Violence.

To set out the question right here at the start, this post is about the location of slave revolts within the theology of just war. Brown raised this question in my mind, but this isn't a post aimed at justifying any of Brown's violence. Yet Brown's goal in attempting a slave revolt to overthrow American slavery presents to just war theory an atypical case study that I haven't seen a whole lot of reflection about. According to just war theory, can a slave revolt be justified?

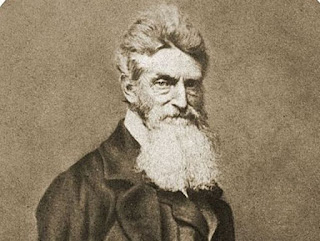

To start, it is very hard to justify the earliest deaths associated with John Brown, the murdering of five people at Pottawatomie in the Kansas territory.

The Pottawatomie murders were a response to the sacking of Lawrence by pro-slavery forces. In retaliation for pro-slavery aggressions in "Bleeding Kansas," Brown and his followers, his sons among them, dragged James Doyle, along with his sons William and Drury, Allen Wilkinson, and William Sherman out of their houses in the dead of night and killed them. The murdered men held pro-slavery views, but themselves owned no slaves. Supporting slavery was enough, so they were killed.

It's very difficult to defend Brown's violence at Pottawatomie. His subsequent violent actions after Pottawatomie, up to and including the raid at Harpers Ferry, are more defensible. Though I'd expect most people would decline to defend any of it.

Which brings me to my question. Specifically, how do Christian just war advocates evaluate slave revolts?

What John Brown was trying to accomplish at Harpers Ferry was a slave uprising and revolt. The plan was to seize, hopefully without bloodshed, the stash of arms held at the federal armory at Harpers Ferry. While that seizure was happening, parts of Brown's party would alert the slaves in the surrounding area. Brown expected the slaves to rally to him. Brown's group and the escaped slaves would then slip away into the nearby Appalachian Mountains. A student of guerrilla warfare and slave revolts, Brown felt a small force of fighters in mountainous terrain could avoid capture and hold off the superior forces of the federal government. From his bases in the mountains, Brown planned to lead raids upon southern plantations to free slaves in an attempt to spread fear and create pressure upon the slave-holding states.

That was the plan, but it didn't materialize. The slaves around Harpers Ferry didn't swarm to Brown and he lingered too long waiting for them, eventually becoming trapped. In addition, the raid didn't avoid bloodshed. Brown and his party killed six people at Harpers Ferry.

Now, was that violence justified? The knee-jerk response, I'm assuming, is to answer, "No." Of course, for Christian pacifists that "No" is a principled unconditional "No." But most Christians aren't pacifists, most Christians, at least of my acquaintance, espouse some form of just war theory, that violence can be justified in the face of evil or used to protect the innocent.

If so, slavery was a great evil. The greatest evil, in fact. And if that's the case, wouldn't slaves using violence to free themselves be justified? How does just war theory deal with slave revolts?

I'm not trying to justify John Brown or slave revolts, but I am asking a question about what I think might be a blind spot in just war theory. Specifically, just war tends to focus on violence between nation states: Can declaring war upon another nation state be morally justified? And can Christians serve as soldiers in such a just war? Many if not most Christians answer those questions in the affirmative.

But what if the situation concerned an evil state, say a state that had legalized slavery? Would the slaves in that state be morally justified to use violence to free themselves?

The question here involves the issue of legitimizing authority in just war doctrine. Generally, only a state can legitimize the use of violence. If so, a slave revolting against the state would be, by definition, an illegitimate and unjustified use of violence. Slaves, in this view, don't have the political authority to declare war.

But, to my eye, that seems to be a contestable conclusion. Yes, the Bible says that slaves should obey their masters. But that command is justified through Jesus' prior example of nonviolence, his turning the other cheek and not resisting an evil person. This is the moral logic of 1 Peter 2.11-25. But according to just war theory, Jesus' nonviolent example and his peace commands do not hold universally. According to just war theory, Jesus' nonviolence can be set aside, which seems to suggest that a slave could also, under conditions, set aside that example. Goodness, the Founding Fathers took up arms against the state because of unfair taxation. But a slave can't take up arms against slavery?

We could also argue that just war isn't the right place to have this discussion. Could, for example, a slave revolt be better described as an act of self-defense?

Perhaps what we are talking about here is something different than just war, and I'm trying to fit a square peg into a round hole. I've started with just war because just war is a location where Christians have done a lot of reflection about the justifiable use of violence. But that body of theological and ethical thought might be ill-suited to address how Christians are to respond within oppressive, evil states. And let's also point out some inconsistency here as most Christians, I'm assuming, are fine with the American revolution. But the American revolution was a revolution, it wasn't a just war between two rival states. The American revolution was an uprising of citizens against their own state.

I'm also very aware that this post is likely making people uncomfortable as we are in a political moment where many on the political left and right, from Antifa to the January 6th insurrectionists, are increasingly justifying violence to achieve their political goals. But this is where some of the reflections from just war theory are helpful as they insist on a moral calculus that considers things like the magnitude of the harm being done and the principle of last resort, where all peaceable means have been wholly exhausted. Losing a democratic election, in either 2016 (looking at you, Antifa) or 2020 (looking at you, Jan. 6th insurrectionists), doesn't seem to, even remotely, meet such standards of justifiability.

John Brown, by contrast, was facing something very different. John Brown was dealing with chattel slavery, enshrined in and protected by the US Constitution. And chattel slavery is, I think we can all admit, one of the most egregious evils in the history of the world. Further, in America it was an evil that, given its constitutional legitimacy and protections, was going to be almost impossible to change via electoral politics as they stood at the time. It was going to take bloodshed to end slavery in America. And it did. The harm was among in the most evil in history, and peaceable means, seen clearly now in retrospect, had been exhausted. So was a slave revolt in that situation justified?

That was the question that kept haunting me in reading David Reynolds' John Brown, Abolitionist.