Two years ago I wrote this Advent meditation about cultures of honor and violence, about why the shepherds were "watching their flocks at night" and about why it was such a scandal for shepherds to be the first to hear about the birth of Jesus.

Two years ago I wrote this Advent meditation about cultures of honor and violence, about why the shepherds were "watching their flocks at night" and about why it was such a scandal for shepherds to be the first to hear about the birth of Jesus.

I also explain why it's not a good idea to insult people south of the Mason-Dixon line...

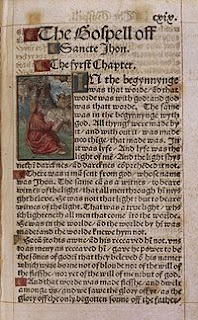

And there were shepherds living out in the fields nearby, keeping watch over their flocks at night. An angel of the Lord appeared to them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were terrified. But the angel said to them, “Do not be afraid. I bring you good news that will cause great joy for all the people. Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign to you: You will find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger.”

Suddenly a great company of the heavenly host appeared with the angel, praising God and saying,

“Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests.”

When the angels had left them and gone into heaven, the shepherds said to one another, “Let’s go to Bethlehem and see this thing that has happened, which the Lord has told us about.”

They hurried to the village and found Mary and Joseph. And there was the baby, lying in the manger.

One of my most favorite psychological studies was published in 1996 by Dov Cohen, Richard Nisbett, Brian Bowdle and Norbert Schwarz in the

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Titled

Insult, aggression, and the southern culture of honor: An 'experimental ethnography' the study attempted to see how Southerners and Northerners in America responded to insult. The authors argued that a "culture of honor" had been, historically, more robust in the Southern United States (due to immigration patterns) making Southerners more sensitive to perceived affronts to their personal honor (e.g., being insulted or disrespected).

To test this theory the researchers asked Northern and Southern college students to come to a building where they were asked to fill out some surveys. After filling out the surveys the subjects were asked to drop them off at the end of a hallway and then return to the room. But the hall was blocked by a filing cabinet, open, and with a person looking through it. To get past this person the subject had to ask this person to close the drawer to make room to pass. The person at the filing cabinet was in on the study and he complies with the subject's request with some annoyance. The subject passes the filing cabinet, drops the surveys off, and then returns back toward the filing cabinet. The person at the filing cabinet has reopened the drawer and is again blocking the hallway. As the subject approaches for a second time this is what happens, quoting directly from the study:

As the participant returned seconds later and walked back down the hall toward the experimental room, the confederate (who had reopened the file drawer) slammed it shut on seeing the participant approach and bumped into the participant with his shoulder, calling the participant an “asshole.”

Sitting in the hallway nearby were raters who looked, ostensibly, like students reading or studying. But what the raters actually did was to look at the face of the subject at the moment the insult occured. They then rated how angry versus amused the subject looked. Because we can expect a wide variety of reactions to the insult. Some of us would smile or laugh it off. Some of us would get angry and seek to aggressively confront the person who just called us an asshole.

The research question was simple: How did the Southerners and Northerners compare when responding to the insult? Was one group more angered or amused?

The findings, consistent with the Southern culture of honor hypothesis, showed that Southerners were more likely to become angered by the insult while Northerners were more likely to become amused. This finding was reconfirmed in a variety of different follow up studies (for example, Southerners had significantly more stress hormones in their body relative to the Northerners after the insult).

All in all, then, it seemed that Southerners were working with, and defending, a more robust "honor code" than Northerners.

But where does a "culture of honor" come from?

One explanation that has gained a lot of attention is a theory posited by Richard Nisbett and Dov Cohen, two of the authors of the insult study, in their book

Culture of honor: The psychology of violence in the South. Specifically, Nisbett and Cohen argue that different ethics of honor and retaliation have evolved in herding versus farming cultures.

The argument goes like this. It's hard to steal from farmers. If I have acres and acres of wheat or corn it's pretty hard for a couple of thieves to make off overnight with the fruits of my labor. More, for large parts of year there really is nothing to steal. There is no crop during the winter, spring and early summer. In short, for most of the year there is nothing the farmer has to guard or protect. And even when there is a crop to steal you can't make off with it overnight. Harvesting is time consuming and labor intensive.

All in all, then, farming cultures, it is argued, have evolved a fairly pacific and non-retaliatory social ethic.

Herding cultures face a very different problem. Imagine a cattle rancher. You can steal cattle much more quickly and efficiently relative to trying to steal a corn harvest. A handful of cattle rustlers can quickly make off with hundreds of cattle, with devastating economic impact upon the rancher. More, the cattle are always around. Unlike the farmer, the rancher's livelihood is exposed 24/7 for 365 days a year. While the farmer sleeps peacefully during the winter months there is no respite for the rancher.

Given these challenges, it is argued that herding cultures have developed a very strong ethic of retaliation. The only way to survive, economically, in a herding culture is to protect your livelihood and honor with lethal vigilance. Farmers, by contrast, are spared all this. And, given these contrasting demands, there has been a lot of data to suggest that herding cultures (or places settled by herding cultures like the American South) are, indeed, more violent than farming cultures.

(For full disclosure, this trend is disputed in the literature with data on both sides of the argument. Studies are still ongoing.)

Even if you don't find this argument compelling you likely recognize the stereotypes from American film. In Western films farmers are rarely violent. They tend to be peaceable. By contrast, ranchers and cowboys tend to be violent. And when someone in Western films has become respectable it's often associated with settling down and taking up the farming life. Conversely, leaving the farm is the resumption of violence. Think of William Munny in

Unforgiven.

Why am I going into all this? Well, during this Advent season we are exposed to many portrayals of the shepherds in Luke 2 as they keep watch over their flocks at night. And these images often look like Hallmark cards. It's sweet and idyllic. Peaceable.

Well, there was a reason these guys were up at night watching their flocks. They are examples of a herding culture. The point being, these shepherds were pretty tough, even violent, men. They aren't into sheep because they are sweet looking props for our Nativity sets. When you see those sheep you should see dollar signs, stock portfolios, walking retirement plans. That's why the shepherds were up at night. If I put your paycheck, in 10 dollar bill increments, in a pile in your front yard I bet you'd be up a night keeping a watch on your flock. Gun in hand.

The point in all this is that these shepherds were likely rough and violent men. They had to be. So it's a bit shocking and strange to find the angels appearing to these men, of all people. Thugs might be standing around in our Nativity sets. That scene around the manger might be a bit more scandalous than we had ever imagined.

But here's the truly amazing part of the story. The angels proclaim to these violent men a message of "peace on earth." And, upon hearing this message, the shepherds

leave their flocks and go searching for the baby! Can you now see how shocking that behavior is? This is something you don't do in a herding culture.

Now think about how all this might apply to us. For most of our lives we stand around protecting what is ours. Our neighborhoods, borders, homes, 401Ks, income, jobs, status, reputation. And on and on and on. We're like those shepherds, keeping watch over our flocks, even at night. We're tensed, suspicious, watchful, and ready to pounce. And all this makes us violent people, in small ways and large. That's the ethic of this world. It's a herding ethic. Protect what is yours because someone is coming to take it from you. It's a culture of honor. And violence.

And so the angels come to us and proclaim "peace on earth and good will to men." But how is that going to happen? Well, the story in Luke 2 shows us the way:

We follow the example of the shepherds. We leave our flocks and our lifestyles of violent vigilance...and go in search of the baby.

.jpg)