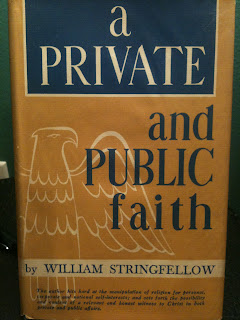

The dust jacket of my first edition of A Private and Public Faith is pictured here. The quote at the bottom reads:

The author hits hard at the manipulation of religion for personal, corporate and national self-interests; and sets forth the possibility and content of a relevant and honest witness to Christ in both private and public affairs.The back cover of the dust jacket has a quote from Karl Barth describing Stringfellow as "the conscientious and thoughtful New York attorney who caught my attention more than any other person." As most fans of Stringfellow know, during Barth's visit to America Stringfellow and he interacted (with others) in a public discussion. Barth was so impressed with Stringfellow's questions and comments he looked at the American audience and said, "Listen to this man!"

In the Preface of A Private and Public Faith Stringfellow describes the goal of the book:

As I find it, religion in America is characteristically atheistic or agnostic. Religion has virtually nothing to do with God and has little to do with the practical lives of men and women in society. Religion seems, mainly, to have to do with religion. The churches--particularly of Protestantism--in the United States are, to a great extent, preoccupied with religion rather than with the gospel.In the first edition the book runs 91 pages (most of Stringfellow's books are short) and is divided into fours chapters: The Folly of Religion, The Specter of Protestantism, The Simplicity of the Christian Life, and The Fear of God. In typical Stringfellow style at the start of each chapter a quote from the bible is given. In A Private and Public Faith Stringfellow works from Colossians, quoting a verse at the start of each chapter. For the four chapters we have Colossians 2.8, 2.20, 3.17, and 1.28.

That, in brief, is the substance of the essays in this tract.

In the next four posts I'll summarize and quote from each of the four chapters in A Private and Public Faith. We start with Chapter 1, The Folly of Religion.

Stringfellow begins the book with a distinction between religion and the gospel. Religion, according to Stringfellow, is mainly preoccupied with itself. But the gospel, by contrast, is preoccupied with life, every facet of life:

Christ bespeaks the care of God for everything to do with actual life, with life as it is lived by anybody and everybody day in and day out. Christ bespeaks my life: in all its detail and mistake and humor and fatigue and surprise and contradiction and freedom and ambiguity and quiet and wonder and sin and peace and vanity and variety and lust and triumph and defeat and rest and love and all the rest it is from time to time; and, cheer up, with your life, just as much, in as full intimacy, touching your whole biography, abiding every secret, with you, whoever, wherever your are, any time, any place.1And if this is so, if Christ is involved in every aspect of life, then the gospel is going to escape the quarantine of the sanctuary and impact how we think about political arrangements and economics. This is controversial because, as Stringfellow notes: "Religion, it is insisted, is for the sanctuary, not the marketplace." But according to Stringfellow, such a belief is atheistic. True Christian belief is very much engaged with marketplaces and, thus, functions as a form of protest inviting antagonism and controversy:

So long as religion is quiet about society it upholds whatever is the prevailing status quo in society. But if one benefits, or is persuaded that he benefits, from the preservation of the status quo, then so long as religion remains aloof from society, it is not controversial. It is only when religion disrupts or threatens one's self-interest that it is condemned as controversial.The problem, according to Stringfellow, is that the Christian church is not committed to this sort of radical protest. Rather, Christian churches are focused on two things: 1) Their own institutional well-being and 2) the moral piety of their members.

...The Christian is committed permanently to radical protest in society. The Christian is always dissatisfied with the existing state of affairs.

Regarding this latter--the focus on individual piety--Stringfellow makes an interesting critique. He argues that you can't be moral all by yourself. An individual is unable to discern, on their own, what is right from wrong. My morality can't be separated from the common lot of humanity:

...[R]eligion, too, grossly oversimplifies the reality of moral conflict in the world, including moral conflict within the private lives of individuals. Religion of this sort fails to apprehend the intense ambiguity of moral decision. This variety of religion contends that it is possible for an individual, in the sphere of his own immediate affairs, to discern what is right and wrong, and to implement a decision so informed with more or less discipline. But the truth is that the extent of any individual's insight into what is good or bad reaches only to that which is advantageous to ourselves. A person may, indeed, be able to figure out what is good, or bad, for him or his family. But that which is good for him, is bad for someone else, and, in principle, for everyone else in the world. The intensity and complexity of the moral conflict is the assertion and pursuit of each individual's own self-interest as over against that of every other person.In short, religion can't be focused on piety as piety is self-interest dressed up in religion garb. Good and evil can only be discerned by looking at the whole of society.

...It is the essence of human sin for us to boast of the power to discern what is good and what is evil, and thus be like God.

Thus, the Christian moral witness is inherently political and economic, rather than pietistic, in nature.

On to Part 2 of 4

...

1A problem with Stringfellow's early writings is his use of masculine pronouns. This can be off-putting. For all the posts in this series I follow the lead of Kellerman in editing Stringfellow's quotes to make them either gender neutral or to use feminine pronouns in a balanced way.

Wow - that's sounds pretty fresh. I was reading yesterday about the sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) who drew a line of descent between the Protestant reformation and certain contemporary expressions of capitalism. Of interest here is his argument that Calvinism's most significant cultural legacy was in generating the psychological impulses underlying modern markets. His thesis leaves me wondering how much chance we have of discerning moral evils as Stringfellow exhorts let alone acting upon them. When Adam Smith wrote of an 'invisible hand' bringing public good from self-interest, he presumably believed himself. God save us from unintended consequences.

"....It is the essence of human sin for us to boast of the power to discern what is good and what is evil, and thus be like God."

"A person may, indeed, be able to figure out what is good, or bad, for

him or his family. But that which is good for him, is bad for someone

else, and, in principle, for everyone else in the world. The

intensity and complexity of the moral conflict is the assertion and

pursuit of each individual's own self-interest as over against that of

every other person."

Including those of William Stringfellow. This is circular logic on a grand scale. He might have been astute in his assessment of an institution, but unless Stringfellow was something other than human, he must be included in that group which would be, by his definition, unable to (correctly) discern that which is good from that which is evil. So why did he bother?

It is possible for Evil to reach down and touch the life of an individual human being while still in the womb. You could not be more isolated at that point from your culture, society, or church. After being born, you must, as an individual, face that evil every day of your life. And while the church as a institution may have no clue or answer to your "problem", neither does any individual. At its very core it is a problem only between you and your maker. And it may require an entire lifetime to even begin to understand it.

"At its very core it is a problem only between you and your maker."

That's a pretty strong claim that many of us would reject as unwarranted. After all, we do see the wide-ranging social effects of sin. Can you talk about this in a different way that brings us other-minded folks into the conversation?

Hi Sam

I agree with your diagnosis, but would perhaps differ with you on treatment. I think it is our duty to continually strive to "do all the good we can in all the places we can for as long as ever we can": I also think we need to strive just as conscientiously to consider that we may be wrong, that we may be part of the problem; to reflect on other possibilities.

For example, in my own work, this tension has led me away from attempts at heroic innovation (a reference to a seminal paper on bringing about organisational change) and towards efforts to create respectful emotional spaces within which change can take place (this isn't as woolly an enterprise as it may sound). Perhaps sometimes all we can do is to ask the right questions.

I'm thinking Stringfellow suggests that we need to discern good and evil in community, casting as wide a net as possible; and that in fact, much of his insight into good and evil were gained in exactly that way. Even then, we discern "in fear and trembling" and with a sense of humility. He seems to argue that the more narrowly one tries to engage in discernment (say at the level of family or individual), the farther from the mark one is likely to get from the truth about good and the more one is likely to play at God. Even at the level of community, we tend to become institutionalized, create "isms" and movements which are themselves fallen. Nevertheless, the Spirit seems to move more through community discernment than through the individual....

I really like your double-edged point (mixed metaphor?) about community, Ronald - post-enlightenment individualism seems to be part of the problem here and unlikely to provide too many solutions.

"A person may, indeed, be able to figure out what is good, or bad, for

him or his family. But that which is good for him, is bad for someone

else, and, in principle, for everyone else in the world. The

intensity and complexity of the moral conflict is the assertion and

pursuit of each individual's own self-interest as over against that of

every other person."

VERSUS.....

"...It is the essence of human sin for us to boast of the power to discern what is good and what is evil, and thus be like God."

I do not believe that Stringfellow can have it both ways. So, which statement is true? If I am, by virtue of my birth, in some way deformed or "damaged", either physically or mentally, how is that a "moral conflict" for anyone other than me? It is not the fault of the state, the church, society, politics, or economics. Indeed, how am I to assess the "morality" of my own life, if I must constantly be in opposition to the status quo, whether religious, political, or economic?

My own particular "problem" has nothing to do with external things or events. I must initially make judgments about what evil is apart from the external world around me. I must confront it at the level of my DNA. Beyond that, if I am unable to "discern what is good and what is evil" because only God can do that, then as an individual I have no more moral authority that does any institution I may wish to confront.

"But the truth is that the extent of any individual's insight into what

is good or bad reaches only to that which is advantageous to ourselves."

What, then, would Stringfellow have us be? Fish? Rocks? Obviously beyond making this assertion, he had to explain exactly that which he claims is the province of the Divine alone.

Stringfellow famously quipped in one of his later books: "Consistency is not a Christian virtue"... : )

Ronald,

Thank you for your thoughts. I do appreciate the insight which you express here. I am just not willing, at this point in my own journey, to voluntarily concede this much power and authority to the community, no matter its composition.

And I do see a glaring inconsistency in Stringfellow's argument which tends to negate it. I prefer Lewis' moral vision of universal innate and inborn conscience. It better explains the world I see around me.

Thanks, Richard, for focusing us on how personal piety or the moral codes of religions can lead us into sinfulness. The problem is that most of the time being "good" means "good like me" and so is by definition casting out others who don't look, sound or think like me. When we are "good like God" we don't make distinctions between good and evil. God created the entire world and called all of it good, not just the parts you or I inhabit. Then he asked us rather politely and by giving us everything else we wanted not to get into the good/ bad business. If we are not to eat of that tree, then what does goodness like like? It looks like being for someone, not against them. It looks like forgiveness not judgment. It looks like love not punishment, even for those who aren't good like me. Being good like God is difficult business and requires us to let go of our need to be good.

http://goo.gl/DqZ08

I liked this cartoon, Sam. Thought you might appreciate it as well.

http://searchingforgrace.com/webcomic/the-worst-sin-according-to-eric-pastor-moses/

Right on. And similarly it brought us the "Protestant Work Ethic". I mean if you're one of the elect that could really only be known by the evidences, right? Being industrious and successful seemed, and presumably still seems, to be high on the list of evidences. Ugh.

Wow. I love this post, Suzanne. I've never heard it put quite like that. But you're right. Being good like God is quite different from being "good like me." Acceptance, unconditional love, being for someone and not against them--making your sun to shine on the just and unjust alike...that's the God kind of good...at least according to Jesus it is. And that, as you say, is difficult business.

Thanks, Patricia. I do appreciate that.

Sam,

I think your objections are much too binary.

Stringfellow's main point in the sections you cite is that moral conflict is intensly complex and often ambiguous. Striving to "know right from wrong" really boils down to a method of resolving personal moral conflictedness in that we want what we want and then seek justification for our wants.

Perhaps if we level with ourselves and just pitch out moral justification based on "ethical behavior" and fess up to our inherent self-centeredness then maybe we can realize the power of love lived out in an atmosphere of accepted responsibility for both ourselves and others.

T

It rocked my world when I first heard -- it's pure James Alison. If you haven't read anything by him you might try "The Joy of Being Wrong" or "Undergoing God".