's omniscience against the biblical witness that God experiences emotions and changes his mind. For example, if God knows the future how can God be emotional in the face of human actions? God should be impassive, right? But the Bible clearly grants God emotions. Does God, then, not know the future? If he doesn't, then how can he be omniscient?

In short, the debate between openness theology and classic theism pits two biblical claims--God has emotions and is omniscient--against each other. And it is hard to reconcile the two.

But let's look at the issue from the s-fact perspective. First, God is p-fact omniscient. As such, he can probably predict the future perfectly. The trouble is, due to God's s-fact blindness, the future unfolds in a way that puzzles God. Without s-fact knowledge God can predict the next moves of creation but something critical is missing. That is, God might know--as a p-fact--that A will follow B in the chain of events. But what is left out is the critical feature of "Why?", from an s-fact perspective. For example, A follows B because B hurts!

Think back to the neuroscientist, but now imagine we could block out ALL s-facts, not just those about color vision. Although the neuroscientist could explain all the relevant p-facts of, let's say, pain sensation, can she really understand why we pull our hand away from a hot stove? Isn't something, from an explanatory perspective, being missed? I think so.

Now I don't think God is completely s-fact blind. But I do think God has SOME s-fact blindness. For example, can God know what it is like to be scared? To experience pain? Nostalgia? Pride? Temptation? Embarrassment? Shame? Guilt? Old age? Giving birth?

In short, I think in certain critical areas God starts off as s-fact blind and this blindness can explain much of the Old Testament witness regarding God's emotions and responsiveness to humanity.

Specifically, due to s-fact blindness God initially finds us alien and Other. Thus, the emotions of God in the bible and his changing plans are less about his being "surprised" than about a God's wrestling with something foreign and strange. God seems to be trying to "figure us out." And as the process unfolds God reacts with surprise, delight, anger and frustration.

In my opinion, this sense of "foreignness" better expresses, when compared to free will formulations, the relational dynamic between God and humanity. In openness theology relationality is believed to be preserved by the existence of free will. But God's s-fact blindness, in my view, is a better model. For example, when I first met my wife (or my children or a new friend) the issue, relationally speaking, is not if the two of us have "free will." The issue is, rather, "Who is this person?" Relationality is a process of intimacy and intimacy is a process of discovery. More specifically, it is a process of discovering the internal life of the beloved. We call this "understanding." To understand my wife is to take her perspective, to "get inside", as best I can, her unique take on the world. What starts out as foreign, a literal stranger, eventually becomes my beloved. In short, according to my s-fact model relationality with God doesn't emerge because we are free (although we may be), but because God and I start out as strangers. God is trying to know me and I'm trying to know God. And this is accomplished in a way analogous to human intimacy: Taking two distinct experiences and bringing them together. To be intimate is to learn, as best I can, your s-facts.

Part 4: Is God Growing More Kind?

Another interesting application of s-fact blindness is that it might explain some of the perceived disjoint between the Old and New Testaments.

Specifically, Christians claim that God is love. Yet, God's expressions of love seems radically different in the Old versus the New Testament. Crudely stated, God seems more kind in the New Testament. Why is this?

Many answers have been proposed to this question. S-fact blindness might be another. That is, God has always been loving. But God's ability to love humanity, early on, has been affected by s-fact blindness. God, literally, could have made some mistakes early on. Not because God is evil or incompetent, but simply due to the early missteps that occur in any new relationship where two people find each other as unpredictable strangers. Relationships are messy due to s-fact blindness. Perhaps the same goes for God and humanity.

Part 5: What Does the Bible Say?

This all seems so abstract and philosophical. Does this perspective have any biblical support?

Hebrews 2

But we see Jesus, who was made a little lower than the angels, now crowned with glory and honor because he suffered death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone. In bringing many sons to glory, it was fitting that God, for whom and through whom everything exists, should make the author of their salvation perfect through suffering. Both the one who makes men holy and those who are made holy are of the same family. So Jesus is not ashamed to call them brothers...Since the children have flesh and blood, he too shared in their humanity so that by his death he might destroy him who holds the power of death—that is, the devil— and free those who all their lives were held in slavery by their fear of death. For surely it is not angels he helps, but Abraham's descendants. For this reason he had to be made like his brothers in every way, in order that he might become a merciful and faithful high priest in service to God, and that he might make atonement for the sins of the people. Because he himself suffered when he was tempted, he is able to help those who are being tempted.

Hebrews 4

Therefore, since we have a great high priest who has gone through the heavens, Jesus the Son of God, let us hold firmly to the faith we profess. For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are—yet was without sin. Let us then approach the throne of grace with confidence, so that we may receive mercy and find grace to help us in our time of need.

Did God learn something in the incarnation? If so, what did God learn? According to my model, God learned about the s-facts of the human experience.

Is this not what the book of Hebrews is speaking to? That Jesus is a more perfect High Priest because Jesus has experienced the s-facts? Hebrews seems to suggest that God learned something in the Incarnation that was vital to his ability to be a good God to us. And what God seemed to learn is what it "feels like" to be a human.

Because of the Incarnation God is less s-fact blind. And, via the intercession of Jesus and the Holy Spirit, the human experience is able to be "translated." God now "understands" us.

Musings on Openness Theology, Part 5: The Quantum and Algorithmic Compression

The conclusion I reached in my last post is that I don't feel conformable, personally speaking, building theological structures upon free will. Again, this is not to say that free will doesn't exist. It's just that people dispute free will and if you want your theology to have broad intellectual appeal you can't have a whopper sitting right there in the middle of it. Christians are notorious for their cavalier deployment of free will and it hurts our intellectual credibility. So regular readers know that in this blog I routinely problematize free will, trying to resist cavalier deployment.

The conclusion I reached in my last post is that I don't feel conformable, personally speaking, building theological structures upon free will. Again, this is not to say that free will doesn't exist. It's just that people dispute free will and if you want your theology to have broad intellectual appeal you can't have a whopper sitting right there in the middle of it. Christians are notorious for their cavalier deployment of free will and it hurts our intellectual credibility. So regular readers know that in this blog I routinely problematize free will, trying to resist cavalier deployment.

Okay, so I put free will on the sideline as not good working material. Could I find a way to go forward with an openness theology model? What follows are a few of my "theological experiments" on this topic.

The first notion I played with had to do with algorithmic compression. This idea comes from informational approaches to entropy. Specifically, entropy is the amount of randomness and disorder in a system. Scientists have long searched for ways to try to describe and quantify entropy. How can you tell how much entropy (disorder) there is in a system?

In computational physics the idea of algorithmic compression was hit upon as a measure of entropy. Imagine that the universe and its laws are just one big computer program. What we take to be "events" are just "computations", taking in input and producing output moving the "program" into the next configuration. And so on and so on. If we see the universe as a large computation, churning away through time, then perhaps the findings regarding informational entropy and algorithmic compression might apply.

Specifically, in purely informational terms, how much entropy/disorder/randomness exists in a data string? How could this be measured?

The breakthrough idea in this area was the notion of algorithmic compression. The basic idea is this: The degree to which a program or data string can be compressed is a measure of its entropy. Let me give you some examples.

Data String #1: 100 X's

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Clearly, this data string isn't very random. It doesn't have a lot of disorder or entropy. As as a result, it can be compressed. That is, you could write up a little program that produces that data string. It might look like this:

PRINT "X"

LOOP N = 100

END

You have here a little program that is the informational equivalent of Data String #1. But notice the difference in compression. Data String #1 has 100 characters and the program compresses to 20 characters. Note the idea: Low Entropy/Randomness = High Compression.

Now imagine a more random data string:

Data String #2: 100 Seemingly Random Letters

PHMVUFTCGXRSEWDZXASZEXRCTVGFBGHBYHNJKMIOKLJPHUERXC

HFYDREVSEXYFHAWQCXVHIUKHOMPNKHUGYVBGCTDVXIGOJPGID

The question is: Can you compress this?

The answer is, probably so. Although I tried to be random in my pecking at the keys I doubt if I achieved that. So it is probable that this string could get compressed. But not by much. Note the idea: High Entropy/Randomness = Low Compression.

Okay, now the take home point: What if a string of data were perfectly random?

If a string were perfectly random then it could not be compressed. Which is to say that the shortest way to describe a random program is to actually run the program and see what it will produce. For example, we don't need to run our program for Data String #1. Recall:

PRINT "X"

LOOP N = 100

END

We don't need to run this program to see what it will produce. The program is compressed, but it captures all the relevant information. But a random data string can't be compressed. To describe the program (i.e., to look at what it will produce) we have to run/execute the program. To describe and know is to compute.

Where am I taking all this? Well, here was my thinking. Maybe we can approach openness theology through the lens of algorithmic compression. That is, consider the universe to be like a computer program. Maybe God is passable (i.e., emotional) as the future unfolds because of low algorithmic compression. That is, if the universe can't be compressed very much then the only way to describe how the universe will unfold is to actually let it unfold. As we learned, to describe and know is to compute.

This is a very subtle point. What this argument is saying is that God's creation of Creation and knowledge of Creation are the same thing. This idea conflates describing, knowing, and computing/excuting/running the Creation "program." God knows/creates as the program unfolds. Phrased another way, God is creating right now. Creation isn't a point in the past. Creation is the unfolding, it is ongoing. God's knowledge and creating are synchronized. If so, God can be suprised by his Creation. God cannot know the outcome of the Creation "beforehand." Why? Because to describe/know the program is to actually run the program. Running Creation and knowing Creation are the same thing. God creates to know. He knows by creating. And, according to openness theology, God reacts/adjusts to the unfolding accordingly. Thus, God's interventions are not post-hoc "fixes" (as Hume famously complained about). God's interventions in the world are acts OF creation.

But here's the problem. This model only works if the universe is not compressible. But it clearly is. Look at Newton's Law of Gravity. It's a beautiful compression. All the laws of planetary motion compressed in a neat little formula. The movement of the spheres is not disorderly, random, and entropic. The movements of the spheres can be compressed. We call the compressions the Laws of Nature.

But then I wondered. Newton's Laws don't really hold, do they? Quantum Mechanics tells us that the universe, at its most elementary level, is random. And not pseudo-random, really, truly random. If this is so, maybe the universe resists compression. Maybe the Plank Constant sets a limit on how compressed the universe can be. Perhaps the universe can be compressed to a point, allowing short-term prediction, but ultimately resisting long term prediction via the mechanisms of chaos theory. (See my prior post for this discussion.)

And this is as far as I have gotten. Basically, I put aside free will and wondered if I could build an openness position by appealing to algorithmic compression, the quantum, and chaos theory.

This is the kind of stuff I think about in the shower...

Musings on Openness Theology, Part 4: Forecasting, Laplace's Demon, and Omniscience

Okay, the next few posts are going to get really technical. Sorry. I'm adding a lot of links so you can explore.

Okay, the next few posts are going to get really technical. Sorry. I'm adding a lot of links so you can explore.

We've overviewed the basic tenets of openness theology. Specifically, right now God does not know the future. Either because the future doesn't exist (presentism) or because God doesn't know which timeline we humans will pick out of the infinity of timelines God holds in his mind (like Robert Frost's two roads in a wood only much, much more ramified).

Now the mechanism for these positions is human free will. That is, God, desiring true love and relationship, gave humans free will. By making us "free" God cannot predict what our choices will be. In some way God is epistemologically bounded by free will. In presentism (i.e., the future doesn't exist) free will limits God's ability to calculate the next moves of the universe (i.e., the future might not exist but given what is happening now God should be able to act like a weather forecaster with perfect knowledge). In the ramified timeline view, God has already calculated out all possible futures but cannot predict, due to free will, which branch in the road humans will choose.

This seems to be a great theological move. By positing free will we reap the following theological riches:

1. God's passability (God has emotions) and relationality

2. A theodic attenuation where human (and, for Gregory Boyd, demonic) freedom becomes much more implicated in evil/pain thus attenuating the theodic burden on God.

However, how tenable is free will? Should an entire theological position--something on which faith rests--be built atop one of the most controversial and notorious philosophical constructions in the history of human thought?

Doesn't seem like a wise idea to me.

I don't want to get into all the objections about free will but let me make a few psychological comments about its problems.

The main issue I'd like to talk about has to do with prediction and selfhood. First, you can't build a coherent self across time with free will. My choices today have to coherently flow out of who I am at this moment in time. If my next choice is radically free, so free that an omniscient God is 100% clueless about what I'll do next--then my personally disintegrates into a schizophrenic nightmare. I'm not just going to stand up, at random, and shoot my family. It's just not in the cards. My will isn't free. If anything, my will is tightly constrained, flowing through narrow channels. Channels we call "identity" and "selfhood."

A bit of personal observation makes this point. Even I, a lowly human, can predict my wife's reactions into the future. And she can, hopefully, predict mine. If we had free will we would wake up each morning facing a stranger. We'd be starting over each day. Free will is like a chalkboard that keeps getting erased. No history, no memory, no constraint. Rather, this moment of choice is radically open. Terrifyingly, horrifyingly, incoherently, and incomprehensibly open.

In short, the choices are not free. The future self flows out of the past self in a coherent fashion. The world isn't a causal kaleidoscope.

Thus, as I see it, when we speak about the "openness of the future" what we are really discussing are issues of prediction and forecasting. That is, even with presentism God should be able--because the future flows out of the past--to "weather forecast" (but for human relations; Asimov fans can think of Hari Seldon's psychohistory in the Foundation series).

Humans can forecast. We do it for the weather and we do it when we predict how friends, co-workers, and family members will react to things we say or do. And we pull this off quite well most of the time.

But human forecasts are not perfect. The future is open for us in that our forecasts can err. Further, our forecasts tend to get less accurate the farther we extend them into the future. And this goes for both meteorological and psychological forecasts. I can predict with almost 100% certainty that I will love my wife tomorrow. But what about in 50 years? Given divorce rates, people have been wrong about these forecasts. (Jana, baby, you know we'll still be in love 50 years from now! I'm in that academic mode you hate. Forgive me!)

The reason human forecasts err and fail to extend far into the future is largely due to measurement issues. We cannot measure with infinite precision all the meteorological variables needed to make perfect predictions. Rather than measuring the exact features of all the mico-variables (e.g., the location and speed of each and every water molecule) we deal with macro-level features: Barometric pressure, cold fronts, temperature, humidity. The same ideas apply to psychological prediction. I don't measure the exact features of my wife's mico-level variables (e.g., neurotransmitters, synaptic configurations and strength). Rather, I deal with macro-level features: Personality traits, likes, needs, habits, etc. Focusing on these macro-level features--meteorological or psychological--involves a lot of "rounding" (e.g., when measuring a board you don't measure with infinite precision, we round off) which makes the system potentially chaotic. That is, in physical systems with sensitive dependence upon initial conditions, small rounding/measurement errors cause the system to evolve in ways that diverge from short-term predictions (in fact, the Lorenz attractor, the first big breakthrough in chaos theory was a model of the weather).

The point is, prediction is related to information/measurement. Chaos theory tells us that in certain systems our epistemic limitations will limit our prediction. We will never we able to predict the weather (or people) because we'll never be able to measure the system with perfect precision; we'll always be "rounding."

But God is omniscient and should be able to measure with infinite precision. If so, God should be able to predict/forecast the future with infinite precision.

This ability to forecast the future was described by envisioned by Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1814. Specifically, Laplace speculated that if an intelligence COULD know all the relevant information in the world this intelligence would be able to predict/know the future:

"We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes."

This intelligent being is known as Laplace's demon. For Christians it simply looks like omniscience.

So here is the dilemma. Free will seems to be a non-starter. I offered some psychological critiques but there are others. But on the other end of the spectrum we have Laplace's demon and omniscience. Neither seems like good options.

Is there any way to move ahead?

Hmmmm.....

I had no time to Hate

Musings on Openness Theology, Part 3: Models of Sovereignty at Church

John Sanders takes a slightly different approach to openness theology in his book A God Who Risks: A Theology of Providence. Sanders tries to de-emphasize the focus on foreknowledge and the future. He focuses rather on issues of sovereignty and the kind of world God has chosen to create.

John Sanders takes a slightly different approach to openness theology in his book A God Who Risks: A Theology of Providence. Sanders tries to de-emphasize the focus on foreknowledge and the future. He focuses rather on issues of sovereignty and the kind of world God has chosen to create.

Specifically, Sanders contrasts two views. First, there is Specific Sovereignty (SS). In SS God is micro-managing the world. God is willing, guiding, and directing "the specifics" of life. Every little event is the will of God. Sanders calls this the "no risk" view of God. With SS the universe evolves exactly as God has planned. With there being no wiggle-room in the world--no deviation, no surprises for God--God risks nothing in creating this world.

Although the SS (no risk) world preserves a view of God's transcendent perfection and power the no risk view has some problems. Theodicy comes to mind. If every event is decreed by God then, well, some events don't seem to fit. God willed the Holocaust? Children with cancer? School shootings? Rape?

Further, the no risk world sucks the relationality out of the cosmos. Do we have any real choice in this world? Would prayer mean anything in this world?

The no risk world also complicates issues of salvation. If only some people are going to heaven and all things are being willed/directed by God why isn't God willing for the salvation of all? Why is he arbitrarily picking an elect few?

In contrast to the SS model, Sanders sets out the General Sovereignty (GS) model where God is macro-managing the world. That is, God's activity is the world is at a larger scale. God is working out his purposes in a world where he has turned over much of the control to humanity. God has, to a a degree, withdrawn from the world to allow humans scope. God does this to create spontaneous relationships.

In this GS world God is taking risks. With humans driving the car much of the time God is responding to the consequences of our individual and collective choices. Obviously, God's biggest risk in creating this world is allowing human sin, the rejection of God, to become possible.

The GS world where God takes risks seems to do a better job than SS with the issues we noted above. God didn't cause the Holocaust. Humans did. God hated that the Holocaust happened. Further, God didn't abandon us to those choices. He was there, in the Holocaust, working out his purposes while preserving the relational aspects of the world he created. Also, in the GS model God truly does seek the salvation of all humanity. He's not picking out the elect. Salvation is reciprocal with humanity left with the choice to respond to God.

In my next post I want to start picking apart the openness theology position. Not to reject it but to try to reconfigure it. But before turning to that task I want to pause and reflect on how people react to the SS and GS models.

Curiously, the SS and GS models have very different effects on believers. And I'm fascinated by this.

Let's start with SS, where every event has been decreed by God. Personally, I'm appalled by this view. Again, the theodicy issues just seem too problematic for me. And yet, I've seen some very good people, friends of mine, grab onto this view as a theodicy.

For instance, a family at our church, friends of ours, have a child who is afflicted by cancer. In a SS world God willed for this child to have cancer. Again, I can't go there. But this family, the people living daily in the face of this situation, are very strong SS people. They hold onto the view that God must have a reason, a purpose for this illness. God has a plan for all this.

And this perspective gives them hope and courage. It has allowed them to get up every morning and care for their child and sit through hours upon hours of doctor consultations and surgeries. That God has a plan is what gives them strength and hope.

Theologically, I have some doubts about all this. But I keep my mouth shut. Their faith and courage humbles me. And my academic quibbles about models of God's sovereignty are obscene in their presence.

By contrast, there are parents in similar circumstances who simply must reject the SS model in the face of their child's illness. If God willed for this to happen then God is a monster.

The point is, in my experience, in the midst of horrific suffering different kinds of people are either attracted to or repelled by specific sovereignty. People tend to take one of two roads in the face of suffering and it manifests in diametrically opposed ways. Which is both curious and communally difficult. Two families in pain. One claiming it was God's plan and the other horrified at that same claim. Both in the same communal space. Which is bound to create confusion and pastoral challenges.

It really is quite a pickle. In any given church, emotionally raw people are deploying diametrically opposed models of God that each finds theologically and psychologically repulsive.

Musings on Openness Theology, Part 2: The Odd Case of King Saul

Before proceeding deeper into theological waters it might be helpful to dip into the biblical witness to highlight some issues, problems and tensions. Rather than attempting an exhaustive biblical review, let's just muse over a single biblical story: The rise and fall of King Saul, first king of Israel.

Before proceeding deeper into theological waters it might be helpful to dip into the biblical witness to highlight some issues, problems and tensions. Rather than attempting an exhaustive biblical review, let's just muse over a single biblical story: The rise and fall of King Saul, first king of Israel.

Part 1: Contingent Futures and Impetratory Prayer

The story begins in 1 Samuel 8:

When Samuel grew old, he appointed his sons as judges for Israel...But his sons did not walk in his ways. They turned aside after dishonest gain and accepted bribes and perverted justice.

So all the elders of Israel gathered together and came to Samuel at Ramah. They said to him, "You are old, and your sons do not walk in your ways; now appoint a king to lead us, such as all the other nations have."

But when they said, "Give us a king to lead us," this displeased Samuel; so he prayed to the LORD. And the LORD told him: "Listen to all that the people are saying to you; it is not you they have rejected, but they have rejected me as their king. As they have done from the day I brought them up out of Egypt until this day, forsaking me and serving other gods, so they are doing to you. Now listen to them; but warn them solemnly and let them know what the king who will reign over them will do."

Samuel told all the words of the LORD to the people who were asking him for a king...

But the people refused to listen to Samuel. "No!" they said. "We want a king over us. Then we will be like all the other nations, with a king to lead us and to go out before us and fight our battles."

When Samuel heard all that the people said, he repeated it before the LORD. The LORD answered, "Listen to them and give them a king."

Summarizing the relevant details of the story: God desires a future without a king. The people disagree and insist on having a king. God warns them about this but eventually agrees.

This story highlights a few issues relevant to openness theology:

1.) God might have a desire/plan for a future that might not come to pass.

2.) God's plan might be thwarted or at least set aside in the face of human demands/requests/prayers.

3.) God might desire an optimal future but allow a sub-optimal future to come to pass.

In sum, this story seems to suggest that God might see a way forward--His preferred way, and one that is best for us--but set that future aside in the face of human request. Even if this new future is bad for us. Which is scary if you think about it. Rather than Garth Brooks' "Thank God for unanswered prayer", what about "Thank God I never prayed in the first place"!

These questions go to what is called impetratory prayer. That is, as John Sanders frames it, does God ever do something he was not planning to do just because we asked for it?

Some Christian thinkers deny impetratory prayer, stating that God's will never changes. By contrast, impetratory prayer suggests that God might have a preferred future yet set it aside to act relationally with humanity. I Samuel 8 seems to support this view. God did not want Israel to have a king, it was not God's will. Yet, to allow humans input into their future God sets his will aside and allows the future to evolve in a different, even sub-optimal, direction.

Part 2: Does God Regret and Change His Mind?

God, now allowing a king, eventually selects Saul. However, in 1 Samuel 15, after repeated failures on Saul's part, we see God regret and then change his mind as to who should be king:

Then the word of the LORD came to Samuel: "I am grieved that I have made Saul king, because he has turned away from me and has not carried out my instructions."

The word "grieved" is variously translated as "regret" (NRS, NASV) or "repent" (ASV, KJV).

Now the issue, obviously, is why did God not see this coming? Is God really regretting his choice? Did God make a mistake? Was Israel's bad choice--wanting a king--exacerbated by a bad choice--selecting Saul--by God? Or was the future placed contingently in the hands of Saul? That is, the bible seems to blame Saul, not God, for this outcome. If so, God could be properly regretting and grieving the future Saul has selected for himself and his nation.

Interestingly, in the middle of this story we get a counter-testimony about God changing his mind. After Samuel informs Saul that he is no longer to be king, Saul repents and tries to change Samuel's mind. It doesn't work. So, as Samuel turns to go Saul grabs his robe to pull him back. The robe tears and Samuel turns around in anger and speaks these words:

"The LORD has torn the kingdom of Israel from you today and has given it to one of your neighbors—to one better than you. He who is the Glory of Israel does not lie or change his mind; for he is not a human being, that he should change his mind."

Now this is a very confusing passage. God doesn't change his mind? This whole story is about God changing his mind! In the final verse in the chapter, just five versus away from this speech from Samuel, the text says this:

"And the LORD was grieved that he had made Saul king over Israel."

That is, the whole story is book-ended by God regretting his choice about Saul and pulling Saul out of the kingship. Yet, in the middle of the story we get this testimony that God, being God, doesn't change his mind.

I bring all this up to make a couple of observations.

First, it is no easy thing to lift a verse from the bible and make sense of it. A person, in a debate about openness theology, might throw this quote at you:

"The Glory of Israel does not lie or change his mind; for he is not a human being, that he should change his mind."

And yet, this quote is embedded in the very heart of a story where God actually did change his mind. More, God grieved and regretted this choice. Even more, this whole history wasn't even a part of God's plan. This whole timeline--the establishment of a king--wasn't God's will at all.

Second, and this just follows up with the prior point, the biblical witness regarding the openness of God is very mixed. Which is probably why there is so much debate, confusion, and diversity on the matter. At times the bible seems to assert that the future is open. So radically open that God will set aside his plan--No king--and allow a sub-optimal future--King--to evolve. What kind of view of Providence does that set up? And yet, the bible is also clear in saying that God doesn't change his mind like humans do. Hmmmmm....

So what is the answer? I take my cue from theologians like Barth who state that the mixed message we are getting about God in the bible is intentionally mixed. That is, God can't be systematized. God is free. Nothing will interfere with the Divine Prerogative. That doesn't answer all the questions, but it does say that once we make up our minds about what God can or cannot do, God will thwart that theological configuration. So in the end all we have is this:

Does God change his mind? Yes.

Does God change his mind? No.

And we let that paradox dance.

Musings on Openness Theology, Part 1: Is God Impassive?

We just finished up a study of John Sanders' book A God Who Risks: A Theology of Providence in our Wednesday night class at the Highland Church of Christ.

We just finished up a study of John Sanders' book A God Who Risks: A Theology of Providence in our Wednesday night class at the Highland Church of Christ.

Sanders' book is one of a few books out on the market that make the case for what is known as openness theology. The general contention of openness theology is that the future is "open," which is to say, contingent (as opposed to being fixed and predetermined by God).

By contrast, a great deal of theological thinking (notably Augustine and Calvin) has suggested that all past, present, and future events are determined, fixed, and known by God. In this view, the entire timeline of history exists, unalterable, before the eyes of God.

In this "closed" view the future is not "open" or contingent. By contingent I mean "if..., then...". In the closed view of the future there is no if/then. The future is what it is and God has known it for all eternity. There are obviously important nuances to be added here, but, to start, I'm painting in broad strokes. As a representative of this theological perspective Sanders quotes John Calvin:

"Nothing happens except what is knowingly and willingly decreed by God." Further, God "foresees future events only by reason of the fact that he decreed that they take place."

In contrast to this view, openness theology suggests that the future is open and contingent. The world unfolds in an if/then manner. If humans do X God will respond with Y leading to future Z. But if humans do X' then God will respond with Y' leading to future Z'. Given this contingency there is a whole (possibly infinite) set of futures--Z'', Z''', Z''', Z''''', Z'''''', and so on--that might come to be. It all depends upon human/divince interactions RIGHT NOW. Sanders quotes Richard Foster to represent this view:

"We have been taught that everything in the universe is already set, and so things cannot be changed. And if things cannot be changed, why pray? ... In fact, the Bible stresses so forcefully the openness of our universe that it speaks of God constantly changing his mind in accord with his unchanging love...We are working with God to change the future!"

The openness view of God is also called a relational view because human/divine relations are infused with spontaneity and portent. The if/then dynamic makes relational activities with God such as prayer pop and come alive. The future, literally, hangs in the balance.

But openness theology is wildly controversial as it seems to call for the revision of some classic theological commitments regarding the qualities of God. Specifically, God is considered to be (relevant to our discussion here) omnipotent, omniscience, and omnipresent. These adjectives are taken to describe the Transcendent Perfection of God.

The issue is, if God doesn't know the future (either because the future doesn't exist, a view known as presentism, or because God doesn't know which path the future will take) then isn't this a limitation on his omniscience? Can God not know something? Further, can a Perfect God change his mind or make a mistake?

Although these are interesting questions which I will return to, the big issue for me during the study was God's impassibility.

The doctrine of God's impassibility states that God does not experience emotions (as humans understand them). That is, God his "impassive" in the face of events. God is not surprised, alarmed, chagrined, amused, charmed, angered, happy, frustrated or saddened by events the way we humans are. God isn't, like us, affected by events. If God were affected by things then God isn't Transcendent and omnipotent. You can't "touch"--physically, causally, or emotionally--God.

This doctrine is simply the logical outcome of God's omnipresence, omniscience, and omnipotence. If God knows all things from the beginning of time then he can't properly be surprised by the outcome of events. True, the bible does suggest that God experiences emotions, even strong and violent emotions. And God even seems to regret some of his choices. But according to the adherents of divine impassibility all this is just metaphor and anthropomorphism. God doesn't have feelings. (God is love, of course, but this has more to do with his steadfast goodness, his hesed, than the feelings of human love. In fact, most churches downplay human love in favor of this vision of "God-like love." Love is a "commitment," a "choice," it isn't a feeling. Which is true to a point, but it's a crappy notion of love. Imagine me saying to my wife, "Baby, I love you. And by this I mean I'm choosing to stay committed to you." Very romantic.)

Openness theology, by contrast, claims that, because the future is open and contingent, God is passable, God does experience emotions. Those biblical passages speaking of God's anger, joy, longing, frustration, regret, and sorrow speak to something real which parallels the human experience of emotions.

So there is a tension. A tension between the Greek notion of God's immutable and unchanging Perfection. And a Hebrew notion of a psychologically complicated and emotional God. The bible hints at both.

So, I ask: Which is it?

Interdependency

Look round our world; behold the chain of love

Look round our world; behold the chain of love

Combining all below and all above.

See plastic Nature working to this end,

The single atoms each to other tend,

Attract, attracted to, the next in place,

Form'd and impell'd its neighbour to embrace.

See matter next, with various life endued,

Press to one centre still, the gen'ral good;

See dying vegetables life sustain,

See life dissolving vegetate again.

All forms that perish other forms supply

(By turns we catch the vital breath, and die),

Like bubbles on the sea of Matter borne,

They rise, they break, and to that sea return.

Nothing is foreign; parts relate to whole;

One all-extending, all-preserving, soul

Connects each being, greatest with the least;

Made beast in aid of man, and man of beast;

All serv'd all serving: nothing stands alone;

The chain holds on, and where it ends unknown.

Alexander Pope--selection from Essay on Man

Everything I Learned about Christmas I Learned from Watching TV, Final Installment: The True Meaning of Christmas

After the hints about Christmas from the Grinch and Rudolf I finally turned to that trusted friend Charlie Brown.

After the hints about Christmas from the Grinch and Rudolf I finally turned to that trusted friend Charlie Brown.

In A Charlie Brown Christmas Charlie Brown is struggling to find out why Christmas is so depressing. He seeks advice from his local psychiatrist, Lucy, who gets him to direct the school Christmas play.

Well, this doesn't go very well. Eventually, Charlie Brown is rejected as director and asked instead to go buy a Christmas tree for the play.

Most of the symbolism in A Charlie Brown Christmas focuses on the tree he picks out. Out of all the shiny, bright metallic trees (Which I never have understood, btw. Why are they selling hollow metallic trees? Was this ever a trend?) Charlie Brown picks a real but forlorn little tree that isn't much more than a branch.

Charlie Brown takes this "tree" back to the cast and they laugh at both him and the tree. This ridicule pushes Charlie Brown over the edge and he finally screams, "Would someone please tell me the true meaning of Christmas!!!!!" At which point Linus steps forward.

But before we hear Linus' answer, let's reflect on the symbol of the forlorn little Christmas tree. It's a humble little tree, not much to look at. And it's rejected and despised by men. And yet, it is real. All those flashy other trees are dead, cold, and fake. They are empty and hollow. But this fragile little tree is REAL. It's fragile, but real.

And all this taught me that whatever Christmas is about, it is about something that is humble, about something fragile and weak, about something that is despised, marginalized, and overlooked. It is life, it's real, but it's so humble that it is easily overlooked and passed over. Further, its humility makes it a stone of stumbling, a scandal, and a reason for offense.

So, to recap, these are all the lessons I learned about Christmas from watching TV:

I learned that Christmas was MORE and that it had something to do with finding community.But to this point in all this TV viewing no one ever connected the dots among all these things. No one had spoken the word that explained just what all this stuff had to do with Christmas. So I perfectly understood why Charlie Brown screamed "Isn't there anyone who knows what Christmas is all about!!!!!"

I learned that, because of Christmas, there were no more misfits, no more outsiders or marginalized ones.

I learned about empathy, compassion, and that Messiahs might be misfits.

I learned about how community can be the route for the redemption of evil.

And here with Charlie Brown, I learned that the humility of Christmas makes it oft overlooked and despised.

Well, Charlie Brown and I finally got our answer. Linus steps forward and explains it all:

May there be peace on earth and good will to all.

Everything I Learned about Christmas I Learned from Watching TV, Part 2: A Place for Misfits

After watching How the Grinch Stole Christmas l knew there was something special about Christmas. But How the Grinch Stole Christmas never says exactly why Christmas is special. I got a clue to answering this question by watching that classic Christmas program Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer.

After watching How the Grinch Stole Christmas l knew there was something special about Christmas. But How the Grinch Stole Christmas never says exactly why Christmas is special. I got a clue to answering this question by watching that classic Christmas program Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer.

The entire plot of Rudolf centers around misfits. The central misfits are Rudolf and the elf Hermey.

Rudolf, obviously, has some kind of genetic mutation. He's got a red nose and that, well, just isn't natural. So he is shunned, mocked, and excluded from the reindeer games.

Hermey has a different problem. He sucks at making toys. And he also doesn't enjoy singing in Santa's elf choir. What Hermey really wants to be is a dentist. But for this curious interest he is, like Rudolf, ostracized and made fun of. They are both, clearly, misfits. This is captured in the mournful little song they sing, "Why am I such a misfit?"

For these scenes and the song see here:

So Hermey and Rudolf leave Christmas Town set out on their own.

The misfit theme is continued when Hermey, Rudolf, and Yukon Cornelius, after being chased by The Abominable Snowman, find the Island of Misfit Toys. This is an island where rejected, unwanted, and unloved toys find sanctuary. Rudolf, sympathetic to the plight of the Misfit Toys, because Rudolf knows what it's like to be a misfit, promises to take their plight to Santa:

At this point in the show all the misfit themes are coming to a climax. We see misfits seeking community, we see empathy as one misfit identifies with another, and, finally, we see one misfit seeking to act as savior. A misfit to save the misfits. A misfit Messiah.

But the theology or Rudolf takes its most radical, surprising, and extreme turn when the personification of evil, The Abominable Snowman, comes back from death in a quirky resurrection event--Bumble's Bounce!--as a peaceable creature who is also in need of loving community. Apparently, this "evil" creature is also a misfit. And the hint is that he's "abominable" because he's been marginalized and without community. Many "evil" people might just be misfits, but twisted due to being isolated for way too long while stewing in their loneliness. Maybe if Rudolf, Hermey and all those misfit toys were left isolated for too long they would also, in the end, become "abominable."

So, summarizing all this, I learned from Rudolf this important lesson about Christmas: Something about Christmas means misfits have a place, a community, a home. Or, rephrased, Christmas means that there are no more misfits.

But I was still puzzled as a child. From How the Grinch Stole Christmas I learned that Christmas was more than presents and Christmas trees. And from Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer I learned that Christmas had something to do with misfits finding a place of love. But in both shows the reason behind it all remained elusive. Why do misfits have a home? And what does being a misfit have to do with Christmas? Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer never says.

So I was quite puzzled. But luckily, there was more TV to watch! And I finally got my answers in an speech delivered by a boy who loved to carry a blue blanket...