Over the last year some students and I have been involved in some research into the PostSecret phenomenon. Earlier this month we presented five papers in a symposium entitled The PostSecret Phenomenon: The Psychology of Anonymous Confession at the annual Southwestern Psychological Association conference held, this year, in Kansas City, MO.

Over the last year some students and I have been involved in some research into the PostSecret phenomenon. Earlier this month we presented five papers in a symposium entitled The PostSecret Phenomenon: The Psychology of Anonymous Confession at the annual Southwestern Psychological Association conference held, this year, in Kansas City, MO.

Two of the first questions we had about PostSecret were these:

#1. Are the secrets we find in PostSecret (at the PostSecret Sundays website and in the publications) typical of the secrets you and I might have? That is, is PostSecret representative of the normal population?

#2. Along these lines, is PostSecret sensationalized? That is, as a website and as a publication series PostSecret may be selectively choosing secrets that grab our attention to create more web hits or book sales.

But to answer these questions we faced a challenge. We couldn't do preliminary tests of these questions until we got a handle on the PostSecret "content" (i.e., what the secrets were about). Until the content was ballparked we couldn't move on to how the content of the PostSecret secrets might or might not be representative of the content of "real world" secrets (i.e., the secrets you or I have).

To start this process we examined the content of the three PostSecret publications that were available to us at the start of the project in June 2007: PostSecret, My Secret, and The Secret Lives of Men and Women.

We read through all these secrets and noted that, in our estimation, the secrets could be grouped into three broad areas:

Existential: Secrets related to existential themes such as life meaning/purpose, choice, regret, religious faith, and death.

Relational: Secrets involving relational issues such as fracture, unrequited love, sexuality, isolation, harmony, and romantic anxiety.

Declarative: Descriptive statements about aspects of the the self that are often considered shameful or deviant.

As you can see, after this initial sorting we had sub-codes within each category. Examples and descriptions of these sub-codes follow (click on each for a closer look):

I. Existential sub-codes:

i. Life meaning and purpose: Concerns or hopes about one's overall life purpose or the meaning or value of one's life:

ii. Choice and regret: Negative emotions related to making choices or regret over choices already made:

iii. Religious faith: Secrets related to religious faith, doubts, or loss of faith:

iv. Death: Secrets related to death anxiety or death-related concerns:

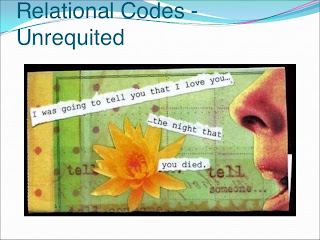

II. Relational sub-codes:

i. Fracture: Relational conflict, failure or brokenness:

ii. Unrequited Love: Expressions of love that are unfulfilled:

iii. Sexual: A secret about the sexual aspect of a relationship:

iv. Isolation: Secrets about a lack of relationality such as loneliness or alienation:

v. Romantic Anxiety: Secrets about romantic worries or preoccupations:

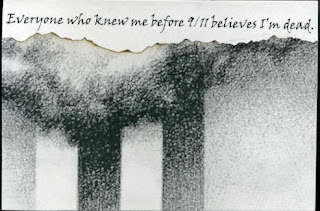

III. Declarative sub-codes:

The Declarative secrets are all self-descriptive statements, but these tended to fall into one of three areas:

i. Mental Health: Secrets about psychological strain (e.g., abuse) or psychological dysfunction (e.g., drug use, suicide):

ii. Sexual: Secrets about one's sexual interests or behaviors:

iii. Self-Trivia: Undisclosed facts (generally odd, bizarre, shameful or deviant in nature) about one's interests or behaviors:

With this coding complete we could examine the relative proportions of secret content found in PostSecret. This analysis revealed that the most common secrets--what we called The Big Three--were the following:

Existential : Meaning

Relational : Fracture

Declarative : Self-Trivia

That is, the most common secrets in PostSecret are secrets about:

Concerns, fears, or sadness over the meaning, purpose, direction or value of your life.

Worries, anger, or sadness over some fractured or failed relationship with a friend, parent, family member, spouse or child.

Some facet of yourself (some interest, trait, or behavior) that you've never disclosed to anyone because you fear that people will find it odd, sick, bizarre, shameful, or deviant.

In short, if PostSecret is an accurate guide (a question I'll hold over for the next post) we can expect that The Big Three would capture the majority of secrets we all keep.

Does it capture yours?

Further, what can The Big Three tell us about the human experience? That is, if our secrets do cluster in these three areas what can we learn about ourselves? And, does this have any spiritual or theological implications?

Into the World--Chapter Three: Today's Warring Intellectual Context

Contents

Contents

Prologue and Abstract

Chapter One: Introduction

Chapter Two: The Layered Gospel Context

Chapter Three: Today’s Warring Intellectual Context

Chapter Four: A Perpetual Warring Intellectual Context

Chapter Five: A Primer—The Bible’s Broadest Theme

Chapter Six: The Voice of Conscience

Chapter Seven: The Voice of God

Chapter Eight: The Message of the Cross as Supreme Answer

Chapter Nine: The View from Enlightened Self-Interest

Chapter Ten: The Challenge from Kantian Autonomy

Chapter Eleven: The View from James’ Radical Question

Chapter Twelve: The View from Sartre’s Bad Faith

Chapter Thirteen: Kierkegaard’s Challenge to Intelligibility—First Part

Chapter Thirteen: Kierkegaard’s Challenge to Intelligibility—Second Part

Epilogue

[Note to readers: Since I grant the challenge to the meaningfulness of religious language contained in reductionistic views such as Dawkins', Hitchens', and Asimov's below, perhaps I should expect to be critiqued by Christians who have taken "the Wittgensteinian turn" in which the subtle contexts and uses of language are given ample consideration. I acknowledge that reductionistic critiques of religion are often simplistic. Nevertheless, it is my sense that the Wittgensteinian turn is a form of the God of the gaps defense of religion and theology: For just because reductionism at present is too crude to account for the sublties of language, it does not follow that, when better developed, the human sciences will not do so. Let me also say that if it turns out that my fear concerning the Wittgensteinian turn is false, that that has no bearing on what follows. I have simply taken a different turn, and one that hope will be judged on its own merits.]

Jesus’ claim that he came into the world to testify to the truth implies a domain of truth beyond the world. The Prologue of The Gospel According to John says that the Godhead itself is that “realm” and that Jesus is to be identified with the Godhead. Now that is a large claim. We can get a better view of the present intellectual climate toward such claims by considering the following exchanges about the possibility of a transcendent realm.

The British magazine Prospect bestowed the title of England’s leading public intellectual on Richard Dawkins in 2004, and Dawkins may be the most famous atheist in the world today. He is also famously vehement in his unbelief. According to an article in Discover magazine, verbal jousting broke out between Dawkins and Brown University professor Ken Miller during a symposium at the New York Institute for the Humanities. Dawkins prompted the jousting when he challenged the legitimacy of Miller’s traditional Christian beliefs.1

One might well be surprised that two eminent scientists who both believe that evolution provides the sole scientific basis for teaching natural history would come to loggerheads over religious belief. Haven’t many scientists and religious authorities been telling us for years that science and religion answer different questions and so do not conflict? In fact, Ken Miller, author of Finding Darwin’s God, is one of the scientists who have been telling us that: “I will persist in saying that religion for me, and for many other people, answers questions that are beyond the realm of science,” he told Dawkins.2 And he added, “I regard Genesis as a spiritual truth. And I also think that Genesis was written in a language that would explain God that was relevant to the people living at the time. I cannot imagine…Moses coming down from the Mount and talking about DNA, RNA, and punctuated equilibrium. …”3

According to the Discovery article, “Dawkins, at the far end of the table, almost levitated out of his seat with indignation. ‘But what does that mean?’ he demanded, voice rising. The audience rewarded his indignation with combustive applause.”4

It seems that “positivism,” the notion that there is nothing cognitively meaningful to be said beyond the realm of science, resonated with the audience—despite the fact that the notion fails by its own criterion (positivism is a philosophical view, not a scientific one). Nevertheless, Dawkins did pose a worthy challenge, best stated in question form: If religion does not supply meanings that can be understood within a scientific framework, within what meaningful framework are we to judge its statements for veracity? Bluntly, how can Jesus meaningfully be “the truth” for a Christian like Miller?

So we are back to the big question. And it poses the critical challenge to a religious person who wants to affirm a truth outside of science’s purview. Thus—without endorsing the “combustive” applause Dawkins’ query received, which suggested a prejudiced crowd—a fair-minded critique of the exchange will acknowledge that Dawkins’ challenge requires a good answer.

We can deepen the question by looking to another forum comprised of intellectuals who were considering—among other topics—the roles of religion and science in the public square. The forum, sponsored by the on-line magazine The Nation to discuss “The Future of the Public Intellectual,” included comments similar in substance and tone to those exchanged between Dawkins and Miller. According to Yale University professor Stephen Carter, “There’s a tendency sometimes to have an uneasy equation that there is serious intellectual activity over here, and religion over there, and these are, in some sense, at war. That people of deep faith are plainly anti-intellectual and serious intellectuals are plainly antireligious bigots—they’re two very serious stereotypes held by very large numbers of people. I’m quite unembarrassed and enthusiastic about identifying myself as a Christian and also as an intellectual… …[though] there are certain prejudices on campus suggesting that is not a possible thing to be or, at least, not a particularly useful combination of labels. … And yet, I think that the tradition of the contribution to a public-intellectual life by those making explicitly religious arguments has been important…”5

As if to confirm the sense of war between science and religion that Stephen Carter noted, columnist for The Nation and forum participant Christopher Hitchens proposed, “The first [task for the public intellectual], I think, in direct opposition to Professor Carter, …[is] to replace the rubbishy and discredited notions of faith with scrutiny…”6 Hitchens went on to say that “This is a time when one page, one paragraph, of Hawking is more awe-inspiring, to say nothing of being more instructive, than the whole of Genesis… Yet we’re still used to [religious] babble.”7 Then, quite interestingly in this context, Hitchens said, “…I think the onus is on us [as public intellectuals] to find a language that moves us beyond faith, because faith is the negation of the intellect…”8

Note the clashing claims about religion made by Hitchens in this forum and Miller in the previous one. Here Hitchens claims that the role of the intellectual—as epitomized by the scientist Stephen Hawking in his estimation—is to take us beyond the anti-intellectualism of religious “babble.” Miller, by contrast, believes that religion answers questions that take us beyond the realm of science.

Yet another exchange will help us focus on the kind of answer needed to make a responsible choice between these conflicting views. Celebrated British television personality, David Frost, used to host a show on which he interviewed famous intellectuals. During the interviews he would sound those who were atheists on the reasons for their unbelief. In an address to The National Press Club in the United States he told the following story as his “most embarrassing moment.”9

Famed atheist and science fiction writer, Isaac Asimov, had rebutted all of Frost’s attempts to gain a concession for theism out of him. In a last ditch attempt to get one Frost implored, “But isn’t it possible that there is something out there that we just don’t know about?”10

Asimov replied, “Yes, but then we just don’t know about it.”11

The moral of the story is that it’s a bad idea to stake one’s belief in God on an empty claim. To the point at hand, if Miller’s contention that religion answers questions beyond the realm of science cannot be given some substantive grounding, his view is no better than Frost’s—and Jesus’ claim to have come into the world to testify to the truth is empty. We would be forced to agree with Nietzsche that Pilate’s famous question is the only saying that has value in the New Testament.

CHAPTER THREE NOTES

1. Stephen S. Hall, “Darwin’s Rottweiler,” Discover, Vol. 26 No. 9, September 2005, p. 55(www.discover.com/issues/sep-05/features/darwins-rottweiler).

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid, p. 56.

4. Ibid.

5. Quoted in “The Future of the Public Intellectual: A Forum” in The Nation, February 12, 2001 (www.thenation.com/doc/20010212/forum).

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. David Frost in a National Press Club address from March, 1990 (as recalled by the author, who heard the address over National Public Radio: no recording of the address is available).

10. Ibid. Asimov was quoted by Frost.

11. Ibid.

PostSecret: Part 1, PostSecret and Church

PostSecret was started by Frank Warren in 2004 when he sent off 3,000 self-addressed stamped postcards asking people to reveal a secret, anonymously, and mail it back to him. The postcard was to be decorated in a self-expressive or thematic manner. Warren received hundreds of responses which formed the basis of a community art project.

PostSecret was started by Frank Warren in 2004 when he sent off 3,000 self-addressed stamped postcards asking people to reveal a secret, anonymously, and mail it back to him. The postcard was to be decorated in a self-expressive or thematic manner. Warren received hundreds of responses which formed the basis of a community art project.

And the secrets kept coming. Eventually, Warren started the PostSecret Sundays blog where, every Sunday, Warren uploads a selection of the secrets he has received that week.

Further, PostSecret has become a publishing phenomenon with four best-selling books now out: PostSecret, My Secret, The Secret Lives of Men and Women, and A Lifetime of Secrets.

To participate in PostSecret you must do the following (from the PostSecret website):

You are invited to anonymously contribute your secrets to PostSecret. Each secret can be a regret, hope, funny experience, unseen kindness, fantasy, belief, fear, betrayal, erotic desire, feeling, confession, or childhood humiliation. Reveal anything - as long as it is true and you have never shared it with anyone before.

Create your 4-by-6-inch postcards out of any mailable material. If you want to share two or more secrets, use multiple postcards. Put your complete secret and image on one side of the postcard.

Tips:

Be brief - the fewer words used the better.

Be legible - use big, clear and bold lettering.

Be creative - let the postcard be your canvas.

Mail your secrets, or other correspondence, to:

PostSecret

13345 Copper Ridge Road

Germantown, Maryland

USA 20874-3454

Please consider sharing a follow-up story about how mailing in a secret, or reading someone else's, made a difference in your life.

Since its inception PostSecret has acquired a wide following. Many think PostSecret reached its cultural tipping point when the rock band All American Rejects used PostSecret and PostSecret participants as the motif for their music video Dirty Little Secret:

As a Christian and psychologist I’m fascinated by the PostSecret phenomenon. I'm particularly struck my the many reports of psychological and emotional healing that PostSecret participants--those sending in secrets and those who regularly read them--consistently report. This healing aspect of PostSecret is dramatically captured by this video produced by Frank Warren:

Beyond psychological healing, PostSecret has also caused me to think deeply about the failures of the church and modern Christianity. Specifically, the church claims to be a place, a community, that values confession, honesty, transparency, and authenticity. And yet, few experience churches in this way. Rather, churches tend to be places filled with hypocrisy, shallowness, pretend, and pretense. The younger generation increasingly sees the church as "fake."

These same young people are flocking to PostSecret, a place and community they find to be more authentic, real, gritty and accepting.

No doubt, many with find PostSecret odd, exhibitionistic, ill, and voyeuristic. I think these adjectives do apply. But at its core I think PostSecret has touched a nerve and is meeting a need. A need for authenticity and acceptance that the church has failed to address.

Ugly: Part 7, Christina's World

Dan, my friend and colleague, returned to our class on Ugly this week to speak about how art offers us a metaphor regarding the redemption of the "ugly."

Dan, my friend and colleague, returned to our class on Ugly this week to speak about how art offers us a metaphor regarding the redemption of the "ugly."

In his book Status Anxiety, Alain de Botton observes how in art's portrayal of the mundane, everyday, and lower class an artist can subvert our cultural expectations about what is worthy of honor and esteem. de Botton's concerns are about status while mine are about the beautiful and the ugly, but the projects are similar in many ways: An artist can take something that is lower status (e.g., the ugly) and transform it, via her moral and aesthetic vision, into something honorable and beautiful. As de Botton writes (p. 143), "[The works of some artists] appear to suggest that if such commonplaces as the sky on a summer's evening, a pitted wall heated by the sun and the face of an unknown woman as she peels an egg for sick person are truly among the loveliest sights we may hope ever to lay our eyes on, then perhaps we are honour-bound to question the value of much that we have been taught to respect and aspire to. It may seem far-fetched to hang a quasipolitical programme on a jug placed on a sideboard, or on a cow grazing in a pasture, but the moral of [this] work...may help us to correct many of our snobbish preconceptions regarding what there is to esteem and honor in the world."

In short, the eye of an artist is a metaphor for the eye of God and, thus, the eye of the Christian. That is, we find, because of the unique way we see the world, beauty in the ugly and honor in what the world discards.

Dan walked us through many examples of this metaphor, but the one that struck me most was the painting Christina's World.

Many consider Christina's World to be Andrew Wyeth's most famous painting. As most know, Wyeth is an American painter of the realist school. Wyeth's favorite subjects are the landscapes and his neighbors from his hometown of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania and his summer home in Cushing, Maine. As we noted with de Botton, Wyeth picks landscapes and people that are not generally considered to be "beautiful." But through his paintings Wyeth redeems, honors, and elevates his subject matter. Christina's World is a wonderful example of this (please click on the picture below for a closer view):

First, consider the way Wyeth renders the landscape. Living in West Texas I often drive through flat, brown, and treeless landscapes. Thus. many people find West Texas "ugly." I grew up in Pennsylvania so I understand where this comes from. But I've come to disagree with the majority view. I now find these West Texas landscapes to be beautiful. I like to think I see the landscape the way Wyeth sees his landscapes. What appears monochromatic at first glance, if you look closely at Christina's World, is really rich and, with a nod to the last post in this series, pied. The ugliness of the land is redeemed in the eye of Wyeth.

Let us now look at Christina, the woman in the picture. Upon first glance the scene looks romantic. A woman appears to be lounging and gazing wistfully at the farmhouse. The scene seems peaceful and relaxed.

But nothing could be further from the truth. Christina Olson, the woman in the painting, suffered from muscular degeneration, probably polio, that paralyzed her lower body. You can see this in the painting by looking closely at Christina's right arm. Consequently, Christina is looking back at the farmhouse, not with relaxation, but with a bit of dread and fatigue. Christina has drug herself out to the garden to pick vegetables and now, very tired, has to face the prospect of dragging herself across the ground back to the house. This is Christina's world.

How are we to look at Christina's World? On the one hand the painting is spiritual, beautiful, romantic, and peaceful. But on the other hand the painting is brutally physical, difficult, tragic, and full of struggle.

Obviously, this dual perspective is the genius of Christina's World. As Wyeth has said of the painting and of Christina, Christina "was limited physically but by no means spiritually." Thus, "The challenge to me was to do justice to her extraordinary conquest of a life which most people would consider hopeless."

Christina's world is our world. On the one hand it is tragic, difficult, and ugly. But if we have the eyes of God, as Wyeth did, a wholly other perspective opens up to us.

Into the World--Chapter Two: The Layered Gospel Context

Contents

Contents

Prologue and Abstract

Chapter One: Introduction

Chapter Two: The Layered Gospel Context

Chapter Three: Today’s Warring Intellectual Context

Chapter Four: A Perpetual Warring Intellectual Context

Chapter Five: A Primer—The Bible’s Broadest Theme

Chapter Six: The Voice of Conscience

Chapter Seven: The Voice of God

Chapter Eight: The Message of the Cross as Supreme Answer

Chapter Nine: The View from Enlightened Self-Interest

Chapter Ten: The Challenge from Kantian Autonomy

Chapter Eleven: The View from James’ Radical Question

Chapter Twelve: The View from Sartre’s Bad Faith

Chapter Thirteen: Kierkegaard’s Challenge to Intelligibility—First Part

Chapter Thirteen: Kierkegaard’s Challenge to Intelligibility—Second Part

Epilogue

There are many ways to view the passage leading to, containing, and immediately following Pilate’s famous question. (John 18:1-19:16) But is there a central theme, idea, or purpose to which it can be tied?

To begin, note that Jesus prompted Pilate’s question. In response to queries from Pilate—as to whether he was the King of the Jews and why he had been arrested—Jesus said, “My kingdom is not from this world. …” To that statement Pilate sensibly inquired, “So you are a king?” The text of the Gospel reads, “Jesus answered, ‘You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.’” (John 18:36, 37)

Pilate’s “What is truth?” follows. To recap, one can be forgiven, I hope, for thinking that it is a good question, given the immediate context. Indeed, it reeks irony that Jesus did not take the opportunity to testify about “the truth,” since he claimed that very thing as his life’s purpose. Nor can we simply excuse The Gospel According to John for Jesus’ silence following Pilate’s question on the grounds that Pilate chose to walk out on Jesus rather than wait for an answer. For as we have seen, Scripture’s seeming general silence in providing an answer to Pilate’s questions is—if anything—even more troubling, and that silence can not be so easily dismissed.

Earlier in Chapter 18 of the Gospel Jesus replies to questions from his arrestors about his ministry, saying, “I have spoken openly to the world; I have always taught in the synagogues and in the temple, where all the Jews come together. I have said nothing in secret. Why do you ask me?” Having just been arrested, the point of Jesus’ comments is obvious. His arrestors should have known why they had arrested him. For making his comments, however, “one of the police standing nearby struck Jesus on the face.” The larger context of Jesus’ arrest, then, provides a vivid rationale for any reticence he displayed. (John 18:19-24) Furthermore, it seems to indicate that the answers we seek will be recorded elsewhere, if we only look—though that rings false with reference to the famous question at hand.

But again a further layer of context places the exchange in a different light. We return to the enigmatic remarks made after Pilate asked Jesus, “So you are a king?” First Jesus said, “You say that I am a king.” (John 18:37) The reply seems evasive, since Jesus prompted the question. Now an evasive reply can be an attempt to avoid truth, in which case it can be seen as a form of dishonesty, the opposite of truth. The text, however, does not support that interpretation. Jesus’ comment about his kingdom was that it “is not from this world.” (John 18:36) Thus, the words rebut the intended thrust of the accusation, which the accusers pressed against Pilate later in the text: “‘… Everyone who claims to be a king sets himself against the emperor.’”1 (John 19:12)

Further, the remark indicates that Jesus did not advance the claim to be a king, an important point, if he was to be seen as a threat to the emperor. Rather, his accusers advanced the claim. Given this fuller context, then, the implication is that Jesus would not have come to the attention of Pilate as a rival of Rome, because he was not advancing a claim to kingship in a way that would threaten the emperor.

From this perspective, the correct move for a person seeking jurisprudence would have been to see whether the accusers in turn had credible evidence to rebut Jesus’ words. That was the business at hand, and Pilate chose—instead—to ask the famous question. So now it is Pilate who seems evasive. Does this observation excuse Jesus once again, and at a deeper level of textual analysis? We must sort through the many layers of point and counterpoint embedded in the text before rendering our judgment.

Adding the next layer, since Jesus prompted the question, fairness to Pilate (as a character in the text) requires us to ask whether he had any justification for turning from the judicial question at hand to a philosophical one. Again, Jesus said, “For this I was born; and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.” (John 18:37) A miniature philosophy lesson will be helpful here.

“Truth” is a common noun. It shares that status with a great many other words, such as “dog” and “circle.” And as the words “dog” and “circle” have clear applications to objects of reference most of the time, so does “truth.” Accordingly, to ask what the truth is in a particular instance—say, whether it is true that Spot is a dog for someone familiar with a particular barking, tail-wagging companion named “Spot”—is almost always a matter beneath serious consideration. But as an educated man, Pilate may well have known philosophy, or perhaps been influenced by the opinions of persons who did. And for a philosopher in Pilate’s day, the conceptual standing of a common noun—especially one as near to the heart of philosophy as “truth”—will have been an important point to consider.

Plato’s “doctrine of recollection” was (and may still be) the most famous account of how we are able to understand the meaning of common nouns—such as “truth,” “dog,” or “circle.”2 It held that human souls identify kinds of objects in this world by a recalling their ideal forms. Basically, objects in our world are imperfect copies of their eternal forms, and our souls, which Plato believed are eternal, “recall” the eternal forms to use as exemplars for the purpose of making judgments about objects in our world. Plato’s Meno provides a rationale for this view. And it informs his famous “allegory of the cave” from The Republic.

This aspect of Platonism influenced Western thought so heavily that through the Middle Ages to be a realist meant to believe in the reality of these eternal forms, in one philosophical or religious version or another. More significantly, this view influenced the early Christian Church heavily too. For one thing, it contributed to the philosophical perspective behind Gnosticism, Christianity’s first “heresy.”3 In part, Gnosticism arose within Christianity because one cannot believe both that objects in this world are imperfect copies of eternal forms from beyond this world and that Jesus was God incarnate who really came “into the world.” Nevertheless, it is plain that the Platonic view bears on the remarks that prompted Pilate’s question. Did John's Jesus mean to say that he came into the world to bear testimony to eternal truth in a way that could be compared with the teaching of philosophical schools with which Pilate may well have been familiar? If so, Jesus—not Pilate—shifted the focus from jurisprudence to philosophy.

Furthermore, it is clear that Pilate was not friendly toward those who had arrested Jesus, and the text also makes it clear that he saw no substance in the charge brought by the accusers. It seems possible, then, that he hoped to have an erudite conversation with Jesus; that he hoped to find in Jesus a fellow sophisticate with whom he could strike an understanding against the accusers.

On this supposition, had the accusers complained to Rome that Pilate did not crucify this man who set himself against the emperor, Pilate could have produced a cultured, urbane man who was too much of a sophist to be a leader of zealots. Of course this is only a speculation, albeit one that the text leaves open. On the other hand Pilate may have scorned Jesus and his comments along with the accusers, just as Nietzsche claimed (though with unjustified confidence). One cannot say more on the point, since the text does not intimate Pilate’s thoughts to us.

A small feature of Jesus' statement, however, should jump out at us: the word “the.” For use of the definite article (in contrast to the indefinite article, “a,” or a usage which excludes the use of an article) indicates that what follows “the” is understood. The question that should animate us, then, is “Was there a definite truth that Jesus could presume that Pilate would understand him to mean?”

We find a possibility by viewing yet another facet of the context surrounding the famous question. The accusers arrested Jesus not as a threat to the emperor, but as a man whom they claimed violated Jewish religious law. In trying to release Jesus, Pilate was confronted with the fact that the accusers were intent on seeking Jesus’ death: “We have a law, and according to that law he ought to die because he has claimed to be the Son of God.” (John 19:7)

(In passing we can note the slipshod deal that the accusers were trying to force on Pilate—to find Jesus guilty according to Roman law so that they could have him crucified for breaking a Jewish religious law.)

Accordingly, the possibility that Jesus might have expected Pilate to know is that his claim to be the Son of God would explain his relationship to “the truth.” This contextual layer raises an especially strong point of view because it merges the philosophical aspects of the text with the actual charge for which Jesus’ accusers wanted him put to death.

The charge, “he has claimed to be the Son of God,” animated the accusers. It also informed the comment that prompted Pilate’s question, “For this…I came into the world, to testify to the truth.” In Platonic terms we would interpret Jesus’ coming “into the world” to mean this: The eternal, exemplary Son of God came into the world to give us direct testimony to “the truth” about God.

Is this the definitive perspective on the exchange, or is it just one more layer of context? The Prologue of The Gospel answers that question explicitly:

"In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came in to being. …grace and truth came through Jesus Christ. No one has ever seen God. It is God the only Son, who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known." (John 1:1-3; 17, 18)

“Word” in this text is a translation of “Logos,” which to the Ancient Greeks and Romans meant the divine ordering principle of the world.4 The Prologue sets the context of Pilate’s interaction with Jesus in the broadest possible sense, then, and not only for interpreting the text of the Gospel itself, but for interpreting the text’s theological and philosophical implications. Accordingly, we can be sure that we are to read the philosophical implications into the text of Jesus’ dialog with Pilate.

“The truth” that Jesus illumines, according to the full context of The Gospel According to John, is undoubtedly the truth about God.

Yet in a sense the problem of interpreting the text just got far more difficult. For “the truth” about God does not look at all like what we expect the truth about God to be. “Here is the man!” said Pilate, bringing Jesus out for the accusers to see. “Crucify him! Crucify him!” they cried. (John 19:5, 6) To be subject to human judgment and condemnation could not be further from God conceived as the “Supreme Being,” or as the “Almighty,” or as “Lord,” or as the Being “than whom none greater can be conceived,” or indeed as divine “Word”—the “Logos”—the divine ordering principle of the world. The view of God that the text of The Gospel According to John opens to the reader, then, is God as Supreme Irony, not God as Supreme Being. If one seeks to understand “the truth” about God through Jesus, what does one make of that?

The central point must become this, for there is no other way out if there is to be any hope of an answer: We must ascribe the irony to ourselves, not the text. Why? Because the truth about God in the Gospel is represented by a man about to be crucified! And if we give that representation hypothetical status as “the truth” about God for the purposes of trying to understand it, we are left to assume that it is our view of God that produces the irony, not the text itself, which again, ex hypothesi, depicts the truth. In short, either we create the Supreme Irony by our false view of God, or there is no coherent way to view the text as representing the truth about God.

In short, belief that Jesus is the divine Logos, the Word of God, would provide the correct view of God to those who believe.

On this hypothesis, the main thrust of the Gospel message is to reform our false view of God by giving us Jesus’ testimony to the truth. But this immediately confronts us with a challenge: Jesus—God incarnate, Logos, “Christ,”—standing before a judge deciding whether to have him killed, allowed his interrogator to walk out on him at the very point that he could formally fulfill his life's mission of testifying to the truth about God. And here the irony certainly is embedded in the text as a glaring challenge to the reader. (To make sense of the text, one must obviously enough act on the assumption that the text makes sense.) We address that irony by asking how Jesus’ silence at that crucial moment depicts divinity. We will not press that question yet, but it will, of course, form the centerpiece of the grand perspective to be gained—the mountain’s peak whose successive levels we are forming by adding contextual layers to our understanding of the core text.

It would have been a cheap trick to begin by quoting the Prologue of The Gospel According to John in order to say that Jesus is the Word of God made flesh according to the text, and therefore, his silence in the face of Pilate’s question is the de facto expressed “testimony” of the Word of God. But having examined the faceted context surrounding Pilate’s famous question, we are led back to that very assertion. It is as though the Prologue was placed at the head of the text of the Gospel to make sure that we don’t miss its central point, the crux of Christian faith, that the Supreme Being came into the world as the Supreme Irony to teach us the truth about God. And yet, what precisely is that truth, that central point, that we should see?! And how does it correct our false view of God?

CHAPTER TWO NOTES

1. A king whose kingdom is not of this world does not set himself against an emperor whose reign is of this world.

2. For a good overview see Frederick Copleston’s chapter on Plato’s doctrine of forms in Volume I of his A History of Philosophy (Image, 1962).

3. For a good overview see the second chapter of Paul Tillich’s A History of Christian Thought (Simon and Schuster, 1967).

4. Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Tenth Ed., 1996.

The Varieties of Love and Hate

Thanks for all the interesting conversation that is still ongoing about the What is the Opposite of Love? poll and post.

Thanks for all the interesting conversation that is still ongoing about the What is the Opposite of Love? poll and post.

That conversation had me thinking hard about the relationships between love, hate, and apathy.

As a psychologist I like to think in models, so I created a model. I initially sketched out the interrelationships between love, hate and apathy like this:

I don't think "apathos" is a word. I just made that up. But basically, if you noticed, I pulled my thinking from my comments in the Opposite of Love post into this diagram. First, there is the "apathy" dimension, where our actions can be intense, engaged, and "hot" (pathos) versus when our actions are cooler, more disengaged, and distant (apathos). The vertical dimension charts our antisocial versus prosocial impulses. This dimension gets at Augustine's incurvatus in se (i.e., antisocial: the self "curved in on itself") as opposed to an excurvatus ex se (i.e., prosocial: a self curved outward).

Thus we have cold froms of hate like apartheid, segregation, and abandonment. This is the hate Chris was referring to (I think). Similarly, there are hotter forms of hate like genocide, hate crimes, and malicioius violence. This was the hate I was talking about.

In a similar way there are cooler and distant forms of prosocialness, like charity and tolerance. Hotter forms of prosocialness are social justice, solidarity and advocacy.

One of the points I was making in the last post was that the reason I thought that the "apathy is the opposite of love" formulation became so dominant was that preachers generally found their churches in the "charity quadrant." The congregations loved, but coolly and distantly. Thus, to call them to greater love the only move to make is to work the apathy dimension, moving a cool love into a more passionate engagement with the world.

After sketching this model I went in search of a better theological framework. As suggested by Daniel, I went to Miroslav Volf's Exclusion and Embrace. Using some of Volf's categories I reworked the model into the following:

As you can see, I replace prosocial with embrace and antisocial with exclusion. I reframe the horizontal dimension as active versus passive. Consequently, we see Volf's discussion of abandonment as a form, a passive form, of exclusion (Volf makes this point). And, as Volf also notes, a more active form of exclusion is elimination (e.g., genocide).

We find the words "contract" versus "covenant" in the top two quadrants. Again, these are Volf's terms. Contract here is the agreed upon social contracts that govern peaceable human community. Volf notes that this is a form of embrace, but that it falls well short of what God calls us to. Love is more than living civilly, although that is a necessary prerequisite. Thus, Volf calls the church away from framing her relationships with the Other through politics and social agreements. Replacing contract should be covenant, the loving and passionate engagement (hesed) that God models for us as he remains faithful to His people.

Finally, as I reflected on all this, I noted a flow moving through the quadrants:

That is, if you are in quadrant i--elimination--it would be difficult to move you into quadrant iv directly. Rather, you'd probably have to move through each quadrant in a clockwise direction. As a data point in support of this model we can note that America moved through the quadrants in roughly that order:

Slavery to Segregation to Civil Rights to ....

We are still working on the final movement. And perhaps forever will be. We still dream...

God is always happy...even if a hammer falls on his head.

A backseat conversation between my two sons overheard by their mother on the way to school today:

A backseat conversation between my two sons overheard by their mother on the way to school today:

Aidan (the youngest): "When we are in heaven is God always happy?"

Brenden (the oldest, and who also speaks with the theological authority of the Church Fathers): "Yes, God is always happy."

Aidan: "Always???"

Brenden: "In heaven God is always happy."

Aidan: "Even if a hammer fell on his head?"

Brenden (thoughtfully): "Well, since God knows everything that is going to happen before it happens, I figure He would dodge it."

Aidan: "Yeah, you're right."

The Opposite of Love Is...

Would you like to weigh in on a little debate I’m having here on campus?

Would you like to weigh in on a little debate I’m having here on campus?

Here’s the question: What is the opposite of love?

Recently, I was discussing faith and life with a group of students along with a colleague from the College of Biblical Studies. During the discussion my colleague floated the very common formulation about love’s opposite. Specifically, he said:

“The opposite of love is not hate, it is apathy.”

I pondered that line and this week, while leading my bible class at church, publicly disagreed with it. I said something like this:

“The line you frequently hear in church is that ‘the opposite of love is not hate but apathy.’ But that’s just crazy. The opposite of love IS hate. Hate is way worse than apathy.”

Afterwards, my friend Chris, also from our College of Biblical Studies, defended the “the opposite of love is apathy” formulation. Chris’ basic contention was this:

Apathy, at its core, doesn’t even grant your existence. That is, your basic existence is not noted or recognized as worth even the most basic or moral consideration; you are, at root, “nothing,” a non-entity. Chris considered this “denial of existence” to be worse than hate and, thus, worthy of being accorded the status of “the opposite of love.”

I disagreed. True, a failure to recognize (morally speaking) the existence of the Other is a deep failure of love. But hate, at its core, seeks the non-existence of the Other, it seeks the eradication of the Other. Hate is more than holding that you don’t exist; hate contends that you don’t deserve existence, that existence should be taken from you. Hate, as I understand it, sits behind racism, lynching, and genocide. Hate is much more than apathy, it is active and morally justified (to the perpetrators) violence. I see this as much worse than apathy and, thus, place hate as “the opposite of love.”

Don’t get me wrong, apathy, as I said, is a very deep and tragic failure of love and a form of violence, but I’m sticking with hate as the true “opposite.”

So what do you think? Is Chris right? Or me? Cast your vote and I’ll let you decide:

This silliness aside, let me spend a moment reflecting on a more interesting issue associated with the “opposite of love” debate. Specifically, why is the “apathy is the opposite of love” formulation so widespread and commonplace?

Here’s what I think happened. I’ve long argued that since the Axial Age and the Enlightenment humans have, on average, particularly in nations affected by the Enlightenment, grown more moral. Charles Taylor in his book The Secular Age makes a similar argument, noting that the reforming influence in Latin Christianity led to a great emphasis on “civilizing” the masses. Public education comes to mind. By and large, although I recognize the glaring exceptions, humanistic values have taken hold in the world. The point is, hate isn’t rampant in our pews. Preachers generally don’t face genocidal audiences. What they do face are nice people. Tolerant and politically correct people.

Consequently, thundering on about hate isn’t very useful, rhetorically speaking. Hate just doesn’t speak to the moral experience of the average person in the pew.

But what does speak to the pressing moral issue in most churches is apathy. Nice people don’t need to hear sermons about hate. But they do need to hear sermons about apathy. Apathy sermons gain some rhetorical leverage on the average church audience. So, the love/hate dichotomy got reworked into the love/apathy dichotomy to make sermons more rhetorically powerful. In short, I believe that the “apathy is the opposite of love” formulation now dominates, not because it is true, but because it is rhetorically useful.

If this analysis holds it’s an interesting observation in that it suggests that popular theology is often driven less by concerns about validity than about efficacy. Personally, I think it is this dynamic (efficacy over validity) that has led to the ascendance of penal substitutionary atonement. Specifically, the penal substitutionary metaphors made for the most rhetorically powerful sermons and, as a result, led to the soteriological biases and abuses we see today. In short, the emotional connection between preacher and congregation is a source of theological pressure which nudges theological discourse in different directions.

Ugly: Part 6, Pied Beauty

In my most recent church class on Ugly my dear friend Sherry, one of the most admired English professors at the school, walked us through her insights into the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889).

In my most recent church class on Ugly my dear friend Sherry, one of the most admired English professors at the school, walked us through her insights into the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889).

Hopkins was a Jesuit priest and is now considered one of the most significant Victorian-era poets. But this recognition came many years after Hopkins' death. Hopkins' poems, perhaps too innovative during his lifetime, became noteworthy later on for his innovations in imagery, rhyme, wordplay, and meter.

The Hopkins poem we spent most of our time on is entitled Pied Beauty. It might be helpful to know that "pied" is an old word for speckled, splotched, or multicolored things:

Pied Beauty

Glory be to God for dappled things—

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced—fold, fallow, and plough;

And all trades, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

Many reflections were shared in class about this wonderful poem. What follows are some of mine.

What I like about this poem is how it calls us to a "generous aesthetic" (echoing a "generous orthodoxy"). That is, we generally don't find beauty in splotched, freckled, blotched, speckled, motley, stippled, flecked, and blotted things. Hopkins calls us to see the "counter" and "strange" as beautiful. Not just the sweet but also sour is to be seen as wondrous.

As I think about Pied Beauty I wonder if Hopkins is not simply asking us to see the beauty in our pied surroundings; I wonder if he is also speaking metaphorically about human affairs. About how we see the counter, strange, slow, and sour people around us. And I also wonder if Hopkins is not wondering about our pied souls and lives. We are original, counter, fickle, and freckled. Our hearts dance with light and dark, sunlight and shadow, joy and sorrow, saintliness and sinfulness. To be human is to be pied. And there is a homely and honest beauty, if somewhat of a mixed-up sort, in the human experience.

That which is pied, obviously, isn't necessarily or typically ugly. But living life with eyes for pied beauty, in creation and in our social sphere, is at the heart of what I'm hoping to call us to in this series. A call to living life with a "generous aesthetic," a hopeful curiosity and expectation that beauty is to be found in the most mundane and unexpected of places.

Into the World--Chapter One: Introduction

Contents

Contents

Prologue and Abstract

Chapter One: Introduction

Chapter Two: The Layered Gospel Context

Chapter Three: Today’s Warring Intellectual Context

Chapter Four: A Perpetual Warring Intellectual Context

Chapter Five: A Primer—The Bible’s Broadest Theme

Chapter Six: The Voice of Conscience

Chapter Seven: The Voice of God

Chapter Eight: The Message of the Cross as Supreme Answer

Chapter Nine: The View from Enlightened Self-Interest

Chapter Ten: The Challenge from Kantian Autonomy

Chapter Eleven: The View from James’ Radical Question

Chapter Twelve: The View from Sartre’s Bad Faith

Chapter Thirteen: Kierkegaard’s Challenge to Intelligibility—First Part

Chapter Thirteen: Kierkegaard’s Challenge to Intelligibility—Second Part

Epilogue

“‘… For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.’ Pilate asked him, ‘What is truth?’”

John 18: 36-37

Is there a graver, more searching challenge to Christian faith than the one posed by Nietzsche concerning the exchange (quoted above) between Jesus and Pilate in Chapter 18 of The Gospel According to John? About Pilate’s famous question Nietzsche wrote that it is the “annihilation” of the New Testament.1 Reduced to its components, Jesus’ exchange with Pilate (above) contains (1) Jesus’ portentous claim to have come “into the world to testify to the truth” followed by (2) Pilate’s request for Jesus to testify to the meaning of truth; then (3) silence. Walking in on such an exchange—as posed—one would likely suspect that it had exposed a charlatan. Occurring in a book written to support the portentous claim (John 20: 30-31), one may well suspect that the text commits a monumental faux pas. Did this seemingly scandalous silence motivate Nietzsche’s comment on the exchange in The Antichrist?:

“The noble scorn of a Roman confronted with an impudent abuse of the word ‘truth,’ has enriched the New Testament with the only saying that has value—one which is its criticism, even its annihilation, ‘What is truth?’”2

There is a problem with pinning Nietzsche’s comment to the seeming faux pas. Pilate “does not wait for an answer,”3 a view the Phillips translation makes clear: “…Pilate retorted, ‘What is truth?’ and went straight out…”4 That simple addition turns a scene in which Jesus looks like a charlatan into one in which Pilate looks impatient and imperious before a man the text identifies as the divine Logos. (Talk about “impudence!”) Moreover, if those who belong to the truth listen to Jesus’ voice, Pilate enacted judgment on himself by not waiting for Jesus’ reply. There can be no doubt that the author of The Gospel According to John intended to convey the irony of Jesus’ judge bringing judgment on himself as he enacted judgment on Jesus: As we will see, this and other ironies are used throughout the Johaninne passion narrative to maintain a consistent portrayal of Jesus as the divine Logos.5

But this second pass also proves misleading. A gifted philologist, Nietzsche would have been unlikely to have overlooked the intended irony. Thus, it makes sense to look for other grounds specific to his disdain of Jesus’ grand claim—grounds that align him with the scornful attitude toward an “impudent abuse of the word ‘truth’” that he assigns to Pilate. In Concerning Truth and Falsehood in an Extramoral Sense Nietzsche identifies precisely the needed grounds:

"Truths are illusions which we have forgotten are illusions, worn out metaphors now impotent to stir the senses, coins which have lost their faces and are considered now as metal rather than currency."6

The application is clear: If truths are illusions, the Jesus of The Gospel According to John was deluded.

Thus, for those who share Nietzsche’s point of view, the Johannine narrative still commits a monumental faux pas: The grand claim becomes an artifact of a philosophical naivete that makes Jesus once again look like a charlatan. But this time Pilate’s failure to listen has no bearing on the appraisal. Moreover, the Gospel commits the same faux pas elsewhere (John 1:9; 14:6). Yet Scripture seems silent throughout about what the claim means, unless one accepts the Prologue of the Gospel as a contextual explanation, that Jesus is the divine Logos (John 1:1-18). For a modern skeptic, however, that contextual “explanation” only makes things worse.

Before noting why, two rhetorical gambits should be avoided. First, asking whether Nietzsche’s view that “Truths are illusions” is truer than Jesus’ claim to have come “into the world to testify to the truth,” and second, asking whether a statement attributed to the divine Logos might be taken as seriously as Nietzsche’s opinion. A brief consideration of what Nietzsche meant shows that such comments miss the point.

Nietzsche disparaged metaphysical truths—views of truth that attempt to connect it to realities beyond the mundane world, such as the realm of Platonic ideas or, more directly to the portentous claim that inspired Pilate’s famous question, the divine Logos. In the same breath it is important to note that he did not deny ordinary practical truths of a kind that everyone is familiar with. For example, that a whole is equal to the sum of its parts or that it is true for me now that I am writing these words on Monday, January 28. Being a truth of reason and a matter of fact, respectively, such mundane “truths” require no grounding outside of human experience to understand.7 Accordingly, what Nietzsche denied is that there is any kind of truth grounded in a deeper or higher or more enlightened perspective than is available to human beings who are investigating this world. Bluntly, he denied that there is any grand truth that requires a divine Logos to come “into the world” to reveal it. That is the rationale behind Nietzsche’s venomous comment.

Nietzsche’s dismissal of metaphysical truth was, and still is, common. The most famous example may be Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which opens in direct counterpoint to Jesus’ grand claim to have come “into the world to testify to the truth.” The Tractatus opens, “The world is all that is the case.”8 Though Wittgenstein later abandoned this perspective, his opening words in the Tractatus still speak for many intellectuals.9

A brief explanation will help. Written to mark the boundary of meaningful discourse, entry “into the world” of the Tractatus requires one to form a logically coherent description of “a possible situation.”9 Following that, “The agreement or disagreement of its sense [its description of a possible situation] with reality constitutes its truth or falsity.”10 The gist of the Tractatus, then, is this: All meaningful "truths" can be given definite descriptions which can then—at least in theory—be tested against the “reality” of this world. Though I share the view from neither The Antichrist nor the Tractatus, I do think that if a man speaks of having come “into the world to testify to the truth” that an explanation should be forthcoming, and no amount of ironic plot intervention can alter that. Admittedly, that Pilate walked out on Jesus before he could respond may have prevented Jesus, at that juncture in the narrative, from testifying to the truth (though even that is questionable, given who the Gospel tells us Pilate was walking out on!).

Be that as it may, the Gospel purportedly records Jesus’ teachings, and that makes it extremely odd that if his life purpose was to come “into the world to testify to the truth,” that the truth to which he came to testify is nowhere directly explained or defined. The larger point can be stated very simply: Jesus’ grand claim sounds philosophical, but philosophical explanations are nowhere to be found in the Gospel, the New Testament, or the Bible.

Nor will it work to say that the author of John did not intend to make a philosophical point with Jesus’ words. Written at a time when Stoicism and Neo-Platonism would have leant considerable prestige to Jesus’ claim, the Gospel could have used it to good effect. But the intervening 2,000 years have exposed—even burlesqued—grand metaphysical claims as empty in the eyes of many intellectuals. For many today it is science which informs our “higher” understanding of truth, and science borrows no meanings from religious or metaphysical speculations. In short, a modern intellectual might well be expected to respond to Jesus’ claim just as the Phillips translation depicts Pilate to have done. Again, “…Pilate retorted, ‘What is truth?’ and went straight out…” Nietzsche was clearly correct in this sense: The scene of the exchange between Jesus and Pilate can be seen to depict the same dismissive attitude toward religious and metaphysical claims that one expects from many intellectuals today.

In a sense we have arrived again where our first reading left us: Jesus’ portentous claim followed by Pilate’s question followed by a silence which suggests a charlatan. Of course now we understand the “silence” as a historically-rendered void that a metaphysically-informed religious meaning used to fill. For in spite of the fact that the text presents us with an exculpatory irony in Pilate’s failure to listen to Jesus, the culpability remains at a deeper level. In that case Scripture’s culpable silence in response to Pilate’s famous question can be seen to remain, and Jesus as the divine Logos who came “into the world to testify to the truth” remains the object of that culpability for that silence. Thus, the famous exchange between Pilate and Jesus can still be viewed as a scene that depicts a monumental faux pas by way of Jesus’ silence.

Or does it? In fact the purpose of these posts is to argue that Scripture does respond, and that the response possesses an amazing depth and credibility--a depth and credibility that is focused in the Johannine trial scene. The purpose of this introduction, then, is to frame the skeptical point of view to which, in fact, Scripture provides a counterpoint.

In stark contradistinction to Nietzsche’s perspective on the exchange, these posts will show that a careful examination of the Gospel text, in light of a full biblical context, reveals not only an answer to Pilate’s famous question, but to what William James called “the radical question of life.”12 Ironically, the “answer” is embedded in the very passion narrative from which the exchange with Pilate is taken. As shall come to light, to speak of Jesus as the truth is to say that the passion narrative portrays the answer to the core question of what it means to be a human being. That is, Scripture presents Jesus as the true revelation of ourselves to ourselves.13

CHAPTER ONE NOTES

1. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Antichrist, Passage 46, tr. Walter Kaufmann, in The Portable Nietzsche, (Penguin Books, New York, 1982) p. 627.

2. Ibid.

3. R. Alan Culpepper, Anatomy of the Fourth Gospel, (Fortress Press, Philadelphia, 1983) p. 142. (I would have missed this point, if not for Dr. Culpepper’s help.)

4. The New Testament in Modern English, tr. J. B. Phillips, (Copyright © The Macmillan Company 1952, 1957).

5. Chapters Six and Seven.

6. Friedrich Nietzsche, tr. Arthur C. Danto, in Arthur C. Danto, Nietzsche as Philosopher, (Columbia University Press, New York, 1965) p. 39.

7. “Truths of reason” and “matters of fact” derive from the famous passage that ends David Hume’s An Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding, ed. Charles W. Hendel (Macmillian Publishing Company, New York, 1989): “If we take in our hand any volume—of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance—let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames, for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.” (p. 173)

8. Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, tr. D. F. Pears and B. F. McGuinness,(Humanities Press International, Atlantic Highlands, 1974) p. 5.

9. “For since beginning to occupy myself with philosophy again, sixteen years ago, I have been forced to admit mistakes in what I wrote in that first book [the Tractatus].” Wittgenstein in his preface to Philosophical Investigations, Third Ed., tr. G. E. M. Anscombe, (Prentice Hall,Englewood Cliffs, 1958) p. vi.

10. Chapter 6 of Kenneth R. Miller’s Finding Darwin’s God contains a good discussion of scientific reductionism as it is held by some notable scientists today and pitted against religious belief. (HarperCollins, New York, 1999).

11. Tractatus, p. 10.

12. Ibid.

13. William James, “The Sentiment of Rationality,” in The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy, (Dover, New York, 1956) p. 103.

14. It is common for Christians to argue against a reductive view of truth (for instance, But Is It All True? The Bible and the Question of Truth, ed. Alan G. Padgett and Patrick R. Keifert, (William B. Eerdmann’s Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, 2006)). What Into the World argues for is a more definite understanding of the truth to which Jesus’ life witnessed.

Into the World--Prologue and Abstract

Prologue

Upon hearing me explain that I decided not to go to seminary because I had too many unresolved questions a pastor friend recently replied, "I was too smart to get tangled up with those questions." We let the foot-in-mouth remark pass, as was appropriate in friendly conversation. Yet it illustrates an all too common assumption that this series of posts on Richard's blog seeks to challenge and set right: that faith and skepticism are antonyms.

It is my hope to confront Christian anti-intellectualism by illustrating that skepticism at its greatest depth can lead to an understanding of faith at its greatest height. In fact, I see the relationship between the two as like the relationship of a mountain to its accompanying lowlands, without which the mountain would not be. Accordingly, I have placed the most trenchant criticism of Christian faith that I know of at the beginning of these posts: Nietzsche's comment on the exchange between Jesus and Pilate in The Gospel According to John--the exchange which led to the question, "What is truth?"

Abstract

Concerning Pilate's famous question, "What is truth?" Scripture is silent throughout on a philosophical level. That categorical silence seems scandalous, since Jesus' metaphysical claim to have come "into the world to testify to the truth" prompted the question. Analysis of the full biblical context, however, reveals the opposite: The passion story does protray an answer to Pilate's question, as well as to what William James called "the radical question of life." Chapters one through seven focus primarily on the biblical context; chapters eight through thirteen provide a conceptual context to frame the biblical.

Into the World--Guest Author Introduction

If you are a regular reader here you may remember about a year ago when Tracy Witham contributed a wonderful guest piece associated with my series on William James. You probably also know that Tracy is a consistent and insightful commenter here at Experimental Theology.

Some weeks ago Tracy asked me if he might share this space, allowing him to share some of his intellectual and theological work with you, a book he has been working on. I was very pleased to agree as the themes Tracy reflects on converge on my own interests in this blog. Consequently, in the coming weeks you'll see Tracy's installments come out on or around Friday of each week. To let you get to know our guest writer a bit I asked Tracy to introduce himself in this post to accompany the first installment of his book.

I'm looking forward to this series and the conversation that surrounds it.

Best,

Richard

Dear Reader,

It is a gracious and generous act of kindness on Richard's part to share this blog space with me--truly an act of hospitality! Many times I have wished that I could applaud his daring choice of topics, his insights, the playfulness he brings to difficult ideas, and his skill as an on-line teacher. And always I am amazed at the sheer speed with which he reads, assimilates, and writes about new topics. It is an honor and a privelege that I do not take lightly to be a guest writier on his blog.

Thoreau explained his experiment at Walden by writing some of the most famous words in American literature. “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I had come to die, discover that I had not lived.” I use that sentence as if it were Scripture; that is, I use it as a means to shed telling light on my soul and the souls of others.

My life—and I suspect yours too—is cluttered over with details that detract more than they contribute to an understanding of who I am. The exceptions are found where the facts inform my woods—my Waldens; those places where I have gone following deliberations which have aligned my life with the passions that illuminate my soul.

A minor character in A Few Good Men explained how he knew what to do without being told by saying, “I just followed the crowd at lunchtime.” It is possible to follow the crowd at lunchtime and breakfast-time and dinner too. And if one makes a habit of it, it just might be possible to discover, when one comes to die, that no real human life has emerged from one’s human being.

Don’t get me wrong. It is entirely possible to find delight in the crowd and to passionately choose others as one’s Walden. In fact, to say that that has not been possible for me entails that I am a deeply flawed Christian—though to be fair, that is a tautology. (I think I hear Nietzsche laughing, and I hope he can hear me laugh with him.)

“Two roads diverged in a wood, and I--I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference.” These famous words fail to express the infinite tertium quid of Thoreau’s famous “sauntering” around the woods of Walden—an activity that can make all the rest of the difference for those of us who see life as rather more differentiated than Frost’s poem suggests. Twenty-five years ago I decided not to go to seminary, but to follow my nose into the thicket of questions surrounding faith. Some might say that I got lost. I say, "That has been my Walden."

I introduce myself, then, as an intellectual saunterer who, like Richard and you his readers, is passionate about exploring the Christian theological and religious landscape. That is a Walden we share, which means that there is already a sense in which you know me. Beyond that you can think of me as being a bit like the shepherd who—the story goes—threw a rock in a cave and discovered the Dead Sea scrolls. For I have wandered a bit and thrown a few rocks and happened upon something that I think will interest you.

Ugly: Part 5, The Isenheim Altarpiece

In the last post we left with the question: Why the cross? Why is ugliness at the heart of the Christian faith?

In the last post we left with the question: Why the cross? Why is ugliness at the heart of the Christian faith?

Perhaps one answer comes to us from the Isenheim Altarpiece.

The Isenheim Altarpiece was painted by Matthias Grünewald some time between 1512 and 1516 for the Monastery of St. Anthony in Isenheim (then in Germany). This complicated work of multiple panels depicts four biblical scenes, the Annunciation, the Crucifixion, the Lamentation, and the Resurrection. The first view of the altarpiece is of the Crucifixion (upper panels) and the Lamentation (lower panels). The Crucifixion panels are by far the most famous aspect of the altarpiece:

The Grünewald Crucifixion is considered to be one of the most horrific and painful crucifixions ever painted. Perhaps more horrific crucifixions have been painted since the Isenheim Altarpiece, but relative to the genres of its time (and even today) the Grünewald Crucifixion remains unique in the risks it took. But more than this, the fame of the Isenheim Altarpiece is largely due to the fact that this Crucifixion scene was used in a church. Rarely if ever has a scene of such graphic horror been used regularly as the central image of a worship space.

To come to grips with the Grünewald Crucifixion one needs to see aspects of the painting close up. I appreciate Dan letting me use some of the detail images he brought to our class last week. First, a close up of Jesus' body:

One can see the torn flesh with many pieces of thorns or wood embedded in the body from the scourging. Even more difficult is the sickly green coloration that is employed:

The pain and wretchedness of the Grünewald Crucifixion are particlarly notable in the twisted and unnatural position of Jesus' hands and feet:

These are very difficult images. So difficult that we must ask: How could this horrific picture be the central worship image of a church?

The answer to this question comes from noting that the monks at the Monastery of St. Anthony specialized in hospital work, particularly the treatment of ergotism, the gangrenous poisoning known as "Saint Anthony's fire." In ancient times ergotism was largely caused by ingesting a fungus-afflicted rye or cereal. The symptoms of ergotism included the shedding of the outer layers of the skin, edema, and the decay of body tissues which become black, infected, and malodorous. Prior to death the rotting tissue and limbs are lost or amputated. In 857 a contemporary report of St. Anthony's fire described ergotism like this: "a Great plague of swollen blisters consumed the people by a loathsome rot, so that their limbs were loosened and fell off before death."

The theological power of the Isenheim Altarpiece is that Grünewald painted the gangrenous symptoms of ergotism into his crucifixion scene. As the patients of St. Anthony's Monastery worshiped, and a more hideous, ugly and diseased congregation can scarce be imagined, they looked upon the Isenheim Altarpiece and saw a God who suffered with them.

In a fascinating insight, Dan noted for us that when the Crucifixition panels of the Isenheim Altarpiece are opened we notice the following. In the upper panel, upon opening, the right arm of Jesus is separated from his body. Below the Crucifixion scene in the lower panels depicting the Lamentation the same opening separates the legs of Jesus from his body. In short, as the Isenheim Altarpiece is opened Jesus becomes an amputee, losing an arm and legs. We can only imagine the power of this imagery among a congregation of amputees.

You can see Dan's observation best in the following image. I've highlighted the division in the panels with a bold white line. Again, note how when the panel is opened the right arm (in the upper picture) and the legs (in the lower picture) become detached from the body:

In many ways the Isenheim Altarpiece is the artistic embodiment of my entire theology of ugly. The aesthetic qualities of the Grünewald Crucifixion are ugly, repulsive, and horror-filled. But when we think of this altarpiece sitting in front of the St. Anthony congregation we suddenly see it as beautiful. The painting is horrific because God has entered the horror. The painting is ugly because God became ugly and stood in solidarity with the ugly.

Jurgen Moltmann said it like this in his book The Crucified God:

"The crucified Christ became the brother of the despised, abandoned and oppressed. And this is why brotherhood with the 'least of his brethren' is a necessary part of brotherhood with Christ and identification with him. Thus Christian theology must be worked out amongst these people and with them...in concrete terms amongst and with those who suffer in this society." (p. 24)

"Christian identification with the crucified necessarily brings him into solidarity with the alienated of this world, with the dehumanized and the inhuman." (p. 25)

"The church of the crucified was at first, and basically remains, the church of the oppressed and insulted, the poor and wretched, the church of the people." (p. 52)

And my favorite quote (p. 28, emphases added): "But for the crucified Christ, the prinicple of fellowship is fellowship with those who are different, and solidarity with those who have become alien and have been made different. Its power is not friendship, the love for what is similar and beautiful... but creative love for what is different, alien and ugly..."

Ugly: Part 4, The ugly cross

Sorry for the long time between posts. I've been away taking some very brilliant students to a psychological conference in Kansas City, MO to present our research into the PostSecret phenomenon. Now that the conference is over I feel free to present some of that research here. After this series on Ugly look for some posts on PostSecret.

Sorry for the long time between posts. I've been away taking some very brilliant students to a psychological conference in Kansas City, MO to present our research into the PostSecret phenomenon. Now that the conference is over I feel free to present some of that research here. After this series on Ugly look for some posts on PostSecret.

Now, back to Ugly.

On Wednesday night in my bible class on Ugly I had Dan, one of my good friends, come talk to us about the aesthetics of the crucifixion. Dan is an amazing artist and a wonderful colleague at the University. But what I love most about Dan is his curiosity. You'd think that university profs and academicians are an intellectually curious lot. Not so. Many are specialists, almost technicians, in their narrow area of scholarship. Consequently, few show any interest or desire to read, explore, or dip into areas outside of their speciality. Dan's not like that. His interests, intellectual and spiritual, are polymathic.

In his aesthetics of the crucifixion class Dan initially handed us two artistic portrayals of the crucifixion. The first is an oil on wood done by Raphael in 1505:

The second picture is an oil on canvas done by Lovis Corinth in 1907:

After viewing these two pictures at our tables, Dan asked us to discuss these questions:

Consider the two artworks and answer any of these questions:

Which of these paintings appeals to you most? Why?

Which of these painting would you rather hang in your house? Why?

Which of these paintings do you find to be more reverent or respectful? Why?

Which of these painting is more beautiful? Why?

Which of these paintings is truer? Why?

At my table, as we discussed these questions, we made what are the obvious contrasts. The Raphael painting is a beautiful, peaceful, blue-skied scene. It is suffused with divinity and spirituality.

By contrast, in the Corinth painting there is no trace of the divine. The scene is ugly, grotesque. The nudity is harsh. Jesus' whole body is embarrassing and shameful. Twisted. Consequently, the Corinth painting shakes our faith. Where is God in that scene? Where is God?

Although I appreciate the painting of Raphael I admire the Corinth painting for its ability to recover for us the utter scandal and God-forsakenness of the cross. It helps us understand why the Crucified God of the early Christians was so incomprehensible to its first cultural audience.

How could the cross, this ugly cross, be the foundation of this faith?

And why?