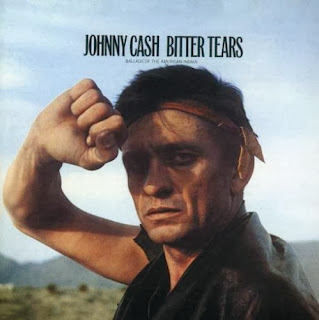

When we talk about Cash's music standing in solidarity with oppressed or marginalized groups I think the best place to start is with Bitter Tears and the tragedy of Native Americans in the United States.

Cash was troubled by the experience of the Native American. So he recorded Bitter Tears to give voice to this tragedy and to throw a light on how our history books have conveniently swept the genocide of Native Americans under the rug.

Given the content of the album Bitter Tears wasn't going to set any sales records. Cash struggled to get anyone to play the songs on the radio. Cash attributed the lack of airplay to moral cowardice and racism.

The album does contain strong stuff. Bitter Tears sounds like it came straight out of Howard Zinn's A People's History of the Untied States. On the album Cash revisits American history, only this time reading history from the perspective of the Native American rather than that of the White man.

For example, Bitter Tears starts off with the song "As Long as the Grass Shall Grow." The song recounts the loss of Seneca nation land in Pennsylvania due to the construction of the Kinzua Dam in the early 1960s. The song begins with the treaty and promises made by the US government giving that land to the Seneca nation. The treaty signed by George Washington gave the land to the Seneca nation forever: "for as long as the grass shall grow and the moon shall rise." But forever really wasn't forever. The treaty was broken, like so many of the treaties signed by the US government with the various Native American nations.

The most shocking song on Bitter Tears is "Custer," a Native American recounting of the death of General Custer at Little Bighorn. The refrain of the song delights in the death of Custer by gloating "the General he don't ride well anymore." The song speaks to how the victors are the ones write the history books: "It's not called an Indian victory but a bloody massacre." And the song ends by taking delight in how Custer's flowing blond hair got scalped:

General George A. Custer, oh his yellow hair had lustreAnd you'll have to listen to the song to hear how Cash chortles with delight when singing about Custer getting scalped. In this song is Cash giving voice to Native American rage. "Custer" is an imprecatory psalm, like Psalm 137:

But the General he don't ride well anymore

For now the General's silent, he got barbered violent

And the General he don't ride well anymore

By the rivers of Babylon we sat and weptThe lament and rage continue in the song "Apache Tears," a song recounting the horrors of the US government forcibly removing Native Americans from their land and marching them to reservations. Thousands died on these "trails of tears." One verse from "Apache Tears" recounts an Indian woman raped to death by drunken soldiers:

when we remembered Zion.

How can we sing the songs of the Lord

while in a foreign land?

Daughter Babylon, doomed to destruction,

happy is the one who repays you

according to what you have done to us.

Happy is the one who seizes your infants

and dashes them against the rocks.

Dead grass, dry roots, hunger crying in the nightI bet you are starting to see why Bitter Tears didn't get much radio airplay.

Ghost of broken hearts and laws are here

And who saw the young squaw, they judged by their whiskey law

Tortured till she died of pain and fear

Where the soldiers lay her back, are the black Apache tears

The most famous song of Bitter Tears is "The Ballad of Ira Hayes." Ira Hayes, a Native American, was one of the five Marines who raised the American flag at Iwo Jima, captured in the iconic photograph. But like so many Native American men, Ira Hayes succumbed to alcoholism upon his return to the States. Ira Hayes, veteran and American hero, died lying in a ditch from exposure and alcohol poisoning.

Finally, the song "White Girl" tells an intimate story about how racism is tied up with sex, romance and marriage. A "white girl" toys around with a Native American man, treating him like an exotic plaything and showpiece. But he really falls in love and proposes marriage. She rejects him on racial grounds. It was fun while it lasted, but it never was in the cards. What was he thinking? A "white girl" would never marry an Indian:

She took me to her partiesSuch are the songs on Bitter Tears, one of Johnny Cash's most courageous albums. Bitter Tears was never going to sell a lot of records, but it stands out for its conviction and conscience. Bitter Tears is an album that speaks about tragedy, suffering and injustice across the spectrum of the Native American experience. This was Johnny Cash trying to give voice to that suffering and prick the conscience of his nation.

She carried me around

And I was a proud one

The tallest man in town

...

Well, when she came to leave me

She took me by the arm

And she said, she loved me

And would not do me harmBut she would not marry

Not an Indian she said

She thanked me for my offer

And I wished that I was dead

Through these songs Johnny Cash tried to draw our hearts and minds toward the bitter tears we had caused, ignored and forgotten.

Part 5: San Quentin You've Been Living Hell to Me

After reading this post I had to go wash myself, so I went to You Tube and watched speeches of Sarah Palin. Whew- I feel better now.

I just went on ebay and bought this cd. It'll be the first Cash album that I've ever bought.

me too (very waylayed). I ordered the book from Amazon; I listened to the whole album on youtube. I'm still amused that I'm just now coming to know this artist/musician/prophet and what he did with his anger.

Nicely gratuitous. Congratulations!

Were it not such an apt critique on some of the Christian culture of our day, I'd agree with you and pull my comment- in fact, I wouldn't have even written it. I felt such a depth of grief reading Cash's lyrics; it let me see how trivial the culture of American Exceptionalism often times is: the light it sheds is more glaring than illuminating.

I have absolutely loved reading along with this series, Richard, as I'm a fan of Johnny Cash! (But I confess I haven't listened to Bitter Tears). I have a few follow-up questions in light of this post, though... You may not be able to answer any of these questions, but I thought they might make for good discussion in the context of theology that advocates for the oppressed.

Basically, I'm curious what his relationship was to the Native American community. (Is he descended from a particular tribe? Did he grow up near a reservation? Did he have Native American friends?) What role, if any, did Native Americans play in bringing the album to fruition? What was the reaction from the different Native American tribes to the album's release?

The theology of the album is no doubt an effort of solidarity with the oppressed, but there's a difference between speaking *with* and speaking *for.* Without the context of his relationship and history with Native American people, it's hard to tell what category his album falls under, especially in light of what perspective he takes as the narrator of each song. Is he an observer or a participant? For example, with his use of Psalm 137 in "Custer," there's a lot of "we" in there. If he's telling the story as a Native American, I wonder about that choice's implications without knowing the context of his relationship to the Native American people.

Methinks that simply tells us more about you than it does about Mrs. Palin, whose devotion to the causes of "the least of these" that are within her reach is well documented for those who can set aside their self-righteousness long enough to see it.

Hi Bethany,

I personally don't know the answer to that question. He may be speaking for. It's also art and may be a act of artistic immersion. Not sure if that makes any difference.

Richard Beck, PhD

Abilene Christian University

ACU Box 28011

Abilene, TX 79699

beckr@acu.edu

325.674.2310

How does my "self righteousness" as you say here, compare to the American Exceptionalism espoused by Sarah Palin et al? To be sure qb, I'm not singling out Sarah Palin at a personal level, and I don't doubt for a moment that she's done terrific things for people in her reach; we all do.

She's placed herself as a figurehead in the minds of American culture- maybe even a symbol. It's at this level where I went with my grief and anger.

Then wonder why the former half governor was so critical of Pope Francis and his demonstration of consideration for the "least of these?" In fact for what the new Pope has shown with his heart and hands, she seeks to discredit him by calling him a "liberal."

In the UK, the Archbishop of Westminster Vincent Nichols has just issued a scathing attack on the brutality of welfare reform in David Cameron’s Coalition government, calling it a “disgrace”. A host of Anglican bishops and other church

leaders have added their own Amosian outrage (ecclesial critiques the likes of which we haven’t seen since responses, e.g., Faith in the City, to Margaret Thatcher’s scorched-earth policies in the eighties). Why? Because, true to form, the Coalition’s legislation on tax and benefit-cuts enriches the already-opulent and deepens the abyss of poverty – homelessness, unemployment, low-pay, rising heating costs and food prices – “Heat or Eat” (hunger, for Christ’s sake, has become an acute problem and food banks proliferate) – of “the least of these”. But Palin and Co. – they make Cameron and Co. look to the left of pre-New Labour socialists! When you examine wealth distribution in the US – big bucks in the hands of the few – Palin’s “'least of these' that are "within her reach" become a grotesque parody of the little ones Jesus is talking about in Matthew 25. Shhh … Do you hear that sound? It’s Johnny Cash turning in his grave.

Dr. Beck, you don't know how much I appreciate this series. Johnny Cash looms large in my world, even if he is only an sound on the vinyl or an image on the screen.

My collection includes (in the original vinyl): Bitter Tears, At Folsom Prison, I Walk the Line, Ring of Fire, Mean as Hell, Orange Blossom Special, and Blood Sweat & Tears. I have a later copy of Holy Land, and modern translations of My Mother's Hymn Book, and American Recordings.

I don't put this list out here to gloat or brag, or to establish a canon, but to demonstrate the potential for influence in my life.

My great-great grandmother was a Cherokee who was married to a Missouri

white man. The marriage was a scandal, and the family did much to scrub

the record of her heritage. To this day, I could not prove my Cherokee

blood to anyone, except for my "red" skin and my dark hair in a family

of blonde whiteys; my blood boils when I hear the stories... the

"history".

My father was a police officer and prison guard until he retired. He worked on a railroad crew for a few years in between. His mother was the strongest spiritual influence in his life. At times my dad drank too much and smoked too much. Cash's influence just oozed from my father. He treated the prisoners in his charge as men, with respect. He grew up poor, just like them. He passed those vinyl records on to me. He passed the ooze on as well.

In spite of my internet avatar, I am a miner. I work alongside men and women who put in grueling hours at labor so dangerous society would deem it cruel and unusual punishment, if we weren't willing and paid. My life is filled with miscreants, losers, and riff-raff, the unwashed and the unloved.

Johnny Cash speaks at a level in my heart and mind, and with an authority that makes me sure we have met and talked like friends--yet I have never met the man. I wept deeply when he died. Maybe it was all an act, a bit that separated him from the other singers in the biz. Somehow I don't think so.

So, Dr. Beck, this series you are writing is not so much "experimental", as it is a description of the real and genuine that faith can be, outside of the sanitized expectations faith is purported to be.

Cash was an apostle of a different sort, a follower of Jesus if ever there was one.

Amen.

And vinyl, and passed down from your father! I have a similar collection, but that's something special.

Hi Bethany,

I finally got home to where I could check Hilburn's recent biography to see what he had to say about Native American involvement with Bitter Tears.

Regarding the song "The Ballad of Ira Hayes" Hilburn writes this:

"[Cash] visted Ira Hayes's mother on the Pima reservation in Arizona. The woman was so touched that she gave Cash a small black stone that became translucent when put under light. Known as an 'Apache tear,' the stone held deep symbolism in the Pima culture, and Cash had it mounted in a gold chain and hung it around his neck. He wore it the day he recorded 'Ira Hayes'."

Also, Cash worked on Bitter Tears with Peter La Farge, another folk singer. Some of La Farge's biography picked up from the Internet:

"Peter La Farge was descended from the Nargaset Indian tribe, which had

virtually ceased to exist by the end of the 19th century. Along with his

sister, he was raised by members of the Tewa tribe on the Hopi

reservation adjacent to Santa Fe, New Mexico. He spent much of his

childhood on a nearby ranch, and was adopted at around age nine by

writer Oliver La Farge, author of the 1930 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel

Laughing Child, which dealt with the Navajo Indians. Father and adopted

son shared a common love for Native American customs and history, and

the two later appeared together at an exhibition of the Hopi Eagle dance

in New York City."

Peter's father would eventually be head of the Association on American Indian Affairs.

Apparently, however, Peter's link to the Nargaset has been disputed.

So, in La Farge Cash (perhaps mistakenly) felt he was working with someone who represented an authentic Native American voice.

There is also a book I found about Cash's recording Bitter Tears:

http://www.amazon.com/Heartbeat-Guitar-Johnny-Making-Bitter/dp/156858637X

Looking through a bit of it online I learned that Cash visited the Rosebud and Pine Ridge Reservations. He also played a standing-room-only benefit concert for the Sioux at Rosebud in '68, but that was four years after the recording of Bitter Tears. Much of the concert was from the album.

So that's what I could find. I'm sure there is more in that book.

You missed one of the best tracks, "Drums", a song that resonates with Canadian natives who are still coming to terms with the residential schools policy even though it's about American experiences.