How do we account for greed in a Malthusian world?

How do we account for greed in a Malthusian world?

In my last post I argued that the root cause of human sinfulness is living as biodegradable creatures in a world of potential scarcity. This situation makes the human species feel vulnerable and anxious.

But how can this model explain human acquisitiveness in times of plenty? Why is corporate greed rampant in capitalistic economies? Where does greed come from if we are well off? How can Malthus explain American consumerism? Don't we have to posit some kind of intrinsic selfishness to explain all this?

No doubt we are selfish. But again, I'd like to argue that the selfishness gets into us from the outside, from the Malthusian context.

Why are we so acquisitive? An Augustinian treatment would claim that it is due to some intrinsic defect, Original Sin. I've argued that a better place to look for an answer is in the Malthusian predicament humans find themselves in. In short, is human acquisitiveness best explained by an appeal to intrinsic human "selfishness" or by examining how acquisitiveness might be a perfectly logical response to surviving in a Malthusian world?

So, let's ask one more time: Why are humans so acquisitive? The answer, obviously, is that humans discount the future hyperbolically.

You probably want me to unpack that.

To start, it is a fact that we discount the future. As they say, a bird in the hand is better than two in the bush. An immediate reward is more valuable than a delayed reward, even if that delayed reward has a higher value. For example, let's say I offer you a choice:

Choice A: $100

Choice B: $200

Which would you choose? Well, any idiot can make that choice. Okay, then, how about this choice:

Choice A: $100 right now

Choice B: $200 a year from today

Most people take the $100 right now. Why? They discount the future. Although $200 is, in absolute value, more than $100 it is not as valuable in relative terms because it is one year in the future. The $200 has been discounted and is now perceived as less valuable than the $100.

How much less? Well, that is an important psychological question. The issue of human acquisitiveness rests upon how steeply humans discount the future. Let me try to illustrate this. Choice A is $100 right now. Next, I'll offer a variety of choices for Choice B, each at a different time horizon. Look through the list and decide when you'd move from Choice A ($100 right now) to one of the following:

Choice B:

a) $200 a year from today

b) $200 six months from today

c) $200 three months from today

d) $200 one month from today

e) $200 two weeks from today

f) $200 one week from today

g) $200 three days from today

h) $200 one day from today

i) $200 12 hours from now

h) $200 one hour from now

i) $200 30 minutes from now

j) $200 one minute from now

h) $200 right now

At what point, (a) through (h), do you pick Choice B?

As we noted, at time offerings around (a)-(c) people would rather just take the $100 than wait so long for $200. They discount the future. Conversely, when we look at time offerings around (i)-(j) it seems pretty easy to wait a bit for the $200. That is, as the time horizon for the offer approaches the present the discounting is less and less. We see the $200 as $200 and, thus, prefer it to $100.

In short, time and value are inversely related: Immediate payoffs are more valuable than distant ones. As the offer moves away from us in time we increasingly discount it. As it approaches us in time the discount decreases.

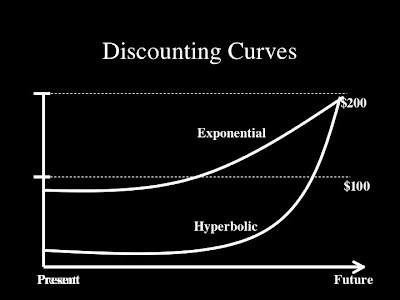

The question for psychologists is what does this discount curve look like? How much do people discount the future? What we are looking for is the shape of what is known as the "discounting curve."

Simplifying greatly, the discounting curve can take one of two shapes. It can be either exponential or hyperbolic in shape. The difference between the exponential and hyperbolic discounting curves is simply this:

If people start moving to Choice B early in the example above--in the (a)-(d) range--then they are discounting the future, but not very much. The discounting curve is shallow (i.e., exponential).

If people start moving to Choice B very late in the example above--in the (e)-(h) range--then they dramatically discount the future. The discounting curve is steep (i.e., hyperbolic).

If you want a graphical representation of what is going on, I made this slide to illustrate the two curves:

Value is on the horizontal axis and Time is on the vertical axis. The graph shows the value of $100 right now (Present) and $200 offered some time in the future. The graph shows that the future is discounted: The curves representing the value of the $200 are both below (i.e., less valued) the $100 being offered right now. The interest of the graph is in how the curves behave as we move through time, left to right. If you put your finger on the exponential curve starting at the left and moving to the right you notice that very quickly your figure goes above the $100 line. That is, the exponential line discounts the future but not by much. The "true value" of the $200 is quickly experienced and preferred. By contrast, if you trace the hyperbolic curve you remain under the $100 line longer. We are steeply discounting the future on this curve. The $200 offer only takes on its true value when the offer is immediately at hand.

Graphs aside, the sum of the matter is this: If people are exponential discounters then we can wait. If we are hyperbolic discounters then we can't wait.

What does all this have to do with human acquisitiveness? Well, the scientific consensus, from scores of studies on this topic, is that humans discount the future hyperbolically. We prefer a bird in the hand to two in the bush. Smaller and immediate rewards are seen as more valuable than larger more distant rewards.

It is the hyperbolic discounting curve that sits behind what the Greeks called akrasia, or "weakness of will." Specifically, we find it difficult to reach our long-term goals because we discount the future so steeply. We give in to short-term temptations, even when we know that the short-term payoff is less valuable than the long-term goal. It's all driven by the hyperbolic discounting.

Why, it might be asked, are we so weak-willed? Why do we discount hyperbolically? The answer brings us back to Malthus. In a time of plenty our hyperbolic discounting psychology is maladapted. We eat too much, spend too much, consume too much. It is hard to save, hard to wait. But evolutionary psychologists have argued that a hyperbolic discounting curve would have been ideally suited to life during human pre-history. That was an age characterized by food scarcity, famine, and a lack of food preservation technology. In those stone age cultures if a large food source was found (e.g., a mammoth kill, berries in season) then gorging yourself has a kind of adaptive logic. Tomorrow, the food will be either gone or spoilt. In that world, a bird in the hand is truly better than two in the bush. Consume the resources now while you have the chance. Who knows what tomorrow might bring?

The point is, all this human acquisitiveness--the gluttony, the akrasia, the consumerism--isn't due to an intrinsic Augustinian defect. It is, rather, an adaptation that humans acquired through eons of struggling in the Malthusian situation. And with this understanding of the psychological machinery we can now explain a wide variety of phenomena from failing to stay on a diet to credit card debt to corporate greed.

It's all the logical outcome of hyperbolic discounting, a trait ideally suited to existence in a Malthusian world.

Next Post: Part 3

Email Subscription on Substack

Richard Beck

Welcome to the blog of Richard Beck, author and professor of psychology at Abilene Christian University (beckr@acu.edu).

Welcome to the blog of Richard Beck, author and professor of psychology at Abilene Christian University (beckr@acu.edu).

The Theology of Faërie

The Little Way of St. Thérèse of Lisieux

The William Stringfellow Project (Ongoing)

Autobiographical Posts

- On Discoveries in Used Bookstores

- Two Brothers and Texas Rangers

- Visiting and Evolving in Monkey Town

- Roller Derby Girls

- A Life With Bibles

- Wearing a Crucifix

- Morning Prayer at San Buenaventura Mission

- The Halo of Overalls

- Less

- The Farmer's Market

- Subversion and Shame: I Like the Color Pink

- The Bureaucrat

- Uncle Richard, Vampire Hunter

- Palm Sunday with the Orthodox

- On Maps and Marital Spats

- Get on a Bike...and Go Slow

- Buying a Bible

- Memento Mori

- We Weren't as Good as the Muppets

- Uncle Richard and the Shark

- Growing Up Catholic

- Ghostbusting (Part 1)

- Ghostbusting (Part 2)

- My Eschatological Dog

- Tex Mex and Depression Era Cuisine

- Aliens at Roswell

On the Principalities and Powers

- Christ and the Powers

- Why I Talk about the Devil So Much

- The Preferential Option for the Poor

- The Political Theology of Les Misérables

- Good Enough

- On Anarchism and A**holes

- Christian Anarchism

- A Restless Patriotism

- Wink on Exorcism

- Images of God Against Empire

- A Boredom Revolution

- The Medal of St. Benedict

- Exorcisms are about Economics

- "Scooby-Doo, Where Are You?"

- "A Home for Demons...and the Merchants Weep"

- Tales of the Demonic

- The Ethic of Death: The Policies and Procedures Manual

- "All That Are Here Are Humans"

- Ears of Stone

- The War Prayer

- Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Experimental Theology

- Eucharistic Identity

- Tzimtzum, Cruciformity and Theodicy

- Holiness Among Depraved Christians: Paul's New Form of Moral Flourishing

- Empathic Open Theism

- The Victim Needs No Conversion

- The Hormonal God

- Covenantal Substitutionary Atonement

- The Satanic Church

- Mousetrap

- Easter Shouldn't Be Good News

- The Gospel According to Lady Gaga

- Your God is Too Big

From the Prison Bible Study

- The Philosopher

- God's Unconditional Love

- There is a Balm in Gilead

- In Prison With Ann Voskamp

- To Make the Love of God Credible

- Piss Christ in Prison

- Advent: A Prison Story

- Faithful in Little Things

- The Prayer of Jabez

- The Prayer of Willy Brown

- Those Old Time Gospel Songs

- I'll Fly Away

- Singing and Resistence

- Where the Gospel Matters

- Monday Night Bible Study (A Poem)

- Living in Babylon: Reading Revelation in Prison

- Reading the Beatitudes in Prision

- John 13: A Story from the Prision Study

- The Word

Series/Essays Based on my Research

The Theology of Calvin and Hobbes

The Theology of Peanuts

The Snake Handling Churches of Appalachia

Eccentric Christianity

- Part 1: A Peculiar People

- Part 2: The Eccentric God, Transcendence and the Prophetic Imagination

- Part 3: Welcoming God in the Stranger

- Part 4: Enchantment, the Porous Self and the Spirit

- Part 5: Doubt, Gratitude and an Eccentric Faith

- Part 6: The Eccentric Economy of Love

- Part 7: The Eccentric Kingdom

The Fuller Integration Lectures

Blogging about the Bible

- Unicorns in the Bible

- "Let My People Go!": On Worship, Work and Laziness

- The True Troubler

- Stumbling At Just One Point

- The Faith of Demons

- The Lord Saw That She Was Not Loved

- The Subversion of the Creator God

- Hell On Earth: The Church as the Baptism of Fire and the Holy Spirit

- The Things That Make for Peace

- The Lord of the Flies

- On Preterism, the Second Coming and Hell

- Commitment and Violence: A Reading of the Akedah

- Gain Versus Gift in Ecclesiastes

- Redemption and the Goel

- The Psalms as Liberation Theology

- Control Your Vessel

- Circumcised Ears

- Forgive Us Our Trespasses

- Doing Beautiful Things

- The Most Remarkable Sequence in the Bible

- Targeting the Dove Sellers

- Christus Victor in Galatians

- Devoted to Destruction: Reading Cherem Non-Violently

- The Triumph of the Cross

- The Threshing Floor of Araunah

- Hold Others Above Yourself

- Blessed are the Tricksters

- Adam's First Wife

- I Am a Worm

- Christus Victor in the Lord's Prayer

- Let Them Both Grow Together

- Repent

- Here I Am

- Becoming the Jubilee

- Sermon on the Mount: Study Guide

- Treat Them as a Pagan or Tax Collector

- Going Outside the Camp

- Welcoming Children

- The Song of Lamech and the Song of the Lamb

- The Nephilim

- Shaming Jesus

- Pseudepigrapha and the Christian Witness

- The Exclusion and Inclusion of Eunuchs

- The Second Moses

- The New Manna

- Salvation in the First Sermons of the Church

- "A Bloody Husband"

- Song of the Vineyard

Bonhoeffer's Letters from Prision

Civil Rights History and Race Relations

- The Gospel According to Ta-Nehisi Coates (Six Part Series)

- Bus Ride to Justice: Toward Racial Reconciliation in the Churches of Christ

- Black Heroism and White Sympathy: A Reflection on the Charleston Shooting

- Selma 50th Anniversary

- More Than Three Minutes

- The Passion of White America

- Remembering James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman

- Will Campbell

- Sitting in the Pews of Ebeneser Baptist Church

- MLK Bedtime Prayer

- Freedom Rider

- Mountiantop

- Freedom Summer

- Civil Rights Family Trip 1: Memphis

- Civil Rights Family Trip 2: Atlanta

- Civil Rights Family Trip 3: Birmingham

- Civil Rights Family Trip 4: Selma

- Civil Rights Family Trip 5: Montgomery

Hip Christianity

The Charism of the Charismatics

Would Jesus Break a Window?: The Hermeneutics of the Temple Action

Being Church

- Instead of a Coffee Shop How About a Laundromat?

- A Million Boring Little Things

- A Prayer for ISIS

- "The People At Our Church Die A Lot"

- The Angel of Freedom

- Washing Dishes at Freedom Fellowship

- Where David Plays the Tambourine

- On Interruptibility

- Mattering

- This Ritual of Hallowing

- Faith as Honoring

- The Beautiful

- The Sensory Boundary

- The Missional and Apostolic Nature of Holiness

- Open Commuion: Warning!

- The Impurity of Love

- A Community Called Forgiveness

- Love is the Allocation of Our Dying

- Freedom Fellowship

- Wednesday Night Church

- The Hands of Christ

- Barbara, Stanley and Andrea: Thoughts on Love, Training and Social Psychology

- Gerald's Gift

- Wiping the Blood Away

- This Morning Jesus Put On Dark Sunglasses

- The Only Way I Know How to Save the World

- Renunciation

- The Reason We Gather

- Anointing With Oil

- Incarnations of God's Mercy

Exploring Preterism

Scripture and Discernment

- Owning Your Protestantism: We Follow Our Conscience, Not the Bible

- Emotional Intelligence and Sola Scriptura

- Songbooks vs. the Psalms

- Biblical as Sociological Stress Test

- Cookie Cutting the Bible: A Case Study

- Pawn to King 4

- Allowing God to Rage

- Poetry of a Murderer

- On Christian Communion: Killing vs. Sexuality

- Heretics and Disagreement

- Atonement: A Primer

- "The Bible says..."

- The "Yes, but..." Church

- Human Experience and the Bible

- Discernment, Part 1

- Discernment, Part 2

- Rabbinic Hedges

- Fuzzy Logic

Interacting with Good Books

- Christian Political Witness

- The Road

- Powers and Submissions

- City of God

- Playing God

- Torture and Eucharist

- How Much is Enough?

- From Willow Creek to Sacred Heart

- The Catonsville Nine

- Daring Greatly

- On Job (Gutiérrez)

- The Selfless Way of Christ

- World Upside Down

- Are Christians Hate-Filled Hypocrites?

- Christ and Horrors

- The King Jesus Gospel

- Insurrection

- The Bible Made Impossible

- The Deliverance of God

- To Change the World

- Sexuality and the Christian Body

- I Told Me So

- The Teaching of the Twelve

- Evolving in Monkey Town

- Saved from Sacrifice: A Series

- Darwin's Sacred Cause

- Outliers

- A Secular Age

- The God Who Risks

Moral Psychology

- The Dark Spell the Devil Casts: Refugees and Our Slavery to the Fear of Death

- Philia Over Phobia

- Elizabeth Smart and the Psychology of the Christian Purity Culture

- On Love and the Yuck Factor

- Ethnocentrism and Politics

- Flies, Attention and Morality

- The Banality of Evil

- The Ovens at Buchenwald

- Violence and Traffic Lights

- Defending Individualism

- Guilt and Atonement

- The Varieties of Love and Hate

- The Wicked

- Moral Foundations

- Primum non nocere

- The Moral Emotions

- The Moral Circle, Part 1

- The Moral Circle, Part 2

- Taboo Psychology

- The Morality of Mentality

- Moral Conviction

- Infrahumanization

- Holiness and Moral Grammars

The Purity Psychology of Progressive Christianity

The Theology of Everyday Life

- Self-Esteem Through Shaming

- Let Us Be the Heart Of the Church Rather Than the Amygdala

- Online Debates and Stages of Change

- The Devil on a Wiffle Ball Field

- Incarnational Theology and Mental Illness

- Social Media as Sacrament

- The Impossibility of Calvinistic Psychotherapy

- Hating Pixels

- Dress, Divinity and Dumbfounding

- The Kingdom of God Will Not Be Tweeted

- Tattoos

- The Ethics of :-)

- On Snobbery

- Jokes

- Hypocrisy

- Everything I learned about life I learned coaching tee-ball

- Gossip, Part 1: The Food of the Brain

- Gossip, Part 2: Evolutionary Stable Strategies

- Gossip, Part 3: The Pay it Forward World

- Human Nature

- Welcome

- On Humility

Jesus, You're Making Me Tired: Scarcity and Spiritual Formation

A Progressive Vision of the Benedict Option

George MacDonald

Jesus & the Jolly Roger: The Kingdom of God is Like a Pirate

Alone, Suburban & Sorted

The Theology of Monsters

The Theology of Ugly

Orthodox Iconography

Musings On Faith, Belief, and Doubt

- The Meanings Only Faith Can Reveal

- Pragmatism and Progressive Christianity

- Doubt and Cognitive Rumination

- A/theism and the Transcendent

- Kingdom A/theism

- The Ontological Argument

- Cheap Praise and Costly Praise

- god

- Wired to Suffer

- A New Apologetics

- Orthodox Alexithymia

- High and Low: The Psalms and Suffering

- The Buddhist Phase

- Skilled Christianity

- The Two Families of God

- The Bait and Switch of Contemporary Christianity

- Theodicy and No Country for Old Men

- Doubt: A Diagnosis

- Faith and Modernity

- Faith after "The Cognitive Turn"

- Salvation

- The Gifts of Doubt

- A Beautiful Life

- Is Santa Claus Real?

- The Feeling of Knowing

- Practicing Christianity

- In Praise of Doubt

- Skepticism and Conviction

- Pragmatic Belief

- N-Order Complaint and Need for Cognition

Holiday Musings

- Everything I Learned about Christmas I Learned from TV

- Advent: Learning to Wait

- A Christmas Carol as Resistance Literature: Part 1

- A Christmas Carol as Resistance Literature: Part 2

- It's Still Christmas

- Easter Shouldn't Be Good News

- The Deeper Magic: A Good Friday Meditation

- Palm Sunday with the Orthodox

- Growing Up Catholic: A Lenten Meditation

- The Liturgical Year for Dummies

- "Watching Their Flocks at Night": An Advent Meditation

- Pentecost and Babel

- Epiphany

- Ambivalence about Lent

- On Easter and Astronomy

- Sex Sandals and Advent

- Freud and Valentine's Day

- Existentialism and Halloween

- Halloween Redux: Talking with the Dead

The Offbeat

- Batman and the Joker

- The Theology of Ugly Dolls

- Jesus Would Be a Hufflepuff

- The Moral Example of Captain Jack Sparrow

- Weddings Real, Imagined and Yet to Come

- Michelangelo and Neuroanatomy

- Believing in Bigfoot

- The Kingdom of God as Improv and Flash Mob

- 2012 and the End of the World

- The Polar Express and the Uncanny Valley

- Why the Anti-Christ Is an Idiot

- On Harry Potter and Vampire Movies

A first reaction is that you are describing immaturity not sin.

I am not an expert theologian. As an ordinary lay person I have to deal with poor understanding in myself and others of complex historical issues from original sin to evolution. I have a friend who is a world renowned expert on twins who substitutes original sin and evolution in conversations. They don't simply substitute for each other though they can be related - neither does a Malthusian resource crunch account for original sin. Where do pragmatics intersect love?

In your last post I thought that the lack which is perceived in the garden by Eve is already sin, a failure to trust the commandment and a failure to trust even herself and her own memory - long before the snake gets into the act. I think you are on the right track distinguishing innocence from righteousness. Innocence is not a desirable end. So when faith expresses itself as in Psalm 23 - I lack nothing, the result is not innocence but trust in the midst of great difficulty. The pre-disobedience state cannot achieve this faith. The post disobedient state gives rise to murder etc as you pointed out but these results have to do with a lack related to the cost of relationship and absolute power.

In this your current post, consumerism can be both positive and negative - both good and evil. The good is in the manufacturer creating value for others. The evil is in the desire of value for free - and more subtly in the manipulation of need and the creation and exploitation of false needs. There is also a failure to understand time - and it is particularly obvious in the examples you give. If you can afford to wait, $200 is better than $100 even after 5 years.

Fear has to be considered in the motivation also. Both consumer and producer can be hamstrung by fear. In the resurrection and even in its promised and maturing form though the anointing (1 John 2:27), perfect love casts out fear (1 John 4) including such pragmatic fears as meeting payroll and achieving good production standards. This is a maturing to be desired but it is not bought for nothing. While the price is paid by the death of Jesus and the means to growth is by that death in the Spirit, the cost to the individual is in the cost of experience and the measure of love that that experience expresses towards others.

It could be said that Jesus in doing away with sin makes us all through his death and resurrection into maturing pragmatic atheists. (The early Christians and Jews were accused of atheism. It fits if you understand 'the gods' as the idols of your own work and your own ideas.)

I've really appreciated these posts on a Malthusian understanding of sin. In fact I think they fit quite well into an understanding of structural sin as being external forms that corrupt the world. I also read it with the narrative of Eden very much in mind and found that Malthus's problem of limited production resonates with God's curse upon the ground that man would hereafter struggle to draw fruit from the ground.

However, I see this all as complimenting the inherent falleness of man. Ignoring Augustine how do you deal with man's internal struggle with sin as described in Romans 7:8-25? Also surely you don't think man enters the world a blank slate unaffected by sin. I saw a bit of a video on Ted refuting blank slate http://www.ted.com/index.php/talks/steven_pinker_chalks_it_up_to_the_blank_slate.html that you might find interesting (he might actually support blank slate theory after the first 5 odd minutes but I was only browsing a couple of videos earlier on for interest). Not that his denial of a blank slate understanding of the mind supports an inherently fallen nature of the mind but he does say that it does somewhat destroy the ideal that man starts pure and through social engineering we may be able to preserve such innocence. From a Christian understanding I can't help but tie this understanding to my own understanding of our sinfullness from birth.

Hi Bob,

No doubt that this account is lacking. And I doubt I can fit a theologically thick description of sin into the Malthusian frame.

But that isn't really my goal. My aim is more modest, to show that a great deal of what we call "sin" isn't due to innate human depravity but, rather, the predictable outcome of living in a Malthusian situation. That doesn't make human action any less evil. Just a reframe on the ultimate source of the evil.

Hi Philip,

No, I don't believe in a blank slate. In fact, this post describes an innate psychological mechanism: Hyperbolic discounting.

Once that innate tendency is in play then we end up with the internal struggles discussed by both Augustine and Paul. I observe how I shoot myself in the foot, sacrificing important long-term goals for short-term pleasures. This is, as both Paul and Augustine note, an internal struggle. But my point is that this internal struggle didn't arise ex nihilo or through one person's bad choice. The internal struggle is the product of an extrinsic Malthusian force that shaped human psychology, creating the innate tendencies that Paul, Augustine, and all all of us struggle against.

In short, I'm not saying that the struggle of sin isn't internal. I'm just asking, how did that struggle get there? In my opinion, the Malthusian pressures of the world are partly to blame.

I think whenever there is a shortage of a given expertise, then there is value and an attempt to manipulate or control that shortage to one's advantage. This is considered shrewdness in the business world...

But, when one chooses to set up a business and risk investments for a future advantage, then that is a decision of choice for the enteprenuer...those who choose not to co-operate with the business risk is not being 'selfish" or greedy or lacking in character, just because he has a larger context to evaluate in deciding whether he can risk and if that is the lifestyle he chooses...it has nothing to do with virtue necessarily. That is a false premise, I think...

So, whether it is in a business endeavor where resources are scarce (financial outlay up front) or the actual needed expertise, then. it is not a question of delayed gratification, which will result in character training, etc...that is a false "set-up" which presupposes a LOT...

Another example in the "Overdressed Ape", is the need for territory and what transpires because of the desire for terrotory. There is nothing innately wrong about terroritory, it is in the asqusition, attainment, focus on, etc. when it becomes a problem. But these issues are ones not so easily addressed from the outside, unless one wants a communistic system...

Hi Richard, I'm really enjoying these latest posts, but I do wonder what your Malthusian view of sin does to our view of God.

What I mean is, if sin is not something that humans - or other free agents - brought into the world (so to speak), but rather is our response to the world, then what does that say about God, as the creator of that world?

Limiting sin to a response makes it seem as though God, the creator, is the one who is ultimately responsible for humanity's "fall." Unless I missed the spot where you hold humanity accountable somehow for our response to Malthusian forces.

It seems that the Christian faith, properly conceived, has to hold in tension God's freedom with human freedom (i.e. Christian determinism doesn't seem to be a valid option, IMO). But this leads to a host of conundrums.

I know Hick and others view sin as something that humanity will eventually "outgrow" as we become what God intends us to be, but that seems to sidestep the issue of: what kind of God is that? It seems to lead directly toward a God who is not omnipotent or omniscient, which for some is just fine. I'm not so sure.

Anyway, I know that's a whole different can of worms, but I thought I'd open it. :-)

I think I'm in the same camp as Geoff, insofar as creation's Malthusian character forms in us traits that lead to sin, or are sinful in themselves. At the very least, it seems like for this project to work you have to provide an account of creation that does not leave out God without indicting him directly for sin, evil, injustice, etc.

I am also wondering what the overall point, so to speak, of concluding that "external" factors are primarily (you've specified you don't mean solely) responsible for our potentially sinful characteristics (such as human acquisitiveness). How can we know, or why might we conclude, that the Malthusian world formed in us then-proper but now-unhelpful/sinful traits that have led us to our current situation, rather than or alongside an inner disposition, from birth on or whatever, that sets "myself" up as god (that is, I provide for myself over against others and instead of trusting God)? I guess I am seeing neither the reasons to arrive at your conclusions nor the larger implications, other than being different than what Augustine and Calvin taught.

It is all, however, wonderfully fascinating.

Geoff and Brad,

After musing for how best to respond let me try this.

Rather than give a direct answer (which would be very long) let me specify two of my theological tendencies/commitments/fixations:

#1: I conflate soteriology with theodicy. The "problem of pain" (not human "sinfulness") is the object of God's salvific work. Thus, if you read me a lot, you'll see that I always reframe soteriological concepts--sin, the Fall, grace, salvation--as theodicy issues. For example, in these posts "sin" is being reframed as a theodicy problem (which you both picked up on)

#2: I downplay free will. This, obviously, affects one's theodicy options. If you downplay free will (e.g., Adam's choice) then God takes on more responsibility in creating and redeeming The Mess.

This is why I gravitate toward thinkers who take my two commitments seriously. For example, Hick's work in Evil and the God of Love and McCord Adams' Christ and Horrors.

In short, I don't have a great answer for you both. So here's how I'd approach my thinking: Beck is a guy who has driven two non-negotiable theological stakes into the ground and he's trying to rethink every theological conversation, category, and system in light of those two commitments.

In working with a closed system, you you have to believe in man's choice, which do determine what happens! I cannot see any other way around this one, as whether one believes God works within a moral order, or within scientific theory in application to the moral order, or whether God exists within creation itself and it is just a matter of "manifesting his kingdom"...then, whichever way you view the limitation of free will because of the determining forces of a closed universe...you "fix" by theologizing to the "peasant, scientifically unenligtened"..as in Adam's sin and God redemption of "other men's choices"...

As far as dissolving salvation into theodicity, this is the height ot arrogance, as far as I can tell, because, while those in leadership choose how things will be, whether in government or organizations, you try to sell the "evil" problem as a "exercise of virtue" in forgiveness, humility, submission, et all to the VICTIM of those who have determined what "lot they play in life"!!! That is exactly what Hitler did in his political ideaology!!! but yours ideology is naturalism (sceintism)..(and those pinions, the creationists (jews:)) are to be ostricized, outcasts, and hopefully killed, and you giver them the "good news" of the "gospel"!!!

I have enjoyed reading your blog and will continue to do so, but I cannot accept a determinism in any shape or form...whether naturalism or supernaturalism!!!

Hi Angie,

I'm not quite sure about what you are objecting to. I'm not advocating a determinism. I'm simply suggesting that human will is not omnipotent. We are finite creatures, causally bounded. Which is to say there are causal forces "outside" us. Do those "outside" forces determine our actions? I cannot say. But I do believe we are pushed around quite a bit by those forces. And they are powerful at times. Mighty forces to be reckoned with. Just ask any severely depressed person to "cheer up" and see how that goes.

And, as I noted above in my response to Geoff and Brad, if we own up to the limitations of a finite human volition, well, then that means God is going to have to do that much more. So if, in the end, we blame God more for creation and human suffering, I also believe he will respond and shoulder that blame, take it into his own nature and, at the end of all things, be good, very good, to every created thing.

I had just come back to apologize for my "impertinence"...But, I cannot accept determinsim...and those who do try to control by "fixing" the "problem" (me, as this is an internal message), I do react to...

Forces that impose upon us as humans are the limitations of our understandings, another's choice that impinges upon a boundary, limitations of power, position or authority...these are the things that limit one...but limitation does not mean "God", as in the "blessed controller of all things"...no it means leadership. Bad leaders dominate, control, manipulate, and hinder, while good leaders do otherwise...empower, equip, enlarge, educate, and encourage...

Thanks for the explanation. I'm sure I'll be coming back with more and different questions, but that does clarify quite a few things. I'm still interested in the role of sin (not necessarily "human sinfulness") in theodicy, salvation, redemption, etc., but I'll leave that for another time.

Here's to Part 3.

It also seems that this post is driven not just by a closed system, but also by a "out-come based" ideal. The poor will always be with us, and some think that this means that everyone's focus should be on the poor, that is, if we are "bible believing christians". This is mixing micro-economics and maco-economics. and this is the philosophical distinction between the Republicans and the Democrats...

Richard, others,

This post and its comments are enriching for me. I'll be sorting them out for a while. I'm wondering about all this talk about original sin (I don't find it in the Gospels). Seems we are, ahem, damned if we believe in it and damned if we don't. Which led my imagination (infected with original sin or Malthusian entropic fears) to postulate this double-damned conversation between Adam and Eve prior to Eve listening to the talking snake:

Eve: "Adam, does my birthday suit make my butt look bigger?"

Adam: "I don't know. Maybe the Snake does. Go ask him."

Anyway, maybe we are asking the wrong questions.

George C.