i.

He was despised and rejected by men,

a man of sorrows, and familiar with suffering.

Like one from whom men hide their faces

he was despised, and we esteemed him not.

Surely he took up our infirmities

and carried our sorrows,

yet we considered him stricken by God,

smitten by him, and afflicted.

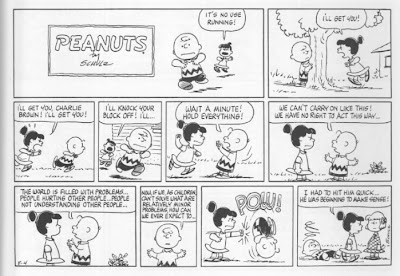

Charlie Brown is a weird kid. He's odd. He's unpopular. He's insignificant. Consequently, when we see Charlie Brown suffer abuse or indignities we are amused. Even entertained. But over the course of the strip our feelings about Charlie Brown begin to change. This weird kid begins to appear heroic in the face of all he suffers. As David Michaelis writes, "Charlie Brown handles without self-pity insults that would push real children to the breaking point...Schulz's characters remind people of the never-ceasing struggle to confront one's vulnerabilities with dignity." (1)

Eventually, we begin to identify with this weird kid, to see ourselves in his sufferings: "Readers recognized themselves in 'poor, moon-faced, unloved, misunderstood' Charlie Brown--in his dignity in the face of whole seasons of doomed ball games, his endurance and stoicism in the face of insults--because he is willing to admit that just to keep on being Charlie Brown is an exhausting and painful process. Charlie Brown reminded people, as no other cartoon character had, of what it was to be vulnerable, to be small and alone in the universe, to be human--both little and big at the same time." (2)

We see ourselves in Charlie Brown. And by seeing ourselves in this weird kid we begin to stand with all the weird kids. In standing with Charlie Brown we stand with all those who suffer abuse, disappointment, and failure. We stand in solidarity with all those kids not picked for the playground kickball game.

One of the deepest theological themes of Peanuts is how it makes this weird kid, Charlie Brown, the hero. More precisely, Charlie Brown is an anti-hero. A victim is the protagonist of Peanuts. And in this odd move Peanuts draws us into solidarity with victims.

Obviously, this hero-victim-solidarity motif sits at the core of the Christian faith. In Christianity the victim is deified. God stands in solidarity with those who suffer. Jesus stands in the place of the weird, odd, and marginalized.

These themes are given voice by Jurgen Moltmann in his book The Crucified God:

"In Christ, God and our neighbor are a unity...The crucified Christ became the brother of the despised, abandoned and oppressed. And this is why brotherhood with the 'least of his brethren' is a necessary part of brotherhood with Christ and identification with him...Christian identification with the crucified necessarily brings them into solidarity with the alienated of this world, with the dehumanized and the inhuman." (3)

In sum, Moltmann argues that Christian love is, at root, love for the Charlie Brown's of the world:

"...the church of the crucified Christ cannot consist of an assembly of like persons who mutually affirm each other, but must be constituted of unlike persons...[F]or the crucified Christ, the principle of fellowship is fellowship with those who are different, and solidarity with those who have become alien and have been made different. Its power is not friendship, the love for what is similar and beautiful, but creative love for what is different, alien and ugly." (4)

ii.

But he was pierced for our transgressions,

he was crushed for our iniquities;

the punishment that brought us peace was upon him,

and by his wounds we are healed.

He was oppressed and afflicted,

yet he did not open his mouth;

he was led like a lamb to the slaughter,

and as a sheep before her shearers is silent,

so he did not open his mouth.

But there is more than solidarity with the victim in Peanuts. As we watch Charlie Brown suffer, his innocent non-retalitory response begins to unmask the violence around him. The violence seems so much more violent when directed at Charlie Brown. As Michaelis notes, when Charlie Brown absorbs violence "no rage boils up, no self-pity spills over, no tears are shed, no punch line squeezed out--just silent endurance." (5)

This "silent endurance" begins to unmask, highlight, and indict the violence. As Umberto Eco noted, Charlie Brown "acts in all purity and without any guile", and, as a result, "society is prompt to reject him..."

In the Christian story, the innocence of the Lamb of God is critical to the unmasking of human violence. Because Jesus is innocent, as is Charlie Brown, the insanity of violence is made salient. The innocence of the Lamb makes it painfully obvious that the violence is unjustified. And this calls into question all forms of justification for violence. The Christian story asks: How do you know it isn't God you are killing? The cross of Jesus is always sitting there, a constant indictment of human violence. It speaks across the centuries: Look at what you did. How can humans be trusted to kill if this is what you did to innocence and goodness? As Mark Heim has written in his book Saved from Sacrifice: "In the Gospel of Luke, at the moment of Jesus' death the centurion at the cross exclaims, 'Surely this man was innocent.' This is not the voice of [voilence-justifying religious] myth. It is a profound counterconfession, a voice of dissent..." (6)

This "voice of dissent" indicts the self-interested rationalizations that humans use to justify their scapegoating violence. When the victim is clearly proclaimed to be innocent violence stands unmasked and a route to salvation is opened. As Heim continues:

A Golgotha the "scapegoating process is stripped of its sacred mystery, and the collective persecution and abandonment are painfully illustrated for what they are, so that no one, including the disciples, the proto-Christians, can honestly say afterward that they resisted the sacrificial tide. In myth no victims are visible as victims, and therefore neither are any persecutors. But in the New Testament the victim is unmistakably visible and the collective persecutors (including in the end virtually everyone) and their procedures are illustrated in sharp clarity.

...The free, loving 'necessity' that lead God to be willing to stand in the place of the scapegoat is that this is the way to unmask the sacrificial mechanism, to break its cycles of mythic reproduction, and to found human community on a nonsacrificial principle: solidarity with the victim, not unanimity against the victim." (7)

In short, I read Peanuts as a Christian text. I see the victim as the hero. I'm drawn into solidarity with the odd, weird, weak, and ugly. And I see in the quiet dignity of Charlie Brown a shadow the cross, a place where human violence is unmasked for the cruelty that it is. Images from The Complete Peanuts by Fantagraphics Books

Images from The Complete Peanuts by Fantagraphics Books

--End Chapter 7--

Notes:

(1) p. 189 Schulz and Peanuts

(2) p. 247 Ibid

(3) p. 24, 25 The Crucified God

(4) p. 28 Ibid

(5) p. 269 Schulz and Peanuts

(6) p. 116 Saved from Sacrifice

(7) p. 114 Ibid

Email Subscription on Substack

Richard Beck

Welcome to the blog of Richard Beck, author and professor of psychology at Abilene Christian University (beckr@acu.edu).

Welcome to the blog of Richard Beck, author and professor of psychology at Abilene Christian University (beckr@acu.edu).

The Theology of Faërie

The Little Way of St. Thérèse of Lisieux

The William Stringfellow Project (Ongoing)

Autobiographical Posts

- On Discoveries in Used Bookstores

- Two Brothers and Texas Rangers

- Visiting and Evolving in Monkey Town

- Roller Derby Girls

- A Life With Bibles

- Wearing a Crucifix

- Morning Prayer at San Buenaventura Mission

- The Halo of Overalls

- Less

- The Farmer's Market

- Subversion and Shame: I Like the Color Pink

- The Bureaucrat

- Uncle Richard, Vampire Hunter

- Palm Sunday with the Orthodox

- On Maps and Marital Spats

- Get on a Bike...and Go Slow

- Buying a Bible

- Memento Mori

- We Weren't as Good as the Muppets

- Uncle Richard and the Shark

- Growing Up Catholic

- Ghostbusting (Part 1)

- Ghostbusting (Part 2)

- My Eschatological Dog

- Tex Mex and Depression Era Cuisine

- Aliens at Roswell

On the Principalities and Powers

- Christ and the Powers

- Why I Talk about the Devil So Much

- The Preferential Option for the Poor

- The Political Theology of Les Misérables

- Good Enough

- On Anarchism and A**holes

- Christian Anarchism

- A Restless Patriotism

- Wink on Exorcism

- Images of God Against Empire

- A Boredom Revolution

- The Medal of St. Benedict

- Exorcisms are about Economics

- "Scooby-Doo, Where Are You?"

- "A Home for Demons...and the Merchants Weep"

- Tales of the Demonic

- The Ethic of Death: The Policies and Procedures Manual

- "All That Are Here Are Humans"

- Ears of Stone

- The War Prayer

- Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Experimental Theology

- Eucharistic Identity

- Tzimtzum, Cruciformity and Theodicy

- Holiness Among Depraved Christians: Paul's New Form of Moral Flourishing

- Empathic Open Theism

- The Victim Needs No Conversion

- The Hormonal God

- Covenantal Substitutionary Atonement

- The Satanic Church

- Mousetrap

- Easter Shouldn't Be Good News

- The Gospel According to Lady Gaga

- Your God is Too Big

From the Prison Bible Study

- The Philosopher

- God's Unconditional Love

- There is a Balm in Gilead

- In Prison With Ann Voskamp

- To Make the Love of God Credible

- Piss Christ in Prison

- Advent: A Prison Story

- Faithful in Little Things

- The Prayer of Jabez

- The Prayer of Willy Brown

- Those Old Time Gospel Songs

- I'll Fly Away

- Singing and Resistence

- Where the Gospel Matters

- Monday Night Bible Study (A Poem)

- Living in Babylon: Reading Revelation in Prison

- Reading the Beatitudes in Prision

- John 13: A Story from the Prision Study

- The Word

Series/Essays Based on my Research

The Theology of Calvin and Hobbes

The Theology of Peanuts

The Snake Handling Churches of Appalachia

Eccentric Christianity

- Part 1: A Peculiar People

- Part 2: The Eccentric God, Transcendence and the Prophetic Imagination

- Part 3: Welcoming God in the Stranger

- Part 4: Enchantment, the Porous Self and the Spirit

- Part 5: Doubt, Gratitude and an Eccentric Faith

- Part 6: The Eccentric Economy of Love

- Part 7: The Eccentric Kingdom

The Fuller Integration Lectures

Blogging about the Bible

- Unicorns in the Bible

- "Let My People Go!": On Worship, Work and Laziness

- The True Troubler

- Stumbling At Just One Point

- The Faith of Demons

- The Lord Saw That She Was Not Loved

- The Subversion of the Creator God

- Hell On Earth: The Church as the Baptism of Fire and the Holy Spirit

- The Things That Make for Peace

- The Lord of the Flies

- On Preterism, the Second Coming and Hell

- Commitment and Violence: A Reading of the Akedah

- Gain Versus Gift in Ecclesiastes

- Redemption and the Goel

- The Psalms as Liberation Theology

- Control Your Vessel

- Circumcised Ears

- Forgive Us Our Trespasses

- Doing Beautiful Things

- The Most Remarkable Sequence in the Bible

- Targeting the Dove Sellers

- Christus Victor in Galatians

- Devoted to Destruction: Reading Cherem Non-Violently

- The Triumph of the Cross

- The Threshing Floor of Araunah

- Hold Others Above Yourself

- Blessed are the Tricksters

- Adam's First Wife

- I Am a Worm

- Christus Victor in the Lord's Prayer

- Let Them Both Grow Together

- Repent

- Here I Am

- Becoming the Jubilee

- Sermon on the Mount: Study Guide

- Treat Them as a Pagan or Tax Collector

- Going Outside the Camp

- Welcoming Children

- The Song of Lamech and the Song of the Lamb

- The Nephilim

- Shaming Jesus

- Pseudepigrapha and the Christian Witness

- The Exclusion and Inclusion of Eunuchs

- The Second Moses

- The New Manna

- Salvation in the First Sermons of the Church

- "A Bloody Husband"

- Song of the Vineyard

Bonhoeffer's Letters from Prision

Civil Rights History and Race Relations

- The Gospel According to Ta-Nehisi Coates (Six Part Series)

- Bus Ride to Justice: Toward Racial Reconciliation in the Churches of Christ

- Black Heroism and White Sympathy: A Reflection on the Charleston Shooting

- Selma 50th Anniversary

- More Than Three Minutes

- The Passion of White America

- Remembering James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman

- Will Campbell

- Sitting in the Pews of Ebeneser Baptist Church

- MLK Bedtime Prayer

- Freedom Rider

- Mountiantop

- Freedom Summer

- Civil Rights Family Trip 1: Memphis

- Civil Rights Family Trip 2: Atlanta

- Civil Rights Family Trip 3: Birmingham

- Civil Rights Family Trip 4: Selma

- Civil Rights Family Trip 5: Montgomery

Hip Christianity

The Charism of the Charismatics

Would Jesus Break a Window?: The Hermeneutics of the Temple Action

Being Church

- Instead of a Coffee Shop How About a Laundromat?

- A Million Boring Little Things

- A Prayer for ISIS

- "The People At Our Church Die A Lot"

- The Angel of Freedom

- Washing Dishes at Freedom Fellowship

- Where David Plays the Tambourine

- On Interruptibility

- Mattering

- This Ritual of Hallowing

- Faith as Honoring

- The Beautiful

- The Sensory Boundary

- The Missional and Apostolic Nature of Holiness

- Open Commuion: Warning!

- The Impurity of Love

- A Community Called Forgiveness

- Love is the Allocation of Our Dying

- Freedom Fellowship

- Wednesday Night Church

- The Hands of Christ

- Barbara, Stanley and Andrea: Thoughts on Love, Training and Social Psychology

- Gerald's Gift

- Wiping the Blood Away

- This Morning Jesus Put On Dark Sunglasses

- The Only Way I Know How to Save the World

- Renunciation

- The Reason We Gather

- Anointing With Oil

- Incarnations of God's Mercy

Exploring Preterism

Scripture and Discernment

- Owning Your Protestantism: We Follow Our Conscience, Not the Bible

- Emotional Intelligence and Sola Scriptura

- Songbooks vs. the Psalms

- Biblical as Sociological Stress Test

- Cookie Cutting the Bible: A Case Study

- Pawn to King 4

- Allowing God to Rage

- Poetry of a Murderer

- On Christian Communion: Killing vs. Sexuality

- Heretics and Disagreement

- Atonement: A Primer

- "The Bible says..."

- The "Yes, but..." Church

- Human Experience and the Bible

- Discernment, Part 1

- Discernment, Part 2

- Rabbinic Hedges

- Fuzzy Logic

Interacting with Good Books

- Christian Political Witness

- The Road

- Powers and Submissions

- City of God

- Playing God

- Torture and Eucharist

- How Much is Enough?

- From Willow Creek to Sacred Heart

- The Catonsville Nine

- Daring Greatly

- On Job (Gutiérrez)

- The Selfless Way of Christ

- World Upside Down

- Are Christians Hate-Filled Hypocrites?

- Christ and Horrors

- The King Jesus Gospel

- Insurrection

- The Bible Made Impossible

- The Deliverance of God

- To Change the World

- Sexuality and the Christian Body

- I Told Me So

- The Teaching of the Twelve

- Evolving in Monkey Town

- Saved from Sacrifice: A Series

- Darwin's Sacred Cause

- Outliers

- A Secular Age

- The God Who Risks

Moral Psychology

- The Dark Spell the Devil Casts: Refugees and Our Slavery to the Fear of Death

- Philia Over Phobia

- Elizabeth Smart and the Psychology of the Christian Purity Culture

- On Love and the Yuck Factor

- Ethnocentrism and Politics

- Flies, Attention and Morality

- The Banality of Evil

- The Ovens at Buchenwald

- Violence and Traffic Lights

- Defending Individualism

- Guilt and Atonement

- The Varieties of Love and Hate

- The Wicked

- Moral Foundations

- Primum non nocere

- The Moral Emotions

- The Moral Circle, Part 1

- The Moral Circle, Part 2

- Taboo Psychology

- The Morality of Mentality

- Moral Conviction

- Infrahumanization

- Holiness and Moral Grammars

The Purity Psychology of Progressive Christianity

The Theology of Everyday Life

- Self-Esteem Through Shaming

- Let Us Be the Heart Of the Church Rather Than the Amygdala

- Online Debates and Stages of Change

- The Devil on a Wiffle Ball Field

- Incarnational Theology and Mental Illness

- Social Media as Sacrament

- The Impossibility of Calvinistic Psychotherapy

- Hating Pixels

- Dress, Divinity and Dumbfounding

- The Kingdom of God Will Not Be Tweeted

- Tattoos

- The Ethics of :-)

- On Snobbery

- Jokes

- Hypocrisy

- Everything I learned about life I learned coaching tee-ball

- Gossip, Part 1: The Food of the Brain

- Gossip, Part 2: Evolutionary Stable Strategies

- Gossip, Part 3: The Pay it Forward World

- Human Nature

- Welcome

- On Humility

Jesus, You're Making Me Tired: Scarcity and Spiritual Formation

A Progressive Vision of the Benedict Option

George MacDonald

Jesus & the Jolly Roger: The Kingdom of God is Like a Pirate

Alone, Suburban & Sorted

The Theology of Monsters

The Theology of Ugly

Orthodox Iconography

Musings On Faith, Belief, and Doubt

- The Meanings Only Faith Can Reveal

- Pragmatism and Progressive Christianity

- Doubt and Cognitive Rumination

- A/theism and the Transcendent

- Kingdom A/theism

- The Ontological Argument

- Cheap Praise and Costly Praise

- god

- Wired to Suffer

- A New Apologetics

- Orthodox Alexithymia

- High and Low: The Psalms and Suffering

- The Buddhist Phase

- Skilled Christianity

- The Two Families of God

- The Bait and Switch of Contemporary Christianity

- Theodicy and No Country for Old Men

- Doubt: A Diagnosis

- Faith and Modernity

- Faith after "The Cognitive Turn"

- Salvation

- The Gifts of Doubt

- A Beautiful Life

- Is Santa Claus Real?

- The Feeling of Knowing

- Practicing Christianity

- In Praise of Doubt

- Skepticism and Conviction

- Pragmatic Belief

- N-Order Complaint and Need for Cognition

Holiday Musings

- Everything I Learned about Christmas I Learned from TV

- Advent: Learning to Wait

- A Christmas Carol as Resistance Literature: Part 1

- A Christmas Carol as Resistance Literature: Part 2

- It's Still Christmas

- Easter Shouldn't Be Good News

- The Deeper Magic: A Good Friday Meditation

- Palm Sunday with the Orthodox

- Growing Up Catholic: A Lenten Meditation

- The Liturgical Year for Dummies

- "Watching Their Flocks at Night": An Advent Meditation

- Pentecost and Babel

- Epiphany

- Ambivalence about Lent

- On Easter and Astronomy

- Sex Sandals and Advent

- Freud and Valentine's Day

- Existentialism and Halloween

- Halloween Redux: Talking with the Dead

The Offbeat

- Batman and the Joker

- The Theology of Ugly Dolls

- Jesus Would Be a Hufflepuff

- The Moral Example of Captain Jack Sparrow

- Weddings Real, Imagined and Yet to Come

- Michelangelo and Neuroanatomy

- Believing in Bigfoot

- The Kingdom of God as Improv and Flash Mob

- 2012 and the End of the World

- The Polar Express and the Uncanny Valley

- Why the Anti-Christ Is an Idiot

- On Harry Potter and Vampire Movies

Charlie Brown as unmasking cruelty in the comics and like Christ in that respect - I can see that.

Have not totally thought it through, but your post brings to mind an incident from grade school I never forgot.

Steve was an overweight kid and also below average academically - one of those kids who was generally and regularly ridiculed.

One morning in fifth or sixth grade, we had a substitute teacher who wasn't well liked - controlled the class through intimidation. That morning somebody had let out a whistle shortly before recess. She asked who did it. Nobody said a word. She said we were all going to stay in and miss the entire recess if necessary until the person who whistled confessed.

Suddenly from a far corner of the room, Steve, in tears, blurted out that he had done it. But I had clearly heard, and so had everybody else, that the sound had definitely come from the opposite side of the room.

There was this mass, spontaneous vocalization that no, it wasn't Steve - the whole class rose to his defense. It was amazing.

So even real life Charlie Browns can be somewhat transformative.

Paul,

What a great story. I'm glad I did this series if just to hear that story. Thank for sharing it.

I am enjoying each chapter with renewed appreciation for Schutlz and for your writing gifts. This deserves to be published.

Don in AZ

"Saved from Sacrifice" sounds like an incredible book.

Good series, Richard. I look forward to the next one.