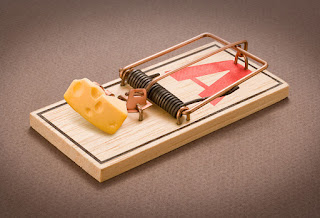

St. Augustine once compared the cross of Jesus to a mousetrap--crux muscipula diaboli.

"The cross is the devil's mousetrap."

This idea strikes modern Christians as alien and strange. Largely because we have lost the Christus Victor frame of the early church. For those new to this blog or these ideas, Christus Victor was the dominate view of the atonement for the first thousand years of the church. It is the view that the Incarnation, Crucifixion and Resurrection of Jesus was involved in liberating us from our captivity to sin, death, and the Devil.

Then as now, Christians tend to push past general formulations such as this--Christ rescues us from the Devil--to ask question about mechanisms. We move from "What happened?" to "How did it happen?" For example, modern Christians subscribing to penal substitutionary atonement often ask about the mechanisms at work in the theory: Why does God demand our death and how exactly does Jesus's death satisfy God's wrath and justice? In a similar way, the early Christians wondered about the mechanisms of Christus Victor: How exactly did Jesus liberate us from the power of the Devil?

These sorts of question lead us out onto thin ice. When we turn to stories about mechanisms--hypothetical scenarios about how it all works--we start to get specific about things that the bible only hints at. No doubt, for example, the bible suggests that there was a substitutionary facet to the death of Jesus. Something bad happened to him that should have or could have happened to us. But how, exactly, that substitution "worked" in saving us is hard to say as the bible doesn't get into specific mechanisms. In fact, most biblical scholars would say that substitution isn't really a mechanism, it's a metaphor. That what we have in the bible are a lot of metaphors without a lot of unpacking of those metaphors. Not being content with that what a lot Christians have done throughout the ages is to lock onto one particular metaphor and then unpack the hell out of it. Specifying in great and specific detail how this one particular metaphor might literally and mechanistically "work." These attempts are sort of like reading a great poem and then insisting in your English term paper that this is what the poem literally means. That's fine if you are a 5th grader, but we expect more from adult readers of poetry. And Scripture.

Still, we thirst for mechanisms. We like to get specific. We crave cause and effect stories. And so, in unpacking the Christus Victor metaphors of ransom and liberation in the bible, Augustine posited a mechanism. How did the cross save us from the Devil? The cross, he suggested, is like a mousetrap.

How so?

The idea goes like this as unpacked by various church fathers. From the beginning of Jesus's ministry Satan tries to thwart Jesus. But failing to get Jesus to fall into sin Satan ultimately decides to kill Jesus, to just get rid of the guy. (Recall that Satan enters Judas's heart suggesting that the death of Jesus is Satan's idea and plan.) Satan, we know, eventually succeeds and Jesus is killed. Thus, Satan, who possesses the keys to Death and Hades, now "owns" Jesus and has him locked up in Hades.

Satan has taken the cheese.

Because what Satan doesn't know is that Jesus isn't just another human being. Jesus is God Incarnate. In this Jesus is sort of like a Trojan Horse. So when Satan takes Jesus to Hades--Surprise!--he finds that the enemy has entered the gates. There in hell Jesus takes the keys of Death and Hades from Satan, binds him, and then releases the captives. In Christian theology this is called the Harrowing of Hell.

The mousetrap snaps.

Modern Christians tend to find this whole scenario pretty weird and implausible. I agree. But I just love this story. I find it way more interesting and theologically rich than penal substitutionary atonement.

Here are two reasons why I like the mousetrap story.

First, I think it is a recurring theme in the New Testament, and in the gospels in particular, that the Kingdom of God is hidden. And why is it hidden? Because it is small, weak, and powerless. The Kingdom of Heaven is in our midst. But the Kingdom of Heaven is like a mustard seed--too small for us to see or notice. Like the homeless Lazarus at the rich man's gate. Or the child standing off to the side while the adults are talking. Or the slave who is washing your feet. The Kingdom of God is in all these places. But we can't see it.

Thus it is not surprising that those without the eyes to see it will miss the Kingdom and will fail to appreciate its logic and power. In the words of St. Paul, the cross will always be foolishness to the world. Satan cannot see the power of God in the cross. And most of us can't either.

Second, the mousetrap story suggests that evil, in its exercise of power, will overreach. God, by contrast, by allowing evil to overreach, saves us non-violently, with powerlessness. God is passive, allowing Satan to kill, allowing Satan to use power and violence to accomplish the purposes of evil. On the surface, God becomes the mouse, the dead thing caught in the trap, the one hanging on the cross. God absorbs violence and overcomes it with love. What looks like a dead mouse to the eyes of the world--Jesus hanging on the cross--is actually the power and Kingdom of God. In the biblical imagination, Jesus is enthroned on the cross.

The dead mouse is actually the mousetrap.

Sometimes I wonder if this is why God doesn't use power in this world. If this is why God doesn't come down and start knocking heads together. I wonder what that sort of God would look like. Like Satan?

But maybe God is powerfully at work in the world, but in the hidden, powerless way Jesus described in his Kingdom parables. Maybe, as St. Paul said, God is using the powerless and weak things of the world to shame and defeat the powerful.

Maybe there are mousetraps all around us.

Email Subscription on Substack

Richard Beck

Welcome to the blog of Richard Beck, author and professor of psychology at Abilene Christian University (beckr@acu.edu).

Welcome to the blog of Richard Beck, author and professor of psychology at Abilene Christian University (beckr@acu.edu).

The Theology of Faërie

The Little Way of St. Thérèse of Lisieux

The William Stringfellow Project (Ongoing)

Autobiographical Posts

- On Discoveries in Used Bookstores

- Two Brothers and Texas Rangers

- Visiting and Evolving in Monkey Town

- Roller Derby Girls

- A Life With Bibles

- Wearing a Crucifix

- Morning Prayer at San Buenaventura Mission

- The Halo of Overalls

- Less

- The Farmer's Market

- Subversion and Shame: I Like the Color Pink

- The Bureaucrat

- Uncle Richard, Vampire Hunter

- Palm Sunday with the Orthodox

- On Maps and Marital Spats

- Get on a Bike...and Go Slow

- Buying a Bible

- Memento Mori

- We Weren't as Good as the Muppets

- Uncle Richard and the Shark

- Growing Up Catholic

- Ghostbusting (Part 1)

- Ghostbusting (Part 2)

- My Eschatological Dog

- Tex Mex and Depression Era Cuisine

- Aliens at Roswell

On the Principalities and Powers

- Christ and the Powers

- Why I Talk about the Devil So Much

- The Preferential Option for the Poor

- The Political Theology of Les Misérables

- Good Enough

- On Anarchism and A**holes

- Christian Anarchism

- A Restless Patriotism

- Wink on Exorcism

- Images of God Against Empire

- A Boredom Revolution

- The Medal of St. Benedict

- Exorcisms are about Economics

- "Scooby-Doo, Where Are You?"

- "A Home for Demons...and the Merchants Weep"

- Tales of the Demonic

- The Ethic of Death: The Policies and Procedures Manual

- "All That Are Here Are Humans"

- Ears of Stone

- The War Prayer

- Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Experimental Theology

- Eucharistic Identity

- Tzimtzum, Cruciformity and Theodicy

- Holiness Among Depraved Christians: Paul's New Form of Moral Flourishing

- Empathic Open Theism

- The Victim Needs No Conversion

- The Hormonal God

- Covenantal Substitutionary Atonement

- The Satanic Church

- Mousetrap

- Easter Shouldn't Be Good News

- The Gospel According to Lady Gaga

- Your God is Too Big

From the Prison Bible Study

- The Philosopher

- God's Unconditional Love

- There is a Balm in Gilead

- In Prison With Ann Voskamp

- To Make the Love of God Credible

- Piss Christ in Prison

- Advent: A Prison Story

- Faithful in Little Things

- The Prayer of Jabez

- The Prayer of Willy Brown

- Those Old Time Gospel Songs

- I'll Fly Away

- Singing and Resistence

- Where the Gospel Matters

- Monday Night Bible Study (A Poem)

- Living in Babylon: Reading Revelation in Prison

- Reading the Beatitudes in Prision

- John 13: A Story from the Prision Study

- The Word

Series/Essays Based on my Research

The Theology of Calvin and Hobbes

The Theology of Peanuts

The Snake Handling Churches of Appalachia

Eccentric Christianity

- Part 1: A Peculiar People

- Part 2: The Eccentric God, Transcendence and the Prophetic Imagination

- Part 3: Welcoming God in the Stranger

- Part 4: Enchantment, the Porous Self and the Spirit

- Part 5: Doubt, Gratitude and an Eccentric Faith

- Part 6: The Eccentric Economy of Love

- Part 7: The Eccentric Kingdom

The Fuller Integration Lectures

Blogging about the Bible

- Unicorns in the Bible

- "Let My People Go!": On Worship, Work and Laziness

- The True Troubler

- Stumbling At Just One Point

- The Faith of Demons

- The Lord Saw That She Was Not Loved

- The Subversion of the Creator God

- Hell On Earth: The Church as the Baptism of Fire and the Holy Spirit

- The Things That Make for Peace

- The Lord of the Flies

- On Preterism, the Second Coming and Hell

- Commitment and Violence: A Reading of the Akedah

- Gain Versus Gift in Ecclesiastes

- Redemption and the Goel

- The Psalms as Liberation Theology

- Control Your Vessel

- Circumcised Ears

- Forgive Us Our Trespasses

- Doing Beautiful Things

- The Most Remarkable Sequence in the Bible

- Targeting the Dove Sellers

- Christus Victor in Galatians

- Devoted to Destruction: Reading Cherem Non-Violently

- The Triumph of the Cross

- The Threshing Floor of Araunah

- Hold Others Above Yourself

- Blessed are the Tricksters

- Adam's First Wife

- I Am a Worm

- Christus Victor in the Lord's Prayer

- Let Them Both Grow Together

- Repent

- Here I Am

- Becoming the Jubilee

- Sermon on the Mount: Study Guide

- Treat Them as a Pagan or Tax Collector

- Going Outside the Camp

- Welcoming Children

- The Song of Lamech and the Song of the Lamb

- The Nephilim

- Shaming Jesus

- Pseudepigrapha and the Christian Witness

- The Exclusion and Inclusion of Eunuchs

- The Second Moses

- The New Manna

- Salvation in the First Sermons of the Church

- "A Bloody Husband"

- Song of the Vineyard

Bonhoeffer's Letters from Prision

Civil Rights History and Race Relations

- The Gospel According to Ta-Nehisi Coates (Six Part Series)

- Bus Ride to Justice: Toward Racial Reconciliation in the Churches of Christ

- Black Heroism and White Sympathy: A Reflection on the Charleston Shooting

- Selma 50th Anniversary

- More Than Three Minutes

- The Passion of White America

- Remembering James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman

- Will Campbell

- Sitting in the Pews of Ebeneser Baptist Church

- MLK Bedtime Prayer

- Freedom Rider

- Mountiantop

- Freedom Summer

- Civil Rights Family Trip 1: Memphis

- Civil Rights Family Trip 2: Atlanta

- Civil Rights Family Trip 3: Birmingham

- Civil Rights Family Trip 4: Selma

- Civil Rights Family Trip 5: Montgomery

Hip Christianity

The Charism of the Charismatics

Would Jesus Break a Window?: The Hermeneutics of the Temple Action

Being Church

- Instead of a Coffee Shop How About a Laundromat?

- A Million Boring Little Things

- A Prayer for ISIS

- "The People At Our Church Die A Lot"

- The Angel of Freedom

- Washing Dishes at Freedom Fellowship

- Where David Plays the Tambourine

- On Interruptibility

- Mattering

- This Ritual of Hallowing

- Faith as Honoring

- The Beautiful

- The Sensory Boundary

- The Missional and Apostolic Nature of Holiness

- Open Commuion: Warning!

- The Impurity of Love

- A Community Called Forgiveness

- Love is the Allocation of Our Dying

- Freedom Fellowship

- Wednesday Night Church

- The Hands of Christ

- Barbara, Stanley and Andrea: Thoughts on Love, Training and Social Psychology

- Gerald's Gift

- Wiping the Blood Away

- This Morning Jesus Put On Dark Sunglasses

- The Only Way I Know How to Save the World

- Renunciation

- The Reason We Gather

- Anointing With Oil

- Incarnations of God's Mercy

Exploring Preterism

Scripture and Discernment

- Owning Your Protestantism: We Follow Our Conscience, Not the Bible

- Emotional Intelligence and Sola Scriptura

- Songbooks vs. the Psalms

- Biblical as Sociological Stress Test

- Cookie Cutting the Bible: A Case Study

- Pawn to King 4

- Allowing God to Rage

- Poetry of a Murderer

- On Christian Communion: Killing vs. Sexuality

- Heretics and Disagreement

- Atonement: A Primer

- "The Bible says..."

- The "Yes, but..." Church

- Human Experience and the Bible

- Discernment, Part 1

- Discernment, Part 2

- Rabbinic Hedges

- Fuzzy Logic

Interacting with Good Books

- Christian Political Witness

- The Road

- Powers and Submissions

- City of God

- Playing God

- Torture and Eucharist

- How Much is Enough?

- From Willow Creek to Sacred Heart

- The Catonsville Nine

- Daring Greatly

- On Job (Gutiérrez)

- The Selfless Way of Christ

- World Upside Down

- Are Christians Hate-Filled Hypocrites?

- Christ and Horrors

- The King Jesus Gospel

- Insurrection

- The Bible Made Impossible

- The Deliverance of God

- To Change the World

- Sexuality and the Christian Body

- I Told Me So

- The Teaching of the Twelve

- Evolving in Monkey Town

- Saved from Sacrifice: A Series

- Darwin's Sacred Cause

- Outliers

- A Secular Age

- The God Who Risks

Moral Psychology

- The Dark Spell the Devil Casts: Refugees and Our Slavery to the Fear of Death

- Philia Over Phobia

- Elizabeth Smart and the Psychology of the Christian Purity Culture

- On Love and the Yuck Factor

- Ethnocentrism and Politics

- Flies, Attention and Morality

- The Banality of Evil

- The Ovens at Buchenwald

- Violence and Traffic Lights

- Defending Individualism

- Guilt and Atonement

- The Varieties of Love and Hate

- The Wicked

- Moral Foundations

- Primum non nocere

- The Moral Emotions

- The Moral Circle, Part 1

- The Moral Circle, Part 2

- Taboo Psychology

- The Morality of Mentality

- Moral Conviction

- Infrahumanization

- Holiness and Moral Grammars

The Purity Psychology of Progressive Christianity

The Theology of Everyday Life

- Self-Esteem Through Shaming

- Let Us Be the Heart Of the Church Rather Than the Amygdala

- Online Debates and Stages of Change

- The Devil on a Wiffle Ball Field

- Incarnational Theology and Mental Illness

- Social Media as Sacrament

- The Impossibility of Calvinistic Psychotherapy

- Hating Pixels

- Dress, Divinity and Dumbfounding

- The Kingdom of God Will Not Be Tweeted

- Tattoos

- The Ethics of :-)

- On Snobbery

- Jokes

- Hypocrisy

- Everything I learned about life I learned coaching tee-ball

- Gossip, Part 1: The Food of the Brain

- Gossip, Part 2: Evolutionary Stable Strategies

- Gossip, Part 3: The Pay it Forward World

- Human Nature

- Welcome

- On Humility

Jesus, You're Making Me Tired: Scarcity and Spiritual Formation

A Progressive Vision of the Benedict Option

George MacDonald

Jesus & the Jolly Roger: The Kingdom of God is Like a Pirate

Alone, Suburban & Sorted

The Theology of Monsters

The Theology of Ugly

Orthodox Iconography

Musings On Faith, Belief, and Doubt

- The Meanings Only Faith Can Reveal

- Pragmatism and Progressive Christianity

- Doubt and Cognitive Rumination

- A/theism and the Transcendent

- Kingdom A/theism

- The Ontological Argument

- Cheap Praise and Costly Praise

- god

- Wired to Suffer

- A New Apologetics

- Orthodox Alexithymia

- High and Low: The Psalms and Suffering

- The Buddhist Phase

- Skilled Christianity

- The Two Families of God

- The Bait and Switch of Contemporary Christianity

- Theodicy and No Country for Old Men

- Doubt: A Diagnosis

- Faith and Modernity

- Faith after "The Cognitive Turn"

- Salvation

- The Gifts of Doubt

- A Beautiful Life

- Is Santa Claus Real?

- The Feeling of Knowing

- Practicing Christianity

- In Praise of Doubt

- Skepticism and Conviction

- Pragmatic Belief

- N-Order Complaint and Need for Cognition

Holiday Musings

- Everything I Learned about Christmas I Learned from TV

- Advent: Learning to Wait

- A Christmas Carol as Resistance Literature: Part 1

- A Christmas Carol as Resistance Literature: Part 2

- It's Still Christmas

- Easter Shouldn't Be Good News

- The Deeper Magic: A Good Friday Meditation

- Palm Sunday with the Orthodox

- Growing Up Catholic: A Lenten Meditation

- The Liturgical Year for Dummies

- "Watching Their Flocks at Night": An Advent Meditation

- Pentecost and Babel

- Epiphany

- Ambivalence about Lent

- On Easter and Astronomy

- Sex Sandals and Advent

- Freud and Valentine's Day

- Existentialism and Halloween

- Halloween Redux: Talking with the Dead

The Offbeat

- Batman and the Joker

- The Theology of Ugly Dolls

- Jesus Would Be a Hufflepuff

- The Moral Example of Captain Jack Sparrow

- Weddings Real, Imagined and Yet to Come

- Michelangelo and Neuroanatomy

- Believing in Bigfoot

- The Kingdom of God as Improv and Flash Mob

- 2012 and the End of the World

- The Polar Express and the Uncanny Valley

- Why the Anti-Christ Is an Idiot

- On Harry Potter and Vampire Movies

Quite an inspiring post, as always. By the way, do you know where Augustine says that?

Best

"Satan doesn't know is that Jesus isn't just another human being. Jesus is God Incarnate."

In actuality Satan knew Jesus was God's Son and was seeking to steal the inheritance due Jesus

Secondly, if God were powerless, we would all be destroyed by Satan, He hates mankind, the only power he has is what is given to him by God

Interesting side note: The concept of the cross as the Devil's Mousetrap comes up in art from time to time - most notably, perhaps, in the Merode Altarpiece of the 1420s. The Dutch painters of the period often suffused their work with symbolic meaning, and in the right-hand panel of the triptych you can see Joseph, who is depicted as making mousetraps, for the aforementioned reasons. Here's a link to the Wikipedia article on the Altarpiece, so you can have a look:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C3%A9rode_Altarpiece

Thanks -- this is a really helpful (simple, clear) illustration of Christus Victor atonement theory. Maybe our obsession with the details of "how it happened" is itself a mousetrap? I immediately thought of the newfangled sticky mousetraps that don't immediately kill, but rather keep the poor, unfortunate creature immobilized on the trap to either starve, freeze, or be either released or put out of its misery by the trap-setter.

The PSA theory, in the systematic scheme of things, generates more cognitive dissonance for me than assurance of salvation. As long as a person is stuck in a "soterian gospel" mindset, he/she cannot so easily deviate from PSA. The house of cards -- the mechanism of "how" (a/k/a systematic theology) -- comes tumbling down if the PSA card is disturbed. And, surrounding that issue is the belief that holding to a particular set of beliefs with absolute certainty is the mechanism that saves. Problematic! It took me a long time to step back, gain some perspective on my own thinking, and understand why I had been so stuck in that thinking.

And, oh, on the literary depth of the Bible -- "a lot of metaphors without a lot of unpacking of those metaphors:" Among my Christian friends, one group with whom I am fairly involved takes a literal, inerrant view of the Bible, while the other group seems to see more harm than good in even reading the Bible! This I find highly ironic, especially given that I have specifically chosen to join both of these groups. In the first group, I have been called a flaming liberal (theologically and politically), and I suspect that the second group views me as strongly conservative (theologically, at least, though no one has said it because they are too polite/tolerant to say it). In both cases, I speak honestly about what I believe and *think* I know. ;-) When I put all this together, I realize how subjective labels are. Further, that I must, in fact, be much more moderate than even I had thought of myself. :-D

Finally (I apologize for the comment length), when you suggest that God at work doesn't appear the way man assumes that power will manifest, this resonates with some thoughts I've been having on Christian witness as "movement." We so want to see BIG results and drastic, sudden changes. If history is any indicator, I don't think we will see God moving in such dramatically apparent ways. I think we can see God already at work in ways, paradoxically, big and small. Take the Prison Bible Fellowship and Freedom Church. If you are a witness to it (with "spiritual" eyes to see), it is HUGE. From the world's point of view, few have probably taken notice or been impressed by the miracles taking place. And that is why it is so important that we keep telling (and retelling) our stories in a way that makes us braver. I think of Christus Victor as the denouement of the Grand Narrative that enlivens and redeems all of our stories with love and hope. I just love this story, too! ~Peace~

"These attempts are sort of like reading a great poem and then insisting in your English term paper that this is what the poem literally means. That's fine if you are a 5th grader, but we expect more from adult readers of poetry. And Scripture."

This is what most people do with the Bible -- read it and then explain it. And it always sounds to me just like the myths of old. Things that people would do, acting in four-dimensional space and time. Human motives and activities imputed to a Deity, explained in other-worldly terms and patterns we already recognize. Because we have no other reference for the metaphysical. It is outside our experience, and all we can do is look into the night sky and imagine. Looking for mechanisms via science or religion.

I like your take on the metaphor. I like visiting the metaphysical realm. But we can never know if any of this is "true" until after we are dead.

Brilliant and succinct. PSA is, without a doubt, the stickiest theological mechanistic mousetrap, and like Susan says, it's immobilizing. When I was in it, there was no sense of the glorious freedom in Christ that it advertises. None. Just fears of not getting it exactly right, and all my friends and loved ones going to hell. With Christus Victor, I get a sense that God loved us enough to take on the whole enchilada in Christ, so we can really live without anxiety toward God.

One place where Augustine uses this metaphor is Sermon 80 where he says: "And what did our redeemer do to him who held us captive? For our ransom he held out His Cross as a trap; he placed in It as a bait His Blood."

That's what I love about Christus Victor theology. God's movement toward us is wholly benevolent.

We can't seem to resist what I call "filling in the white space" between biblical affirmations, metaphors, and images. Classic is the way we deal with divine sovereignty and human freedom. Scripture teaches both, teaches that God's will will prevail, and that this should make us grateful and courageous in following Jesus. We've filled in the "white spaces" with our answers to the "how" questions, fought with each other and even created new denominations over how we fill in this "white space" and done little to advance the gospel.

I like this a lot!

But another aspect that's charming me in your writing this, is that yesterday as I was thinking about ambiguity and paradox as drivers of mathematics via William Byers, this thought hit me:

What if the more theistic god was in our world, the less human we would be able to be?

I think this question coincides with yours about why god isn't just knocking heads together. It also points to a possibility that to be human--to participate in real and full humanness--is something bigger than we typically think.

You don't have a problem with Satan as the conscious, active, deliberate agent of Evil, who lays plots and takes concrete steps in executing them? If that's true, it isn't at all clear to me that Jesus has actually liberated us from Satan's power, except in the soterian sense ... "I'll fly away!" But "God so loved the world".

Matthew 8:29, Mark 1:24, Mark 3:11, Luke 4:4, Luke 4:34, Luke 8:28.

Satan was pretty thick if he thought he could hold the Son of God in Hell. Which is a bit naff, because though we might not want God to come down here and start messing with us - why can't He just, you know, duff up the stupid evil guy whose been leading us in circles all this time. Oh - ok: "I wonder what that sort of God would look like. Like Satan?" - because He'd be like Satan. I get that. But why doesn't He unleash the power of Love on Satan then? Isn't the logical, and troubling implication of relying solely on Christus Victor that there are created beings wholly unable to respond to that "weak" Love. You say: "Satan cannot see the power of God in the cross." Is that his fault? Or is that how God made him? Are there people too, who are literally unable to respond to or recognise the cross for what it is? Is that their fault or God's? Is it a position of choice or of nature?

If we assume you're right and Satan simply can't understand Love, and continues to be behind/exhort/tempt others to commit evil, then one has to ask where will it end? Might it end when Satan reaches the same conclusion that Christians do? But this seems strange - Satan and his minions appear, in Scripture, to have had a more immediate grasp of God's identity than some of His closest followers. But if Satan will never be able to grasp that Love, where will it end? Never? If we think that, then the nature of God's Love as described by Christus Victor has limits - it might take a bit to reach them, but limits nonetheless. Or will Satan's evil end when God *does* something about it? When God puts and end to him. When God uses *forces* Satan and his followers to desist.

We'd probably all agree that it isn't justice to punish someone for something that you have caused to exist. If we assume that Satan can't understand Love, but that a good God would nevertheless want to bring about a permanent end to his shenanigans, then only possibility remains: Satan is responsible (culpable) for his evil, and that God would be perfectly *justified* in bringing him to account. But if that's so, He'd be justified in bringing anyone who willingly caused evil to account. The question for those of us who have done evil becomes quite a clear one: do we want to get judged with Satan, or do we want to get judged with Christ on the Cross?

Whilst I like Christus Victor for its capacity to explain the triumph of the love of God (the penultimate paragraph, I'd agree with absolutely), it seems to be a false divide to say that God could not use the weak and small things to bring justice too. Justice is essential to an understanding of the Cross. Because without it, we get a picture of God's love as something limited, or worse, that evil will continue simply because God - the one being both fully justified in and capable of ending evil permanently - is unwilling to use force. That even goes some way towards the heresy that evil is a necessary component of existence.

Fortunately, God's Love is not limited. And nor is His justice. The two meet in perfect unison in the Cross, and in the Person of Christ: the Lion and the Lamb, the Prince of Peace and the Eternal Judge. Really, when we look at how Christ is described, this shouldn't be a surprise to us, or even a difficulty.

I like the way this guy says it best:

http://thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/tgc/2011/11/01/rapping-the-attributes-of-god/

Augustine, Sermon 263, "On the Ascension of God"

Thanks Richard :-)

2012/5/14 Disqus

It's not that he is thick, it's always been about pride

I like this quite a lot.

I've been reading the Daodejing lately; I've found that some of it very much accords with the Psalms, the Gospels, and the Prophets, and I've found that some of it very much departs from them. (This is often within the same section.) DEO 17 reads, "If a wholly Great One rules / the people hardly know that he exists. / Lesser men are loved and praised, / still lesser ones are feared, / still lesser ones are despised." Now, I'm not entirely sure about all of this--in particular, I'm not sure that love is less than invisibility, which seems to be the case in DAO 17--but I was wondering if there was a way of thinking about God's hands-off approach in these terms: a good ruler acts in such a way that the subjects do not know they are being ruled. Reading this post, a second thought has come to me: Satan has a poor sense of what good power is, and so Satan "overreaches" and sits on the lower end of this spectrum, thinking that fear and hatred are the signs of a strong ruler.

I think that's a good point that I was thinking about as well. Satan knew Jesus was the Son of God, I mean, Jesus' temptation in the desert at the very least gives a hint that Satan knew that this man was different, right?

Thanks, Susan. As always, your additions help to unpack Richards work. I resonate with your sentence "We so want to see BIG results and drastic, sudden changes." It bothers me. A lot. So I think I end up going further than you, but here's some of my reasoning (which the mousetrap metaphor hints at so elegantly as Richard points out). We just want results on our terms. We want things to be tangible, visible, to see the fruits of our labor. I get that, but when we are immersed in a culture that lauds what is visible, and have a cultural and ecumenical track record (at least within the last 50 or so years) of measuring and quantifying everything, it's a bigger issue. I could probably write a book about it (maybe I will!). I think it must be a lingering symptom of the business model of churching. If we are honest, we want change on our own terms. It takes real submission to, and trust in God to let go of control of something and let God work or just stop controlling it. That's incredibly difficult because we don't get to own the change or look back and say, look what I did! It's also a subtle power play, I think. But that's very postmodern of me.

I think Richard is spot on with his assessment "Sometimes I wonder if this is why God doesn't use power in this world. If this is why God doesn't come down and start knocking heads together. I wonder what that sort of God would look like. Like Satan?" Too often the church looks more like Satan, running around trying to have its way with the world, to form people and communities "for their own good" in a predetermined "God-ordained" picture of who they are supposed to be and how things are supposed to go.

I haven't quite figured out how to walk that narrow line between engagement/influence and respecting the choices others make (I mean really respecting their choices, i.e. not judging them for those choices and making my judgment known to guilt/shame them into making better choices). I do think that the concept of "remaining with" a person or a community no matter what (or at least as much as we can) is one aspect towards a way forward.

I'm probably pretty naive, but I just don't get all the hubub surrounding PSA. Is it what certain groups do to it, what they make of it? I never really had a problem with it, and like Richard said in this piece, it is at least hinted at in Scripture. Is there a certain theology or tradition wrapped up in PSA?

Don't think I'm being defensive at all. I have no horses in this race. I'm just trying to understand where you, and many others, are coming from. Talk to me!

The better reference is the one ES Blofeld gives. Sermon 263.

Hi Stephen, I'm not taking you as defensive at all, and I'm glad to share with you where I've come from, and why getting out of it is a big deal to me. I was raised Southern Baptist, which is pretty fundamentalist theologically, and my family of origin certainly lived out some of the harsh aspects of that fundamentalism, which can be pretty negating and abusive. PSA emphasizes repeatedly and overtly how sinful and thus worthless in the eyes of God we "truly" are. How we deserve hell in infinitude for our sins, and how powerless we are in the grip in sin. How undeserving we are of God's love and grace and salvation. This is the primary message of PSA, the "bad news" as it were, that is supposed to be solved by "the good news/gospel." Looking at the cross, you're supposed to see "what you deserve." And the threat of hell looms large if you don't have "correct" belief and faith based on those correct beliefs, (which you won't even be capable of having if you're not among the "elect" anyway, so anyway you cut it, you can be screwed). Such "faith" is actually faith in a systematic mechanism designed to address how Jesus death in substitution (more so than his resurrection, which is almost an afterthought) bridges the sin gap between a wrathful God and us stupid, sinful humans. And even though this "God" loves us, he's gotta punish us with eternity in flames if we don't get it right.

Imagine being raised in that from childhood, being told how very worthless and sinful you are, and that's where I come from. God is "love," but this love is pretty abusive, dismissive of anything you can say or do, and by God you better be grateful for the many "blessings" you DO have (remember the starving children in China?). So "how dare you complain about anything when you have 'so much'". It can leave you pretty voiceless.

Thanks Patricia. I can definitely see those things at work. I still don't see the problem with PSA itself. Most definitely with how it is presented, though. Obviously it has been used and abused to the detriment of many, but I've seen it as an integral part of the story of Christ and what He has done for us. I've also enjoyed the work Richard has done to bring Christus Victor back on the mental map for us.

PSA and Christus Victor, for me, work in harmony with one another and I see both as being biblically-based. Kind of like Calvinism and Arminianism. You'd have to deny a part of the story as it is told in order to deny either one as legitimate. Now we don't have to like the terrible things that are done in the name of Christ, but we don't have to like the terrible things done in the name of Calvinism or PSA either.

It may be easier for me to have a different perspective because it didn't haunt my childhood like it has for so many others.

My opening remark was admittedly facecious. Those references are to spirits responding to Jesus and openly recognising Him as the Son of God. In that sense, the suggestion that Satan didn't know what he was getting himself into with the Cross is questionable: not only did the spirits know Him, but they understood His power and feared they would be destroyed by Christ: ""What do you want with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are - the Holy One of God!"" (Mark 1:24). Frankly, if demons could understand that God does not tolerate evil, it baffles me how Christians can struggle with it.

I suppose the response I might expect (on the basis of the theology laid out above) would be: "of course, but demons can't understand God's plan, they can only think in terms of destruction."

Except that it wasn't just the demons who understood the total eradication of evil was an essential part of God's plan: " “As the weeds are pulled up and burned in the fire, so it will be at the end of the age. The Son of Man will send out his angels, and they will weed out of his kingdom everything that causes sin and all who do evil." (Matthew 13:40-41).It's not a dichotomy between a simplistic mechanistic understanding of the Cross and a metaphorically-sensitive reading that would make your Literary Studies Professor proud, it's about the Eternal Truth. Jesus made it rather explicit that although He taught in parables, there was an "objective" Truth to be had. In fact, the Mark version puts it in a rather curious way, that rather than the disciples (poor illiterate fishermen - remember, who would probably be outmatched by that 5th Grader) being able to "unpack" Christ's parables in a nuanced fashion, instead 'for those outside everything is in parables' (Mark 4:11). In the context of the wider focus on the pharisees in that chapter, there's a definite sense too that those who are "on the outside" are making it too hard for themselves, or rather that they end up seeing only the metaphor rather than the higher Truth.

I just wonder why, if we should be wary about reading things too literal-mindedly, too mechanistically; we should be willing to embrace a theology, which by numerous people's admissions in this comments, neatly sidesteps having to deal with the difficulty of the plain descriptions, metaphors, and prophecies regarding God's abohorrence for evil, and His Will to deal with it decisively. Forcefully, even.

There are too many direct and unambiguous references, including many attributed directly to Jesus, of the place of God's judgement to dismiss all possibility of it because it clashes with a feeling that a good God wouldn't demand accountability or justice. If Christus Victor suggested a way of reconciling God's justice with its admiral presentation of the power of His love, it would be convicing over and above all the others - but it doesn't, and so can't be the whole picture. Even if that makes us all a bit uncomfortable.

It is very difficult to read any allegory without at least blurring the line between the allegorical and the literal meaning. It would appear that the Satan (borrowed from surrounding cultures, and placed in the heavenly court) was a way of unpacking the reality of suffering in the world and the relationship between suffering and sin. By the Second Temple times, heavily influenced by the dualism of Zoroastrianism (from Persian exile) and Platonism (Hellenistic expansion), the Diabolos personifies all that is against God. Christus Victor works within this same deep dualistic mythos.

No doubt, for many people over the centuries, the reality of evil in their lives has led them to interpret these deep mythological entities as literal. I tend to think we need to be able to hold on to the deep meaning while allowing the surface meanings to remain mythological. The church is not served by the continuation of this deep symbolism without intelligent unpacking. Richard does a great job in unpacking the literal in a way that draws the deep meaning into the fore.

Thanks, Stephen. I think you have made some excellent points. As I thought about this a bit more yesterday, it occurred to me that, at an individual level, our need to control the outcome may be more rooted in insecurity than in lust for power. Faith being what it is (believing, trusting, hoping in what we cannot see), I think we are often looking for confirmation that what we believe is real...that we're doing the right thing...that we're *right*. Maybe it's just me, though. Like Patricia, that early indoctrination is very difficult to shake. The "Real or Not Real" game (Mockingjay) struck a chord with me in that sense.

Insofar as individuals get sucked into unhealthy churches which have sold out to Satanic power plays, we too become pawns with a horse in the race, so to speak. Church as "business" -- I don't even know what to say about this anymore. As an introvert, I'm not impressed with such contrivances that flow from a business model of church. To say the least.

Stephen, I think we all struggle to be more loving and less judgmental. I think we all judge (even if we give it a prettier name such as "discern"). You've read Unclean, right? When we understand why we think and behave a certain way, and what pushes our buttons and why, the focus of judgment is on ourselves. And I don't know about you, but if I examine my own thoughts and actions carefully enough, I lose confidence for condemning anyone else. Humility allows me to respond with compassion and gentleness. Deep down, when a relationship has broken down, and/or I have chosen to part ways with a person or community, I have eventually gotten to the bottom of my grief, which is the limits of my love to "save" or, at the very least, "bear with" the other. The bitter truth is that there *are* limits to my love and what it can do to overcome or endure a bad situation. If this isn't enough to confirm our need for God and His grace, I don't know what would! As I experience that grace, I think I'm enabled to let that grace flow toward others. I don't think I can manufacture it on my own. In the words of Anne Lamott, "Helpmehelpmehelpmehelpmehelpme! Amen." ~Peace, brother. Thanks for this thoughtful interaction.

Stephen, a succinct "object lesson" video by an Orthodox guy who used to be from the church of Christ on the difference between PSA and CV is here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WosgwLekgn8&feature=player_embedded

I think one of the difficulties of PSA is its extreme unbalance. The focus on God's wrath and hatred aimed at mankind, who, unless you're one of the lucky "elect" are merely mantrash destined for the furnace. Please understand, I am in no way saying sin is okay, but sin is not the only aspect of being human, nor does it negate man's value in God's eyes, anymore than a child's doing wrong should get him disowned by his own father. Disciplined, yes; executed, no. Jesus' message to sinners, and John's before him, was to repent and turn from sin. To an offended brother, go show him his fault and give him a chance to make it right, if he will, with reconciliation being the objective. Jesus illustrated His Father in the prodigal son story, not as firebrand Zeus throwing lightening bolts in anger. And the worst offenders in Jesus' interactions were the religiously powerful, who set themselves up as judges of others' sins while downplaying their own, as with the woman caught in adultery. In denominations where PSA dominates, you see a lot of leadership emulating those religious leaders and not Christ. And if one happens to be female, then you're the genetic historical root cause of all evil, which is used to justify a whole lot of other garbage.

Hi Steve, thanks! I'm not very knowledgeable on the full doctrine or traditions of Orthodox Christianity, but this video lesson was beautiful. :-) ~Peace~

Not sure if it has been mentioned already...but as i read this post I was reminded of the Lewis' The Lion, Witch, and Wardrobe". Aslan springs the mousetrap on the Queen, as it were.

I don't see where we as Christians have lost the "Christus Victor" frame at all, nor do I see where it represents any sort of genuine contrast from the ""substitutionary atonement" model of the cross. The good news of the gospel encompasses both aspects equally and I have heard both preached well all my life.

I ran across your series on Demonology (while pursuing a seemingly unrelated query about Walter Wink, curiously). So we are talking existentially rather than literally. I'm entirely OK with demons as a way of speaking about emergent phenomena associated with institutions ... even Richard Dawkins "believes in" something similar he called "memes". But on this view I'm not sure how "Hell was harrowed". The passion doesn't seem to have harmed the Temple noticeably, let alone Rome. Or do you mean that otherwise, Jesus would be known to us as only one more minor prophet and there would be no Christianity? But again as you say, the Powers have no problem subverting the Churches.

It seems the thing is not so much what Jesus did as what He showed us to do, which is not to fear death. Or rather, not to compromise in order to cling to life. "Take up your cross and follow" ... that seems to me a clear reply to Theodicy. Now what we need is some way to instill the same lack of fear into organizations, and the Kingdom will have arrived, we can start making the next kind of progress.

"... that fear of a pink slip, that anxiety, keeps me docile and slavish." The real stinger here is, unless you prove a willingness to be intimidated, they won't let you play at all. Me personally, I'm a dead man already.

Two more books on the pile! Yea!

Thanks Stephen. I have to admit that during the 'protestant' version I found myself wondering if that is really what people believe - it sounds so ridiculous. I liked the way your telling of the 'orthodox' view simply wove together key scripture passages all from the narrative we have of Jesus' life. I wonder if you could use the same technique to tell the 'protestant' view.

I would argue Satan is more an accuser and an unconscious/unintentional agent of evil rather than deliberate. You can't shoot the prosecutor just because you favour the defendant. You have to prove him wrong. It is after you prove him wrong that you accuse him of crimes. Because if you do it at the same time, you'll give him the political victory, and defendant that you want free will burn with him.

This is great. Thank you!