I have been arguing for a reevaluation of the concept known as Original Sin. Basically, I've argued that Original Sin is more extrinsic, situational, and circumstantial than intrinsic, dispositional, and innate. My arguments to this point have been inspired by the social sciences: Economics, psychology, sociology. In this post I want to support my argument with the biblical witness.

I have been arguing for a reevaluation of the concept known as Original Sin. Basically, I've argued that Original Sin is more extrinsic, situational, and circumstantial than intrinsic, dispositional, and innate. My arguments to this point have been inspired by the social sciences: Economics, psychology, sociology. In this post I want to support my argument with the biblical witness.

To do this I'm going to borrow the analysis of Tom Holland in his book Contours of Pauline Theology. Given that most of the texts used to support the doctrine of Original Sin come from Paul we should, obviously, take this issue right to the source.

The question I'd like to ask is simply this: Did Paul really teach the doctrine of Original Sin?

To start, note that Holland's work isn't about Original Sin, but his fresh reading of Paul does have implications for the doctrine. What I'd like to do in this post is summarize the parts of Holland's work that I think have implications for the doctrine of Original Sin.

The main thrust of Holland's reading of Paul is to suggest that Paul was a New Exodus theologian. The original Exodus involved God liberating his people from bondage, leading them through the waters and wilderness, back to the Promised Land. But after the fall of the Davidic dynasty and subsequent exile the Old Testament prophets, namely Isaiah, began to hope for a New Exodus. Critical features of this New Exodus would mirror the former Exodus from Egypt. It would be led by a descendent of David who was anointed by the Holy Spirit (Isaiah 11.1-2). This descendent of David would lead God's people through the wilderness to a new Eden (Isaiah 51.3). A New Covenant would be established between God and his people (Isaiah 9.6-7). Hearts would be circumcised (Jeremiah 31.31-34). A New Temple would be built (Ezekiel 44-45) where all the nations will gather to worship (Isaiah 2.1-5). And God will be married to his people and a great banquet will be thrown in celebration (Isaiah 54.1-8). (Contours, pp. 20-21)

It is Holland's argument that the New Exodus imagery of the Old Testament prophets framed the way the early church saw the Christ Event. There are many overt New Exodus passages in the New Testament (e.g., Acts 26.17-18; Galatians 1.3; Colossians 1.12-13; Revelation 1.5-6; Luke 1-2) but Holland goes further to suggest that the New Exodus imagery is the central motif of the New Testament, particularly the writings of Paul.

Holland argues that Paul, as a New Exodus theologian, builds his soteriology upon the paradigmatic salvation event in Jewish history: The Exodus, with a particular focus on the Passover. Thus, all of the categories that we find in Paul--sin, faith, justification, atonement, baptism, law, grace--should be read in light of the Exodus. Since most modern readers of Paul have failed to do this (particularly the Reformers) we've tended to get skewed readings of Paul. Holland concludes his book with these words:

"The conclusion of this study is that two major lenses have been missing from virtually all New Testament exegesis and that their absence has had a detrimental effect on properly appreciating the message of Paul. The first is the lens of the Passover and the second is the lens of a corporate reading of texts." (Contours, p. 291)

Unpacking this quote, Holland's argument is that by neglecting the Passover imagery Reformed theologians built their views of atonement and justification around legal metaphors. That is, the metaphor of salvation became about crime and punishment rather than rescue and deliverance. The second problem was that the Reformers read the passages concerning sin, faith, justification and baptism as dealing with individuals. You were a sinner who, as an individual before God, had to receive the gift of grace. But the Exodus was a corporate, collective event. A people were delivered from slavery. True, nations contain individuals, but the salvation experienced in the Exodus was a collective event.

If we follow Holland and read Paul through New Exodus lenses then suddenly Paul reads quite differently.

Here is one implication of this reading. According to Paul, "salvation" isn't about dealing with personal sin or guilt. It is, rather, God lifting a group of people out of bondage and creating a New Covenant with them (often symbolized as a marriage). As Holland writes:

"Paul sees that behind the conflict and alienation that man experiences is a whole universal order of rebellion. Man is at the centre of this struggle as a result of being made in God's image. Satan, the one who has sought the establishment of a different kingdom from that which God rules, has taken man, and all that he was made responsible for through creation, into bondage in the kingdom of darkness. The redemption of Christ is about the deliverance of man and 'nature' from this alienation and death." (Contours, p. 110)

All well and good, but it is critical to insist that this deliverance from bondage didn't happen in the privacy of our own hearts and prayers. Like the Exodus, the New Exodus is a corporate and historical event:

"The concept is not individualistic, as it is so often held, but is corporate, speaking of the state of unredeemed humanity in its relationship to Satan (Sin)." (Contours, p. 108)

"Thus, in Christ's death, there is not only a dealing with the guilt of sin and its consequences, but also the severing of the relationship with sin, in which unregenerate mankind is involved. It is an experience that encompasses the individual, but it is much more than solitary salvation. It is the deliverance of the community by the covenantal annulling effect of death...Having been delivered from membership of 'the body of Sin', the church has been brought into union with a new head and made to be members of a new body, 'the body of Christ'. (Contours, p. 110)

How might this new reading affect Pauline texts that seem to support the notion of Original Sin? Well, to take the case noted in the quote above, we can consider Paul's use of the phrase "the body of sin."

When Paul speaks of "the body of Sin" it sure seems like he's teaching Original Sin. But Holland argues that this conclusion only comes about if we read the phrase "the body" individualistically. That is, we are tempted to think that Paul is referring to your body and my body. But Holland argues that "body of Sin" is best read corporately. That is, we are a part of a larger body, a group of people, who are captive to sin. Paul's teaching here isn't that your particular human body is inherently sinful. No, "body of Sin" is a term of membership, designating which group you belong to. To quote Holland:

"...Paul sees the relationship between Satan and the members of his community, the body of Sin, as a parallel to that existing between Christ and his people. This ought not to be too difficult to accept in that the New Testament is constantly making comparisons between the members of these two communities that show corresponding relationships. Believers are citizens of the kingdom of light, unbelievers of the kingdom of darkness. Believers are the children of God, unbelievers are the children of the devil. Believers are the servants of God, unbelievers are the servants of the devil. These parallels ought to suggest that Paul would not find any difficulty in taking these comparisons to their ultimate conclusion. Believers are members of the body of Christ, unbelievers are members of the body of Sin." (Contours, p. 100)

If sin is about membership with a group rather than about some innate taint, then our reading of Paul completely overturns the notion that Paul taught anything like the doctrine of Original Sin. Holland is clear on this point (Contours, p. 110):

"It follows that the body is not in some way the bearer of sin nor is sin a deformation that is biologically inherited as some have suggested...[Sin] is relational rather than legal...Whether a man or a woman is righteous or a sinner in the biblical pattern of thinking depends upon the community to which they belong."

"Appreciating that the body is not the seat of sin as the traditional interpretation of the 'body of sin' suggests, allows us to realize that our humanity is God-given, even in its fallen condition. There ought not to be any shame in being human, nor in what such a reality implies. It should help us recognize that there are many natural emotions and desires that in themselves are not sinful and need no repentance; it is only their misuse that requires such a response."

In short, Paul didn't teach Original Sin at all.

Okay, then, how does this reading of Paul square with my Malthusian view of sin? Holland notes that in the New Exodus thinking the concepts of Death, Sin, and Satan get conflated. Paul often links sin and death (Romans 7.2-3; 8.1) in describing the satanic powers that enslave us. In other places sin and death are considered to be the Last Enemy to be defeated (1 Corinthians 15.45-55). These all appear to be echos that go back to the Exodus where the Angel of Death "passed over" the nation of Israel. As seen in the quotes above, Holland tends to lead with "Sin" and "Satan" but I think it is just as acceptable to lead with Death as the controlling power. Interestingly, this focus on death is supported by Holland's New Exodus reading. Specifically, consider Isaiah 28.16:

So this is what the Sovereign LORD says:

"See, I lay a stone in Zion,

a tested stone,

a precious cornerstone for a sure foundation;

the one who trusts will never be dismayed.

In the New Testament this "cornerstone" passage is the most frequently cited Old Testament passage to describe the New Covenant in Christ. But in the verses preceding this passage (verses 12-15) a description is given of the Old Covenant from which the New Exodus will provide rescue (emphases added):

...to whom he said,

"This is the resting place, let the weary rest";

and, "This is the place of repose"—

but they would not listen.

So then, the word of the LORD to them will become:

Do and do, do and do,

rule on rule, rule on rule;

a little here, a little there—

so that they will go and fall backward,

be injured and snared and captured.

Therefore hear the word of the LORD, you scoffers

who rule this people in Jerusalem.

You boast, "We have entered into a covenant with death,

with the grave we have made an agreement.

When an overwhelming scourge sweeps by,

it cannot touch us,

for we have made a lie our refuge

and falsehood our hiding place."

I don't think a better description of our Malthusian plight could found than "We have entered into a covenant with death, with the grave we have made an agreement." And, interestingly, this Malthusian-inspired "pact with death" is the New Exodus description of what we call "Sin" or "Satan" in the New Testament.

In sum, I think Holland's New Exodus framework can be easily adopted to fit the model I'm building around a Malthusian notion of sin. Specifically, the "law of sin and death" is the how the Malthusian forces enslave the human mind. Death here, as I've argued, is read very literally. The specter of death drives human sinfulness. Again, we are not inherently evil. But we are in bondage, members of the body of Sin. And our bondage is biological rather than spiritual. (Or, rather, the biological infects and pushes around the spiritual.) That is, our biology tethers us to a survival instinct that is enslaved to Malthusian forces. If we submit to those Malthusian pressures, to the law of sin and death, then we are in Sin. We are submitting, as servants, to the Power of this World. You can call that power Satan if you like.

Salvation, as Holland has shown us, is being set free from the bondage of Sin. Again, saved not in a private, individualized way where the sin "inside" me is removed. Rather, salvation depends, to use Holland's words, "upon the community to which you belong." If you are a member of the Malthusian world you play/live by those rules, the rules of sin and death. The Malthusian rules of survival of the fittest. But Christ has created a New Community, the body of Christ, the church, that has been set free from the "law of sin and death." Those in the body of Christ do not live according to the self-interested impulses forced upon them by the Malthusian world. Death can't push around the body of Christ. Freed from the Angel of Death, who passes over due to the blood of the Lamb, the body of Christ can live sacrificially and lovingly. A feat impossible when in bondage to Satan. Or Sin. Or Death. Or Malthus. Or whatever you want to call it.

Next Post: Part 5

Original Sin: Part 3, Immoral Society in a Malthusian World

In my last post I made the case that human acquisitiveness isn't driven by an innate and sinful selfishness. Rather, human acquisitiveness is a logical and predictable adaptation to living in a Malthusian world. In this post I want to move away from individuals and consider human society in a Malthusian world.

In my last post I made the case that human acquisitiveness isn't driven by an innate and sinful selfishness. Rather, human acquisitiveness is a logical and predictable adaptation to living in a Malthusian world. In this post I want to move away from individuals and consider human society in a Malthusian world.

To make my point I'm going to borrow the sociological and anthropological analysis offered by Reinhold Niebuhr in his classic book Moral Man and Immoral Society.

First, we should acknowledge that the reactions to Niebuhr's "political realism," as articulated in Moral Man and Immoral Society, have been diverse, contradictory, and controversial. Most of the controversial bits in Moral Man and Immoral Society come in the second half of the book. What I'd like to do is focus on the first half of Moral Man and Immoral Society, the sociological analysis.

In the first half of Moral Man and Immoral Society Niebuhr makes the argument that informs his title. That is, individual persons have a chance at behaving morally while societies, inherently, cannot. As Niebuhr writes:

Individual men may be moral in the sense that they are able to consider interests other than their own in determining problems of conduct, and are capable, on occasion, of preferring the advantages of others to their own. They are endowed by nature with a measure of sympathy and consideration for their kind, the breath of which may be extended by an astute social pedagogy...But all these achievements are more difficult, in not impossible, for human societies and social groups.

Why are these moral achievements impossible for social groups? To provide his answer Niebuhr describes the psychological prerequisites necessary for moral behavior. These are empathy and perspective. Humans, as individual moral agents, can, at various times and places, pull these moral levers. They can experience compassion and envision life from the other person's perspective. By contrast, Niebuhr argues that social groups are too large and heterogeneous to get everyone's sympathies and viewpoints in line. As Niebuhr writes:

[Nations] know the problems of other people only indirectly and at second hand. Since both sympathy and justice depend to a large degree upon the perception of need, which makes sympathy flow, and upon the understanding of competing interests, which must be resolved, it is obvious that human communities have greater difficulty than individuals in achieving ethical relationship. While rapid means of communication have increased the breath of knowledge about world affairs among citizens of various nations, and the general advance of education has ostensibly promoted the capacity to think rationally and justly upon the inevitable conflicts of interests between nations, there is nevertheless little hope of arriving at a perceptible increase of international morality through the growth of intelligence and the perfection of means of communication.

In short, social groups are moral idiots, in the the old meaning of the term: Lacking skill. Morality involves accurate information to weigh various goods, fellow-feeling, and the ability for self-transencence. Although individuals can, and often do, accomplish these things it is impossible to get a whole group of people to behave, collectively and spontaneously, in a moral manner.

This doesn't make social groups inherently evil. It does, rather, suggest that social groups tend to be rather deaf and sluggish when it comes to doing "the right thing." Take, for example, America's response to Rwanda or Darfur.

But here is Niebuhr's point: This isn't going to change. It's impossible to change it. As Niebuhr notes, better education and a flatter world may improve the moral capabilities of social groups and nations but any improvement will be modest. Someone, somewhere is just not going to be on the same page. They will have been affected by skewed information or are just plain out of the loop. Darfur? Where is Darfur? By the time you get the national conscience informed and sensitized it is often too late.

My point isn't that nations can't be evil. It is, rather, that nations can't be good. And this moral idiocy isn't due to Original Sin. It's simply a sociological dynamic.

Just to be clear, this isn't to say that any of this is okay. It's horrible the way nations behave. It's abominable how slow nations react to world catastrophes and needs. Thus, we should do everything we can to spread the word, rouse the passions, and rally our fellows. But even if much of what we are fighting against is demonic or the product primal human depravity I'm suggesting that, even if you subtract those things out, societies will still be immoral due to the fact that social aggregates, per Niebuhr's analysis, cannot move cohesively and nimbly in the face of moral challenges.

In short, you don't need to posit human depravity to get a pretty crappy world. The world is going to be fundamentally immoral because groups are, through no intrinsic fault of their own, moral idiots. And this brings me back to my Malthusian theme that we are finite creatures in a finite world. We don't need to go into the souls of men to look for a twisted worm at the core. We might, rather, take note of extrinsic factors, like impersonal sociological dynamics, that make morality difficult if not impossible to achieve.

Next Post: Part 4

Original Sin: Part 2, Human Acquisitiveness in a Malthusian World

How do we account for greed in a Malthusian world?

How do we account for greed in a Malthusian world?

In my last post I argued that the root cause of human sinfulness is living as biodegradable creatures in a world of potential scarcity. This situation makes the human species feel vulnerable and anxious.

But how can this model explain human acquisitiveness in times of plenty? Why is corporate greed rampant in capitalistic economies? Where does greed come from if we are well off? How can Malthus explain American consumerism? Don't we have to posit some kind of intrinsic selfishness to explain all this?

No doubt we are selfish. But again, I'd like to argue that the selfishness gets into us from the outside, from the Malthusian context.

Why are we so acquisitive? An Augustinian treatment would claim that it is due to some intrinsic defect, Original Sin. I've argued that a better place to look for an answer is in the Malthusian predicament humans find themselves in. In short, is human acquisitiveness best explained by an appeal to intrinsic human "selfishness" or by examining how acquisitiveness might be a perfectly logical response to surviving in a Malthusian world?

So, let's ask one more time: Why are humans so acquisitive? The answer, obviously, is that humans discount the future hyperbolically.

You probably want me to unpack that.

To start, it is a fact that we discount the future. As they say, a bird in the hand is better than two in the bush. An immediate reward is more valuable than a delayed reward, even if that delayed reward has a higher value. For example, let's say I offer you a choice:

Choice A: $100

Choice B: $200

Which would you choose? Well, any idiot can make that choice. Okay, then, how about this choice:

Choice A: $100 right now

Choice B: $200 a year from today

Most people take the $100 right now. Why? They discount the future. Although $200 is, in absolute value, more than $100 it is not as valuable in relative terms because it is one year in the future. The $200 has been discounted and is now perceived as less valuable than the $100.

How much less? Well, that is an important psychological question. The issue of human acquisitiveness rests upon how steeply humans discount the future. Let me try to illustrate this. Choice A is $100 right now. Next, I'll offer a variety of choices for Choice B, each at a different time horizon. Look through the list and decide when you'd move from Choice A ($100 right now) to one of the following:

Choice B:

a) $200 a year from today

b) $200 six months from today

c) $200 three months from today

d) $200 one month from today

e) $200 two weeks from today

f) $200 one week from today

g) $200 three days from today

h) $200 one day from today

i) $200 12 hours from now

h) $200 one hour from now

i) $200 30 minutes from now

j) $200 one minute from now

h) $200 right now

At what point, (a) through (h), do you pick Choice B?

As we noted, at time offerings around (a)-(c) people would rather just take the $100 than wait so long for $200. They discount the future. Conversely, when we look at time offerings around (i)-(j) it seems pretty easy to wait a bit for the $200. That is, as the time horizon for the offer approaches the present the discounting is less and less. We see the $200 as $200 and, thus, prefer it to $100.

In short, time and value are inversely related: Immediate payoffs are more valuable than distant ones. As the offer moves away from us in time we increasingly discount it. As it approaches us in time the discount decreases.

The question for psychologists is what does this discount curve look like? How much do people discount the future? What we are looking for is the shape of what is known as the "discounting curve."

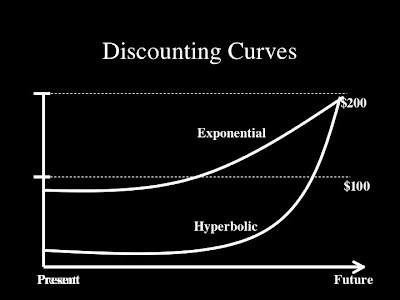

Simplifying greatly, the discounting curve can take one of two shapes. It can be either exponential or hyperbolic in shape. The difference between the exponential and hyperbolic discounting curves is simply this:

If people start moving to Choice B early in the example above--in the (a)-(d) range--then they are discounting the future, but not very much. The discounting curve is shallow (i.e., exponential).

If people start moving to Choice B very late in the example above--in the (e)-(h) range--then they dramatically discount the future. The discounting curve is steep (i.e., hyperbolic).

If you want a graphical representation of what is going on, I made this slide to illustrate the two curves:

Value is on the horizontal axis and Time is on the vertical axis. The graph shows the value of $100 right now (Present) and $200 offered some time in the future. The graph shows that the future is discounted: The curves representing the value of the $200 are both below (i.e., less valued) the $100 being offered right now. The interest of the graph is in how the curves behave as we move through time, left to right. If you put your finger on the exponential curve starting at the left and moving to the right you notice that very quickly your figure goes above the $100 line. That is, the exponential line discounts the future but not by much. The "true value" of the $200 is quickly experienced and preferred. By contrast, if you trace the hyperbolic curve you remain under the $100 line longer. We are steeply discounting the future on this curve. The $200 offer only takes on its true value when the offer is immediately at hand.

Graphs aside, the sum of the matter is this: If people are exponential discounters then we can wait. If we are hyperbolic discounters then we can't wait.

What does all this have to do with human acquisitiveness? Well, the scientific consensus, from scores of studies on this topic, is that humans discount the future hyperbolically. We prefer a bird in the hand to two in the bush. Smaller and immediate rewards are seen as more valuable than larger more distant rewards.

It is the hyperbolic discounting curve that sits behind what the Greeks called akrasia, or "weakness of will." Specifically, we find it difficult to reach our long-term goals because we discount the future so steeply. We give in to short-term temptations, even when we know that the short-term payoff is less valuable than the long-term goal. It's all driven by the hyperbolic discounting.

Why, it might be asked, are we so weak-willed? Why do we discount hyperbolically? The answer brings us back to Malthus. In a time of plenty our hyperbolic discounting psychology is maladapted. We eat too much, spend too much, consume too much. It is hard to save, hard to wait. But evolutionary psychologists have argued that a hyperbolic discounting curve would have been ideally suited to life during human pre-history. That was an age characterized by food scarcity, famine, and a lack of food preservation technology. In those stone age cultures if a large food source was found (e.g., a mammoth kill, berries in season) then gorging yourself has a kind of adaptive logic. Tomorrow, the food will be either gone or spoilt. In that world, a bird in the hand is truly better than two in the bush. Consume the resources now while you have the chance. Who knows what tomorrow might bring?

The point is, all this human acquisitiveness--the gluttony, the akrasia, the consumerism--isn't due to an intrinsic Augustinian defect. It is, rather, an adaptation that humans acquired through eons of struggling in the Malthusian situation. And with this understanding of the psychological machinery we can now explain a wide variety of phenomena from failing to stay on a diet to credit card debt to corporate greed.

It's all the logical outcome of hyperbolic discounting, a trait ideally suited to existence in a Malthusian world.

Next Post: Part 3

"Can you get to heaven from the potty?"

"Can you get to heaven from the potty?"

"Can you get to heaven from the potty?"

--Quote from my son Aidan after we flushed a dead pet fish down the toilet.

Last night my wife reminded me of the question Aidan asked a few years back. As I pondered the question I thought to myself, "You know, that question just summarized my last post in eight words." Not bad, not bad at all.

Given the profundity of the question "Can you get to heaven from the potty?", and in response to some of your comments, I'm going to be saying with the Malthusian theme for at least three more posts and have now designated the last post as a "Part 1".

Hopefully, by the end, we'll have an answer to Aidan question.

Original Sin: Part 1, Human Biodegradability in a Malthusian World

I have always struggled with Augustinian and Calvinistic notions of Original Sin. These formulations tend to posit some sort of intrinsic defect within the human creature, a stain as it were. As a psychologist I spend a great deal of time thinking about human motivation and have gone on long searches for the psychological fingerprints of Original Sin. If humans are totally depraved then there should be some motivational or cognitive bias, some tilt of the mind, that produces the depravity.

I have always struggled with Augustinian and Calvinistic notions of Original Sin. These formulations tend to posit some sort of intrinsic defect within the human creature, a stain as it were. As a psychologist I spend a great deal of time thinking about human motivation and have gone on long searches for the psychological fingerprints of Original Sin. If humans are totally depraved then there should be some motivational or cognitive bias, some tilt of the mind, that produces the depravity.

What is the psychological source of sin? What, exactly, is wrong with us?

Generally, we tend to think of human self-interest, selfishness, as the root cause of human sin. In the language of Augustine we are "curved in on ourselves" (incurvatus in se). This self-focus contaminates even our best moral efforts. As Martin Luther said, "Every good work is a sin."

However, I've come to the conclusion that this self-focus isn't an intrinsic defect as is typically posited by Original Sin theories. More and more, I think Original Sin is an extrinsic force, it is situational rather than dispositional.

Basically, we are finite creatures living in a finite world. In short, our situation is Malthusian. You'll recall that Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) was the English clergyman who wrote one of the fundamental essays of economics. It was entitled An Essay on the Principle of Population. In the Essay Malthus made the observation that reproduction tends to outstrip (or will eventually outstrip) resources. When this happens organisms must fight over the diminishing resources in order to survive (this was the key insight that triggered Darwin's thinking when he read the Essay). Taking the long view, Malthus applied this analysis to future human history and predicted that, given the logic of mathematics, population growth would soon outstrip food supply leading to catastrophic human death. From the Essay:

"The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race. The vices of mankind are active and able ministers of depopulation. They are the precursors in the great army of destruction, and often finish the dreadful work themselves. But should they fail in this war of extermination, sickly seasons, epidemics, pestilence, and plague advance in terrific array, and sweep off their thousands and tens of thousands. Should success be still incomplete, gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the world."

Now, you might have noticed, the Malthusian catastrophe has yet to come to pass. Malthus was working with an agrarian model of economics, limiting his ability to foresee how division of labor (among other things) could create wealth (i.e., the pin factory from Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations). To illustrate how we've been able escape Malthus's predictions, consider the recent analysis given in Gregory Clark's book A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World. As documented by Clark (and others), most of human history has been governed by Malthusian dynamics where birth and death rates, along with available food supplies, set strict limits upon human population. But with the onset of the Industrial revolution wealth began to be created at a rapid clip. And with it a population explosion. This rapid increase in wealth is strikingly illustrated by this chart of Clark's (p. 2):

As can be seen in Clark's graph, since the onset of the Industrial Revolution much of the world has been able to rocket out of the Malthusian trap. (How and why, and why some countries are still stuck in the trap, is the subject of Farewell to Alms.)

So it seems that we can shrug Malthus off. We've escaped his grim prediction.

But have we?

Despite the wealth-creating ability of modern economies, the ability that lifts us out of Malthusian economics, the Malthusian specter is always lingering in the background. It functions, as it were, as a center of gravity. Modern economies are like airplanes. They are high-powered machines that can lift us off the earth and get us into the clouds of prosperity. But as we all know, airplanes crash. And when they do we are back in the Malthusian situation. Only this time with billions of more mouths to feed.

People frequently speculate about these apocalyptic Malthusian crashes. Sometimes it appears in crazes like the Y2K hysteria. Remember how the global economy was going to crash when January 1, 2000 rolled in? How all the world computers and machines or appliances with computer chips would stop functioning? Planes falling out of the sky? Etc.?

But there are respectable Malthusian analyses regarding things such peak oil, the population explosion, and environmental collapse. Some of these are analyses are alarmist, but many are done soberly and with quantitative care. The point is always the same: We are finite creatures in a finite world. And we can't escape that fact.

I've gone into Malthus because my view of sin is largely informed by his Essay. I tend to reject theological notions that sin is a product of an intrinsic human defect. I tend to see sin as extrinsically caused. The problem isn't on the inside, it is, rather, on the outside. And the outside, at root, is governed by Malthusian dynamics. Modern economies tend to hide that fact from us, but Malthus' Essay is still in force.

We are, in short, vulnerable. And in times of economic downturn or times of war or during times of natural disaster when our electric grids and food supply lines get broken we face, again, the ghost of Malthus. He's always there.

We are selfish not because of a "fallen" nature. We are selfish because we live as physically vulnerable creatures in a Malthusian world. It is this situation that tilts the mind toward selfishness, makes us competitive, makes us hoard, or preemptively attack. It is our felt vulnerability that makes us sinful.

This vulnerability is nicely described by Marilyn McCord Adams in her book Christ and Horrors (p. 38):

"There is a metaphysical mismatch within human nature: tying psyche to biology and personality to a developmental life cycle exposes human personhood to dangers to which angels (as naturally incorruptible pure spirits) are immune...[this] makes our meaning-making capacities easy to twist, even ready to break, when inept caretakers and hostile surroundings force us to cope with problems off the syllabus and out of pedagogical order. Likewise, biology--by building both an instinct for life and the seeds of death into animal nature--makes human persons naturally biodegradable. Human psyche is so connected to biology that biochemistry can skew our mental states (as in schizophrenia and clinical depression) and cause mind-degenerating and personality-distorting diseases (such as Alzheimer's and some forms of Parkinson's), which make a mockery of Aristotelian ideals of building character and dying in a virtuous old age."

The Bible often links the powers of sin and death. Generally, we tend to spiritualize the connection between the two. I'd like to read the connection more concretely, economically, and biologically. Death and sin are linked by Malthus. The specter of death is what creates the sinful behavior. This is, interestingly, the view of sin and death in the Orthodox tradition. As the theologian S. Mark Heim describes the Eastern view:

Removed from Eden we are "[u]nourished by the divine energy, our existence fades into subjection to corruption and death. In such a state, our mortality becomes a source of anxiety. Futile attempts to defend ourselves from it lead us into active sin and estrange us from trust in God. Now sinfulness is more a result of mortality than mortality from sinfulness. To say that humans are 'conceived in sin' does not mean that some guilt or evil inclination is passed on to them in the act of their conception, but that what they inherit is a mortal human nature, which became mortal as a result of sin."

After the Fall, it is death that makes us paranoid and self-interested. But this is not, simply, some generalized or diffuse fear of death. It is a Malthusian fear, a fear that seeps into you because you are a biodegradable creature living in a Malthusian world.

Next Post: Part 2

Adverbial Placement & the Oath: Things I'm Interested In (Installment #7)

Being the huge nerd I am, I really enjoyed this analysis. And, of course, I'm sure you all know that President Obama and Chief Justice Robert did a "do over" today.

Being the huge nerd I am, I really enjoyed this analysis. And, of course, I'm sure you all know that President Obama and Chief Justice Robert did a "do over" today.

The major flub occurred with the adverb "faithfully." The line should read:

"...that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States."

As Zimmer points out in his analysis (And who knew so much about abverbial placement until today?), the adverb can be placed in one of three places to keep the sentence semantically coherent:

"...that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States."

"...that I will execute faithfully the office of President of the United States."

"...that I will execute the office of President of the United States faithfully."

The Constitution specifies the first wording. Roberts, apparently nervous and tripped up a bit when Obama jumped in early, noticed he had missed his chance to get "faithfully" before or directly after the word "execute." So, he did the next best thing and added it at the end of the sentence. Obama seemed to notice the change of wording and hesitated. From there they just muddled through.

Good times for English teachers all around.

The Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television: Profanity as Gnostic Affront

"The whole problem with this idea of obscenity and indecency, and all of these things--bad language and whatever--it's all caused by one basic thing, and that is: religious superstition…that the human body is somehow evil and bad and there are parts of it that are especially evil and bad, and we should be ashamed. Fear, guilt and shame are built into the attitude toward sex and the body."

--George Carlin (Interview with Associated Press, 2004)

The Puzzle of Profanity

There is little scientific consensus as to why profanities tend to cluster around specific themes. For example, in popular culture the paradigmatic inventory of profanity is George Carlin’s famous list of “The Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television.” Commenting on Carlin’s list, the psychologist Steven Pinker (2007, p. 326-327) has noted the following:

The seven words you can never say on television refer to sexuality and excretion: they are names for feces, urine, intercourse, the vagina, breasts, a person who engages in fellatio, and a person who acts out an Oedipal desire.But it’s not only sexuality and excretion that are implicated in profanity. Pinker goes on:

But the capital crime in the Ten Commandments comes from a different subject, theology, and the taboo words in many languages refer to perdition, deities, messiahs, and their associated relics and body parts. Another semantic field that spawns taboo words across the world’s languages is death and disease, and still another is disfavored classes of people such as infidels, enemies, and subordinate ethnic groups. But what could these concepts—from mammaries to messiahs to maladies to minorities—possibly have in common?(An online version of Pinker's book chapter can be found here.)

Pinker suggests that these semantic clusters can be united by noting that profanity generally creates a strong negative emotion. More specifically, many profanities appear to be associated with the psychology of disgust and contamination. Urine, feces, blood, and other bodily effluvia are routinely referenced in obscene speech as well as being reliable disgust elicitors. But the profanity/disgust link is incomplete as it fails to capture facets of religious cursing (e.g., damn, hell), references to sexual intercourse (e.g., the f-word), or references to body parts (e.g., breasts, genitalia). What can link these sources of profanity?

Profanity and Disgust: A Terror-Management View

Terror Management Theory (TMT) is fast becoming one of the most influential theoretical and empirical paradigms in social psychology. Rooted in existential psychology, primarily the work of Ernest Becker (1973), TMT attempts to understand the psychological mechanics involved in how persons cope with existential “terrors,” most notably the fear of death.

One facet of TMT research has been to examine how various facets of everyday existence can become existentially problematic, particularly when functioning as death reminders. We are unsettled upon being reminded of our death and, thus, tend to repress or avoid aspects of life that make death salient. Much of this research has focused on how the body functions as a mortality reminder. The vulnerability of our bodies highlights the existential predicament that we will one day die and decay. Further, the gritty physicality of the body (e.g., blood, sweat, odors, waste) highlights our animal nature which functions as an existential affront to our aspirations of being transcendent spiritual creatures. Based upon these insights, an impressive body of empirical work has strongly linked body ambivalence to death concerns. Much of this research is summarized by Goldenberg, Pyszcynski, Greenberg, & Solomon (2000) who conclude: “[T]he body is a problem because it makes evident our similarity to other animals; this similarity is a threat because it reminds us that we are eventually going to die.”

The TMT research mentioned above is consistent with a theory posited by Rozin, Haidt, and McCauley (2000) regarding the association between disgust and death. Specifically, beyond the aversions associated with oral incorporation (called “core disgust”), the following stimuli are known as reliable disgust elicitors: Body products (e.g., feces, vomit), animals (e.g., insects, rats), sexual behaviors (e.g., incest, homosexuality), contact with the dead or corpses, violations of the exterior envelope of the body (e.g., gore, deformity), poor hygiene, interpersonal contamination (e.g., contact with unsavory persons), and moral offenses. After separating out disgust associated with social contact or moral offenses (called “sociomoral disgust”), Rozin, Haidt, and McCauley have grouped the remaining disgust domains under the category “animal-reminder disgust.” Rozin et al. argue that the coherent theme of the “animal-reminder” domain is that each stimulus highlights the physical vulnerability of the human body which, in turn, functions as a death/mortality reminder.

The F-Word: Sex, Death, and the Body

Although it may seem obvious that corpses, gore, or physical deformity function as death reminders, it might be less clear as to why sexual intercourse, one of the most pleasurable of human experiences, is the referent for one of the strongest profanities—the f-word—in the English language. One theory, obvious when considered in conjunction with the anger with which the f-word is often used, is that references to sex function as forms of verbal sexual assault (e.g., see Neu’s, 2007, analysis of the f-word). But this theory is limited in explaining the use of the f-word in contexts where aggression isn’t implicated. For example, sexual partners might say “Let’s f***” in contrast to “Let’s make love”. Although the referent is the same in each sentence the connotation is very different, and not necessarily negatively so

Is it possible that the f-word functions as a death reminder? A recent study by Goldenburg, Pyszcynski, McCoy, Greenburg, and Solomon (1999) is very suggestive here. Specifically, in the Goldenburg et al. study participants high in neuroticism were separated into one of two imagery groups. One group was asked to imagine the spiritual/romantic aspects of sexual intercourse (e.g., being loved by the partner, connecting spiritually with the partner). In contrast, the second group was asked to imagine the physical/bodily aspects of the sexual encounter (e.g., tasting bodily fluids, skin rubbing). After the imagery exercise the two groups were asked to engage in a word-fragment completion task where the word-fragments (e.g., sk_ll, coff _ _) could be completed in either a death (e.g., skull, coffin) or non-death (e.g., skill, coffee) related manner. The results indicated that thinking about the physical/bodily aspects of sex created greater death thought accessibility (i.e., those in the physical imagery condition were significantly more likely to complete the words as skull or coffin than as skill or coffee).

Given this death/sex link, Goldenburg et al. suggest that sex is psychologically complicated for humans. On the one hand, as we have been discussing, sex can be a disgusting reminder of our bodily functions and dependencies. And yet, sex is also experienced as a spiritually transcendent act, where “two fleshes become one.” In short, the physical aspects of sex are latent mortality reminders while the relational and emotional aspects of sex transport the act into the spiritual and sacred realm of human experience.

It appears, then, that the f-word exploits the fissure that exists between the physical and the spiritual aspects of sex. Properly understood, sex is a dual act, a union of both the physical and the spiritual. Stripped of its spiritual significance and meaning, sex is reduced to its animal function. This is the f-word’s power. It strips sex of its spiritual significance, reducing the act to physical manipulations. It short, the f-word functions, literally, as a profanity. Something that is considered to be sacred is stripped of its spiritual content and rendered profane

(However, as noted above, this “profaning of sex” can be playful exploited by sexual partners who use the f-word. Saying “Let’s f***” in contrast to “Let’s make love” is a request for a sexual encounter that is more physical than sentimental. That is, consistent with the theory above, the f-word is picking out the body, as opposed to the spirit, as the locus of pleasure. But it should also be noted that, for the healthy couple, this request is playful in that it picks out the body against the backdrop and context of the deeper and more fundamental spiritual relationship.)

Profanity as Gnostic Affront

How does profanity relate to the psychology of religious belief? If profanity functions as a body/death reminder then attitudes about profanity may vary within and between Christian populations. Specifically, attitudes about profanity would depend upon how the body is psychologically and theologically experienced within a particular faith community.

Why would this be the case? As an answer we can note that, from the earliest days of the church, beginning with the Gnostic heresies, many Christian communities have struggled with the body as a locus of theological reflection. As Philip Lee (1987, p. 49) has noted in his historical survey of Gnostic influences upon Christianity, “From Simeon Stylites to St. Francis of Assisi to certain aspects of Calvinism, the aversion to this world with a desire to escape it has been one of the most prominent strands in the fabric of Christianity.” Furthermore, this aversion has “led to some unfortunate attitudes toward the flesh, human nature, and sexuality” within contemporary Christianity. This suspicion of the body has deep roots in American evangelicalism. Take, for example, this assessment of Jonathan Edwards, a leader of early American Protestantism:

The insides of the body of man is full of filthiness, contains his bowels that are full of dung, which represents the corruption and filthiness that the heart of man is naturally full of.A similar sentiment comes from the Puritan leader Cotton Mather. Mather’s lament about the depravity of the body is triggered by his encounter with a dog while urinating:

I was once emptying the Cistern of Nature, and making Water at the Wall. At the same Time, there came a Dog, who did so too, before me. Thought I; “What mean and vile Things are the Children of Men, in this mortal State! How much do our natural Necessities abase us and place us in some regard, on the Level with the very Dogs!”…Accordingly, I resolved, that it should be my ordinary Practice, whenever I step to answer the one or other Necessity of Nature, to make it an Opportunity of shaping in my Mind some noble, divine Thought.Mather’s reflection is a near perfect illustration of the animal-reminder facet of disgust. Mather finds urination, one of many “natural Necessities,” to be dog-like and, as such, an affront to human dignity. In addition, throughout Christian history the church has expressed ambivalence concerning human sexuality. Celibacy, complete non-participation in sex, has throughout church history been expressed as a spiritual ideal.

Given Gnostic sensibilities concerning the body, sensibilities still evident in many sectors of Christianity, it seems reasonable to posit that profanity may function as a kind of Gnostic affront to certain Christian believers. Specifically, if a rejection/suspicion of the body (a Gnostic stance) is rooted in death anxiety then profanity, as an animal/body reminder, would be particularly offensive to these believers. By contrast, Christians less suspicious and more welcoming of the body (contra Gnosticism) would be predicted to be less reactive to profanity, less offended or bothered by it.

Summary

From a definitional standpoint, profanity and vulgarity share semantic core. Specifically, something is profaned when its sacred or holy character is defiled and debased rendering it “common.” In a similar way, vulgarity refers to “crude language.” But we should be quick to note that the origin of the word vulgar is rooted in the attempts of social elites to distinguishing their speech and habits from the lower, poorer classes. As with profanity, vulgarity is speech that takes something that is lofty and civilized and renders it as debased and common. Profanity and vulgarity are “gutter,” “bathroom,” or “barnyard” speech. It is “low” speech. And given the common metaphorical maps of High = Good and Low = Bad (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980), vulgar and profane speech is understood to be immoral, sinful, improper, filthy, and dirty.

The guiding theory of this research was that the physical body becomes implicated in the high/low good/bad mapping of profanity and vulgarity. As observed in the “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” profanity appears to semantically cluster around the body (e.g., body parts, sexual behaviors, body effluvia). If so, why are these body references considered to be “unclean,” “dirty” or “sinful”? This association (the body = offensive and sinful) has puzzled students of taboo language. One possible answer to this puzzle comes from the literatures of Terror Management Theory and disgust psychology. Summarizing, there is good empirical evidence that body references are disgusting and offensive because they function as death/mortality reminders. Consequently, as a verbal reminder of death, profanity functions as a psychological assault.

But where does religious belief and theology fit into this analysis? As we have observed, profanity and vulgarity presume a background assumption that something holy, spiritual, or elevated is being debased, brought “low,” and contaminated. A simple death reminder does not entail this contamination of the spiritual by the physical. What is necessary for this notion is a theological background where human existence is divided into the spiritual and the physical. Further, there must be an assumption, most salient in the Gnostic and neo-Platonic influences within Christianity, that the spiritual realm is holy and pure and that the body is dirty and a locus of contamination. With these backdrop assumptions in place it becomes clear how profanity acts as a Gnostic affront. By making salient the oozy and disgusting aspects of our bodies, profanity highlights our animal nature mocking any Gnostic pretensions that humans might escape, avoid, or minimize their physical existence. Profanity is a shock to a creature aspiring to be like the angels.

Note:

The study goes on to present some empirical research I just completed that supports the theory presented above. Also, my Feeling Queasy about the Incarnation study that was the antecedent for the profanity research has just appeared in press. You can find it here:

Beck, R. (2009). Feeling Queasy about the Incarnation: Terror Management Theory, death, and the body of Jesus. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 36, 303-312.

The Non-Verbals of Welcome: Part 3, A Daily Eye Muscle Workout

First, a test. Surf to the Spotting Fake Smiles Test and see how you do. The important piece is to note at the end of the test the main sign of fake vs. real smiles.

First, a test. Surf to the Spotting Fake Smiles Test and see how you do. The important piece is to note at the end of the test the main sign of fake vs. real smiles.

(I'll wait here until you finish the test.)

Okay, having finished the test you've seen a few fake smiles and a few real smiles and if you paid attention you picked up on the key contrast. Specifically, fake smiles only engage the lower half of the face. The risorius muscle of the face pulls the angle of the mouth upward. This produces more of a grin than a smile.

An authentic smile engages both the upper and lower face, basically the whole face changes. This is particularly noticeable around the eyes. In a real smile the orbicularis oculi muscle around the eye engages to create what is known as the "crow's feet" wrinkle around the eyes. Move this muscle a lot in a lifetime and the crow's feet become the permanent "laugh line" wrinkles around he eyes.

Importantly, parts of the movement of orbicularis oculi muscle are involuntary. This means that it takes some care and effort to intentionally give a full face smile. When asked to smile the most people can muster is a lower face grin. This is why children's school pictures tend to be so bad. The child is simply grinning, not smiling, and, as a consequence, their face doesn't reflect the happiness we see when we snap a candid photo of the child truly in the grip of joy. Getting a child to say "Cheese!" won't produce a smile, only a grin. This is why during photo shoots the photographer tries to do something funny to get the child to laugh. If something truly tickles a child's funny bone, the orbicularis oculi engages, involuntarily, transforming the eyes of the child. If you can snap the photo at that moment you've got gold.

Technically, the full-face authentic smile is called the Duchenne smile. It was so named after Guillaume Duchenne (1806-1875) who discovered the role of the orbicularis oculi muscle in full-face smiles. Interestingly, research has shown that the more Duchenne smiles you give the longer you live and the better your life will be. In a variety of studies researchers have examined the smiles in old photo almanacs (think of old high school yearbooks or church bulletins) coding the smiles as either grins or Duchenne. The researchers then locate these people, years after the photos were taken. How have these smilers fared since the time of that photo? Amazingly, a variety of studies have shown that those who gave Duchenne smiles (rather than grins) are healthier and happier and have lived longer than their counterparts.

But my interest here is less about what smiles can do for us than about what they can do for others. I've been focusing of the non-verbals of welcome. Given what we now know about smiles I want to make a comment about welcoming people with your facial expressions, specifically you smile.

In short, grins are easy. You can flash them at will. But they are perfunctory, cool, and generally unfriendly and unwelcoming. We think we are being nice when flashing a grin, and we are, but we all know they are fake. A forced social nicity.

Given all this I pay tons of attention to my face, intentionally noting when I'm simply grinning at people (seriously, I do this). When I'm in face to face interactions I try to pay attention to my eye muscles. This might sound crazy, but if you do this, you can, eventually, gain some control over the orbicularis oculi muscle and offer warmer, more full-faced smiles.

Now a cynic might counter, isn't this a bit of duplicity on your part? You are working hard at giving a "real" smile but, at root, you are working at it. The smile isn't spontaneous, even if it looks that way.

By way of response I would note that research also tells us that if you make a Duchenne smile your mood is affected. Literally, the more you smile the better you feel (recall the research about smiles and well-being). Further, we also know that we mimic facial expressions. If I smile at you, you'll, involuntarily, smile back. (This is due to what are called mirror neurons in the brain.) And when you begin smiling your mood is also affected for the good. In short, by offering a Duchenne smile I'm not trying to trick the person. I'm trying to set into motion a whole social/physiological system that promotes feelings of friendship, warmth, and welcome in both partners. You do this enough and people will notice a difference about you. They will seek you out, enjoy your company, and want to spend time with you. In short, people feel welcomed by you. And if you simply grin at people none of this happens.

So if you want to be a person of welcome my advice is this: Pay attention to the orbicularis oculi. Plus, the research says that a side benefit is a longer, more happy life.

Not bad for a daily eye muscle workout. Not bad at all.

Citizen's Briefing Book: Things I'm Interested In (Installment #6)

As a blogger I like this idea.

As a blogger I like this idea.

Click here to navigate to the Citizen's Briefing Book. Share your ideas, vote on ideas, and then see if they end up on the desk of the Oval Office.

The Non-Verbals of Welcome: Part 2, Holy Kisses, Handshakes, and Hugs

"Greet each other with a holy kiss."

"Greet each other with a holy kiss."

Romans 16.16

"Greet each other with a kiss of love."

I Peter 5.14

Hospitality is a hot topic in churches today. What I'm trying to contribute in these posts is a look at the micro-level, the non-verbals that subtly send messages like "You're not welcome here." or "I honor you."

In my last post I gave an apology for paying attention to touch. In short, I think touch is an oft overlooked means by which we send signals of hospitality.

Apparently, the early church greeted each other with "a holy kiss" or "a kiss of love." I have no idea what this looked like or how offering the kiss across sociological lines would have been experienced in the early church. My hunch is that as social elites and slaves gathered in the early Christian churches the sharing of a holy kiss would have been a radically subversive gesture, an egalitarian symbol enacted by the body of believers.

We don't kiss in America, but we do have our own form of greeting: The handshake. Like the holy kiss, the handshake is an egalitarian gesture. Two people face each other, touch, and engage in a shared movement. My favorite bit of handshake lore involves Thomas Jefferson. The first two Presidents--George Washington and John Adams--used the Old World practice of bowing to greet visitors and guests at formal engagements. Further, given the status of the Presidency, people bowed to the first two presidents. Jefferson, however, shunning displays of hierarchy and royalty, began to greet his guests with the handshake. This was scandalous at the time as it involved physical touch and, as we have noted, it introduced an egalitarianism in greetings. Jefferson didn't want to be bowed to. This set an egalitarian precedent in America. If you didn't bow to the Highest Office in the Land, well, you didn't have to bow to anyone in America.

So I respect the handshake. It introduced both touch and egalitarianism to American greetings. To this day my favorite part of the Catholic Mass is the rite of peace when you turn to those around you and offer the peace, usually a handshake offered with the words "Peace be with you."

And yet, despite all this, I often find the handshake a bit distant. I guess I pine for the days of the holy kiss. This feeling might be due to my experience in South America a few years ago. In South America (but not only there) both men and women exchange cheek kisses. As an American I initially felt awkward with this act. That is until I experienced it in church. From then on I was sold on the idea of cheek kissing as a greeting, between both men and women.

But until American customs change I think we are going to be stuck with the handshake. So, I do the next best thing. I supplement my handshakes with additional points of contact. Sometimes I'll shake hands with two hands. Sometimes I'll touch the person's shoulder or elbow with my left hand as I shake with my right. Again, all of this is simply to send a clear non-verbal signal of welcome. And, obviously, there are hugs for people I know well.

Now I'll admit that males hugging can be awkward at times. Too much homophobia I guess. So what males need in America is something that is more than a handshake and less than a hug. Here is my recommendation for male greetings in the church:

My favorite male greeting is one I find most common in my African-American students. To start, we all know what the typical handshake looks like:

But in the form of greeting I'm recommending rather than extending the hand outward, the hand is elevated with the elbow bent. Like in this picture of Shaq and Kobe:

From there the hands come together to clasp around the base of the thumbs. Like this:

This posture allows for an embrace. In the classic handshake the arms of the people shaking hands act as a kind of rigid rod between them. It is very hard to move into a hug from a classic handshake. This, I think, is the source of much male-to-male awkwardness when there is a miscue on if we are attempting to shake hands or have a hug.

But from this different handclasp the elbows are already bent. This allows the two people to move quite close to each other, with the hands pressed between the chests and below the chin. To finish off the greeting, after clasping hands, you move in close, and then, with the left arm, reach around the person and offer an embrace. Sometimes it's just a strong pat on the back. You can then back up, still clasping hands.

When I greet my male students this is my preferred mode of greeting and welcoming. The handshake is too distant; the hug is too intimate. But this half hug, half handshake is the perfect mix. Plus, it has a kind of urban cool which I also like.

The Non-Verbals of Welcome: Part 1, Contact Comfort and Healing

After posting about the Free Hugs Campaign, I thought I'd devote a couple of posts to the non-verbals of welcome.

After posting about the Free Hugs Campaign, I thought I'd devote a couple of posts to the non-verbals of welcome.

As I've written about before, I find the constellation of ideas surrounding welcome, embrace, and hospitality to be central to living humanely (which I equate with living Christianly).

The are many facets to welcome. In these posts I want to dwell on how, in passing encounters, I can signal welcome with my non-verbal behaviors. The idea here is to pay attention to how I send signals to others that might subtly enhance or diminish the dignity of the people I encounter.

In Part 2 the first non-verbal I want to consider is touch. But first, in this post, I want to offer an apology for touch and for a general consideration of the non-verbals of welcome.

I want to do this by telling the story of Harry Harlow and his surrogate mother studies, some of the most famous work in the history of psychology. But to fully understand the impact of Harlow's work we'll need to back up and describe the impact of behaviorism upon American parenting.

In the first half of the 20th Century Europe was being dominated by Freud's psychoanalysis. But in America the psychological scene was dominated by behaviorism, led by the work and advocacy of psychologists such as B.F. Skinner and John Watson. Behaviorism was dominated by the ideas of association and contingent rewards and punishment. According to behaviorism, animals, humans included, were born as blank slates, indifferent learning machines that acquired behavioral repertoires through associations ("If I touch a hot oven my finger hurts.") and contingent outcomes to behaviors, such as rewards and punishment.

Now this whole school of thought placed enormous burdens upon parents. If the parent was adept at structuring the associative and reward/punishment milieu of the child's life then the child would turn out well. If the the parent was inattentive or botched this job then the child would come out wrong. Sadly, this behavioral model of parenting received support from the biblical injunction "Train up a child in the way he should go and when he is old he will not depart from it." Parenting was destiny.

If this weren't bad enough behaviorism also undermined the very notion of parental love and affection. It did this in two ways. First, according to the behaviorists if a child was hurt, crying or distressed the parent was not to hold or soothe the child. The behavioral logic here seemed impeccable: If you pick up and comfort a child when he is crying then you, unwittingly, reinforce the crying. Comforting a child was believed to weaken or undermine the character of the child. In the language of the time you would be "spoiling" the child.

The second way behaviorists undermined the parent/child bond was by offering a reinforcement model for the maternal attachment bond. Specifically, why do children attach/bond with their mothers? Behaviorists, given their theory, looked for an explanation in associations and rewards. Given that mothers were the source of breast milk the argument went that children bonded with mothers because mothers were associated with food.

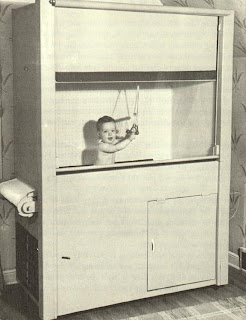

The sum total effect of behaviorism upon American parenting was to create a kind of scientifically sanctioned distance between parents and children. Parenting manuals prior to the 1960s strongly encouraged American parents to not hold or coddle their children, especially when the child was distressed. Children needed to be trained to be autonomous and independent. But what about the desire of the child to be held by the mother? The child sure seems to be expressing a need to be held. Well, it was argued, this wasn't a big deal, the need for a hug was simply a food association acquired during infancy. Nothing really emotional or affectionate to it. This situation got so weird, B.F. Skinner, the leading American behaviorist, developed his infamous air crib to raise children in:

Skinner presented his air crib to American parents in October 1945 in the magazine The Ladies Home Journal in an article entitled "Baby in a Box." Pictured above is Skinner's own daughter, Deborah, who was raised in the box. Happily, in her autobiographical essay, "I Was Not a Lab Rat", she reports suffering no long term psychological damage.

Into this world of "spoiling" and "babies in a box" stepped Harry Harlow. It could be argued that Harry Harlow single handedly brought down the influence of behaviorism in America. Harlow's work certainly changed American parenting. Nowadays most American parents have no hesitation to pick up their distressed child. You can credit all that parental hugging, holding, and cuddling to Harry Harlow.

Here was the the basic design of Harlow's famous study. It involved infant monkeys separated from their mothers. These infant monkeys were released into an area where there were two artificial "surrogate" mothers. One "mother" was made of wire but had a nipple where the baby monkey could get milk. The other "mother" was made of soft cloth and had a heating coil. It was warm and cuddly. The research question was this: Which mother would the infant attach to?

As noted above, behavioral theory had a clear prediction: The infant would attach to the wire mother that provided food. But an unexpected thing happened. The baby attached to the warm, soft mother. Why? What could be more important than food?

Harlow coined the term contact comfort to describe his findings. That is, primates and other animals appear to have an innate need for comforting physical touch. It is this need for contact comfort that drives our most intimate attachments and sits at the heart of affection, love and care-taking. In short, at its most primal core love is physical contact and warmth.

Here is some old footage of Harlow and his research:

Harlow eventually became the president of the American Psychological Association and, in front of a convention filled with behaviorists, delivered his famous President's address The Nature of Love, a speech that fundamentally changed psychology. Love was back. Doctors and pediatricians took notice and parenting manuals began to reflect the new scientific consensus: Touch matters. Suddenly, the work of writers such as Dr. Spock, once considered out of the mainstream, was now backed by cutting edge science. Mothers were now told to trust their instincts and to act upon the natural impulse to hug and hold their children. Cuddling was back with a vengeance. And, sad to say for Skinner's entrepreneurial efforts, air cribs never caught on.

In my next post I want to talk about touch. In this post I simply wanted to tell the story of how psychologists came to recognize how touch is central to the psychology of affection, love, and intimacy. We have an innate need to be touched. It is the most direct and emotional means to signal connection, acceptance, and solidarity. I'm reminded of this when I read this story in the bible from Matthew 8:

When Jesus came down from the mountainside, large crowds followed him. A man with leprosy came and knelt before him and said, "Lord, if you are willing, you can make me clean." Jesus reached out his hand and touched the man. "I am willing," he said. "Be clean!" Immediately he was cured of his leprosy.

I'm always struck by the sequence: Touch then healing. Touch came first. And I always imagine Jesus holding this touch for a time in silence. Because that touch occurs while the man is still unclean. The sequence isn't healing followed by touch. That sequence would signal something completely different, that I won't touch you until you are acceptable and "cleaned up." So as I imagine Jesus holding this touch I can sense that something deep inside the man is being healed irrespective of his leprosy. Something deep, emotional and human is being reached and mended prior to any mere physical healing. The true healing, as I see it, comes with the primacy of the touch. It heals the social dislocation and social alienation associated with leprosy in that time and place, by far the most painful and dehumanizing symptom of the disease.

In short, touch heals. It is the most primal act of love at our disposal.

The Free Hugs Campaign: Things I'm Interested In (Installment #5)

As of this writing, 36,518,483 people have viewed the Free Hugs Campaign (official website here, Wikipedia article here) video on YouTube. I got curious about the Free Hugs Campaign last semester when I ran into (and got a free hug) from some Free Hug Campaigners in our campus center.

For regular readers who think I'm cynical and cerebral you'll be shocked to know that I am, in some way I can't describe, actually touched by the Free Hug idea. (It's the same part of me that likes this WalMart video.)

Actually, I'm in two minds about Free Hugs. A part of me thinks it's kind of odd, sentimental, needy, and corny. I'm always wondering about the motivation of the person giving the hugs.

But there is another part of me, the part that knows how much heart crushing loneliness there is in this world, that loves the simple humanity of the idea. This is particularly the case when I see people imitate the idea. For example, here is a young man in Mexico holding up his Abrazos Gratis sign:

You can see 882 more videos like this on YouTube.

For my hard bitten and cynical readers, I'll be back next week. But for day, well, how about a free hug?

Hell and Cognitive Development

I was recently directed to a post by Keith DeRose, Yale professor, regarding the psychological impact of believing in hell, particularly upon children. The part of Keith's post that grabbed my attention was his psychological theory as to why hell so terrorizes children under the age of 12:

I was recently directed to a post by Keith DeRose, Yale professor, regarding the psychological impact of believing in hell, particularly upon children. The part of Keith's post that grabbed my attention was his psychological theory as to why hell so terrorizes children under the age of 12:

By 12, I wasn't any longer really terrorized by hell, though I still accepted a very nasty, traditional doctrine of hell - as I did all the way into my early 20s. (When I accepted the doctrine but was no longer terrorized by it, I did find it curious that I wasn't so terrorized.) Why do some people who accept a traditional doctrine of hell experience debilitating terror of it, while others don't? Why was I terrorized at 7, but not at 12? Why does debilitating terror tend to occur among children (though some adults also suffer from it)? These are questions that I hope receive some serious investigation. (And, again, if anyone knows of any studies of this, please let me know.) All I can do is provide my own (non-expert) guess, which is based just on my own case and that of several other people I've talked to.

My guess is that debilitating terror of hell is (at least often) explained by the subject getting or having one cognitive ability before or without having another (or having one of them to a much greater extent before or without having the other to a significant enough extent): Having the ability to understand and appreciate the doctrine without (yet) having developed the ability to "quarantine" threatening "beliefs" from having the effects beliefs of that content in some sense should have. (Since this - and especially my use of "quarantine" - is all very vague, perhaps this shouldn't even be thought of an explanation so much as my guess as to the form that the right explanation will take.)

I think Keith is correct in his theory. Although I know of no formal empirical tests of his hypothesis, his argument does fit with what we know concerning childhood cognitive development.

What I think is happening is this. According to Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development, children around the ages of 7 to 11 are in the Concrete Operations phase of cognitive development. In this phase of development children begin to develop logical abilities but without the ability for abstraction. To understand the difference view the following YouTube clip:

Note the answers the children give when in the Concrete Operations stage:

Q: What would life be like if you had no thumbs?

A: You would only have four fingers.

A: You couldn't give someone a thumbs up.

A: You couldn't thumb wrestle.

Those answers are fine, but very concrete. Very tied to physical particulars. By contrast, the adolescent at the end of the clip is in the Formal Operations stage where abstract reasoning comes into its own. Thus, we see the Formal Operations child give a very abstract answer, an analogy between being without thumbs and living life as a left-handed person.

Going back to Keith's post, my hunch is that hell is most terrifying for children in the Concrete Operations stage. In this stage children have the concrete, logical ability to work out the calculus of salvation and damnation. Abstractions such as grace are beyond them, cognitively speaking. A concrete punishment/reward calculus better suits the cognitive stage they are in. And by doing the theological math unattenuated by abstractions such as grace most Concrete Operational children conclude they are doomed to hell.

Worse, they don't think of hell in abstract terms (e.g., "separation from God"). They think of hell in concrete, brutally physical images. Think back to the YouTube clip. What would life be like if you had no thumbs? You'd only have four fingers. You can see how that reasoning would play out concerning hell. What is hell like? It's a place of burning fire. In short, Concrete Operational children are not thinking of hellfire metaphorically or as an abstraction. They are thinking of the fire concretely, as fire. Literally. I doubt, once into the Formal Operations stage, many people see hell as being literally a place of fire. True, they don't imagine it as a day at the beach, but they don't concretely imagine that they will be able to smell their own flesh burning. They know hell will be bad, but they understand hellfire to be an abstraction and that understanding grants a bit of emotional distance. I think it is this distance that is the mechanism behind Keith's postulate of a quarantining ability.

All this is a guess of mine, an application of Piaget's stages to Keith's observations. Empirical laboratory work would be needed to really nail this down.

Certainty and Dogmatism: The Feeling of Knowing

One of my personal and professional preoccupations is trying to understand religious dogmatism. Specifically, I'm interested in understanding the root causes of doctrinal stubbornness and insularity. For example, in my own religious tradition I've sat through endless doctrinal debates regarding church practices. And as I've witnessed these debates I've made the following observation: There are two kinds of people in the world: Those who might change their minds and those who won't.

One of my personal and professional preoccupations is trying to understand religious dogmatism. Specifically, I'm interested in understanding the root causes of doctrinal stubbornness and insularity. For example, in my own religious tradition I've sat through endless doctrinal debates regarding church practices. And as I've witnessed these debates I've made the following observation: There are two kinds of people in the world: Those who might change their minds and those who won't.