Over the last year some students and I have been involved in some research into the PostSecret phenomenon. Earlier this month we presented five papers in a symposium entitled The PostSecret Phenomenon: The Psychology of Anonymous Confession at the annual Southwestern Psychological Association conference held, this year, in Kansas City, MO.

Over the last year some students and I have been involved in some research into the PostSecret phenomenon. Earlier this month we presented five papers in a symposium entitled The PostSecret Phenomenon: The Psychology of Anonymous Confession at the annual Southwestern Psychological Association conference held, this year, in Kansas City, MO.

Two of the first questions we had about PostSecret were these:

#1. Are the secrets we find in PostSecret (at the PostSecret Sundays website and in the publications) typical of the secrets you and I might have? That is, is PostSecret representative of the normal population?

#2. Along these lines, is PostSecret sensationalized? That is, as a website and as a publication series PostSecret may be selectively choosing secrets that grab our attention to create more web hits or book sales.

But to answer these questions we faced a challenge. We couldn't do preliminary tests of these questions until we got a handle on the PostSecret "content" (i.e., what the secrets were about). Until the content was ballparked we couldn't move on to how the content of the PostSecret secrets might or might not be representative of the content of "real world" secrets (i.e., the secrets you or I have).

To start this process we examined the content of the three PostSecret publications that were available to us at the start of the project in June 2007: PostSecret, My Secret, and The Secret Lives of Men and Women.

We read through all these secrets and noted that, in our estimation, the secrets could be grouped into three broad areas:

Existential: Secrets related to existential themes such as life meaning/purpose, choice, regret, religious faith, and death.

Relational: Secrets involving relational issues such as fracture, unrequited love, sexuality, isolation, harmony, and romantic anxiety.

Declarative: Descriptive statements about aspects of the the self that are often considered shameful or deviant.

As you can see, after this initial sorting we had sub-codes within each category. Examples and descriptions of these sub-codes follow (click on each for a closer look):

I. Existential sub-codes:

i. Life meaning and purpose: Concerns or hopes about one's overall life purpose or the meaning or value of one's life:

ii. Choice and regret: Negative emotions related to making choices or regret over choices already made:

iii. Religious faith: Secrets related to religious faith, doubts, or loss of faith:

iv. Death: Secrets related to death anxiety or death-related concerns:

II. Relational sub-codes:

i. Fracture: Relational conflict, failure or brokenness:

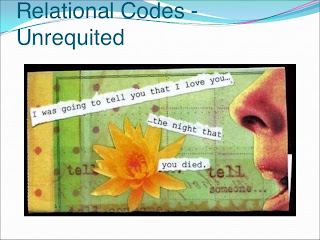

ii. Unrequited Love: Expressions of love that are unfulfilled:

iii. Sexual: A secret about the sexual aspect of a relationship:

iv. Isolation: Secrets about a lack of relationality such as loneliness or alienation:

v. Romantic Anxiety: Secrets about romantic worries or preoccupations:

III. Declarative sub-codes:

The Declarative secrets are all self-descriptive statements, but these tended to fall into one of three areas:

i. Mental Health: Secrets about psychological strain (e.g., abuse) or psychological dysfunction (e.g., drug use, suicide):

ii. Sexual: Secrets about one's sexual interests or behaviors:

iii. Self-Trivia: Undisclosed facts (generally odd, bizarre, shameful or deviant in nature) about one's interests or behaviors:

With this coding complete we could examine the relative proportions of secret content found in PostSecret. This analysis revealed that the most common secrets--what we called The Big Three--were the following:

Existential : Meaning

Relational : Fracture

Declarative : Self-Trivia

That is, the most common secrets in PostSecret are secrets about:

Concerns, fears, or sadness over the meaning, purpose, direction or value of your life.

Worries, anger, or sadness over some fractured or failed relationship with a friend, parent, family member, spouse or child.

Some facet of yourself (some interest, trait, or behavior) that you've never disclosed to anyone because you fear that people will find it odd, sick, bizarre, shameful, or deviant.

In short, if PostSecret is an accurate guide (a question I'll hold over for the next post) we can expect that The Big Three would capture the majority of secrets we all keep.

Does it capture yours?

Further, what can The Big Three tell us about the human experience? That is, if our secrets do cluster in these three areas what can we learn about ourselves? And, does this have any spiritual or theological implications?

PostSecret: Part 2, The Three Biggest Secrets

Next Post: Is PostSecret Sensationalized?

Richard

This is some fascinating research... did you guys pretty positive feedback at the conference? I love psychology research that combines archival methods to understand a problem of interest... as is the case here. Psych outside the lab can be quite interesting! I will be interested to see what type of conclusions you draw on the ending question, "what can The Big Three tell us about the human experience? That is, if our secrets do cluster in these three areas what can we learn about ourselves? And, does this have any spiritual or theological implications?"

Peter

I came across this site accidentially and wanted to chime in...really quite interesting work. What happens when "The Big Three" overlap? Are there further implications to the human experience? Interestingly enough I work with a population in trauma focused care that would have a lot of input into this topic. Very interesting.

M.E. VanBenschoten

Hi Peter,

We did get a good reception at the conference. Many in the audience knew of PostSecret and intentionally came to the presentation on that account.

Regarding my ending questions, I'm still kicking them around myself. My first take is this: Much of our interior life is plagued by a sense of alienation, a disjoint between me and life. This manifests itself in existential alienation, interpersonal alienation, or a generalized sense that one is "odd," "strange," or "deviant."

M.E.,

The content of the secrets do overlap a lot. In the study we actually gave dual codes if the content tapped into two areas.

So is it alienation that results from a cultural code where certain things are taboo and would potentially result in rejection... or is it an alienation that would remain even if the secrets were exposed? In other words, I wonder if expressing the secrets minimizes (or removes) the alienation?

Hi Peter,

My hunch is that this sense of alienation is a product of human interiority. That is, due to human cognitive capabilities we have "external" and "internal" lives. Much of our internal milieu is hidden and, I'm guessing, this is the source of the disjoint we feel in life. From Freud: To be human is to exist as a neurotic animal.

An essay on this topic that has influenced me is Thomas Nagel's Concealment and Exposure.

Fascinating....what can the big three tell us about human experience? imho, people are more alike than different...another interesting question: why do so many people mail secrets to a stranger? This is a big question...many of the secrets I *do* believe are sensationalized...and many of the secrets only increase my compassion for the writer...and I'm glad I have friends and don't feel the need to send secrets...at least not today...

Thanks for that link, Richard. "Concealment and Exposure" was a great thing to read: It raises some very important issues to think through.

In the brief time since I've read it (really, just a couple of minutes!), it's gotten me to thinkin' about social relations at churches. For the general reasons Nagel brings out (though he never addresses what happens at churches in particular), it would be disastrous for us to "let it all hang out" at church. Still, it seems that churches, or at least smaller sub-groups within churches, might be settings in which a certain kind of intimacy is desirable -- where certain things that are concealed in most other settings can be safely revealed. But characterizing the different types of arrangements that might be desirable is a big task I won't take up here. Just wanted to point out that Nagel's paper presents a nice framework for thinking about such things.

I'll also quickly express the suspicion that a lot of people who find themselves strongly disliking churches (or at least the churches their parents dragged them along to as children) might feel as they do largely because they experience church as a place where they have to be concealed to a great degree & in an especially dishonest way -- a place where they experience an unusual amount of pressure to express beliefs & attitudes that they don't authentically hold & have (& that concern especially important matters). In some ways, church can resemble the bad family gatherings that Nagel describes: "There are also relations among these phenomena worth noting. For example, why are family gatherings often so exceptionally stifling? Perhaps it is because the social demands of reticence have to keep in check the expression of very strong feelings, and purely formal polite expression is unavailable as a cover, because of the modern convention of familial intimacy. If the unexpressed is too powerful and too near the surface, the result can be a sense of total falsity.")

Perhaps many of those who are seeking to establish some kind of non-traditional or different types of churches (or sub-groups within existing traditional churches) -- and especially those who use the word "community" a lot in describing what they're hoping for -- are seeking to correct just this problem. If so, this paper may give them a way to think through some of the issues they will have to face. Just what kinds of intimacy / openness are they seeking, and what will be left concealed? (and the answer to that question can't be "nothing," it seems). There are huge challenges here, once you get enough people with different needs & in different conditions that are trying to form a community of at-least-in-some-respects greater-than-usual intimacy.

Since I expressed strong enthusiasm for Nagel's paper, I should also register that I pretty strongly disagree with some of the ways Nagel himself takes things. To his credit, he anticipates the main disagreement I had -- in the paragraph that begins with the words "The natural objection...": I was disappointed to find my objection was so predictable! -- and he does answer it. But I remain very worried by the conservatism of his application of his own general approach. On issues like whether we should use "he" as a gender-neutral pronoun, he at times seems to think that it's only those who take one side of that issue that are getting into other people's faces, while those who stick to the old ways are thereby excused from that sin. I would have thought the way to handle such a situation is for people to decide how they wish to speak in this respect, but to show a lot of tolerance for those who choose differently.

Finally, I loved his description of the state he'd like us to return to on the issue of different religious (or a-religious) views:

We would be better off if we could somehow restore a state of truce, behind which healthy mutual contempt could flourish in its customary way.

I should add here that Tom & I were colleagues at NYU philosophy (though he spent much of his time over at the Law School) for 3 years (1990-93). He was there long before me (and is still there now), so he was in that predominantly atheist department when they decided to hire this openly Christian philosopher (though I don't know how much a role, if any, he played in that hiring decision). I thought my relations with Tom & the rest of the department were excellent, and always thought that I was treated more than fairly there. But now I have to wonder whether these relations were all, from Tom's perspective, a matter of "healthy mutual contempt"! (Actually, I can't believe that: but I am wrong here, I don't think I want to find out!)

Jesus taught that one day "everything that is hidden will be revealed" so in the long run, there won't be any secrets. I'm not sure how all that will work (will everyone learn everything? Will we learn about the Kennedy assassination, etc.?) but what I also wonder is how will we be transformed to handle this information? I don't believe we (at least not I) could currently handle this info in my present state of being. I'm positive there are secrets related to me or those I love that I don't want to know and I'm better off not knowing them. It goes back to that "what if you could read minds" question. Few would really want to have this ability and if you did it is likely it would lead to a complete mental breakdown.

However, it does appear that at least in his later ministry period Jesus had this ability to some extent. He knew about the woman at the well. He knew her secrets. He knew what was in the hearts of men. I would propose it is his knowing this that lead him to weep over Jerusalem. So what was it about Jesus that allowed him to cope with this ability? I would propose it was because he had "emptied himself, becoming nothing". He knew who he was and knew where he was going. What others thought had no impact on him as a person other than moving him to compassion. It didn't impact how he saw himself I don't believe.

So, I guess what I'm saying is that we have and need secrets and we need others to keep secrets to the extent that we wrestle with our own doubts about who we are and where we are going. If those questions are answered in a positive and affirming way than secrets aren't as important anymore.

ld,

One of my favorite quotes from the psychologist Carl Rogers is "That which is most personal is most general." That is, we tend to think that the deeper we go into our own soul we will find the things that are only unique to us. But according to Rogers, we generally only differ in the superficial. The deeper we go into our own souls--the content of my life I feel is so very unique to me--the more we find what is actually shared by all humanity. We all want and fear the same things.

Keith,

Thinking along with your ecclesial observations...

In my experience the main interventions to create more community, authenticity, and relationality in churches have been: 1) a confessional pulpit and 2) small group ministries. Regarding the former, a transparent and confessional priest or minister, I think, creates a more "real" and transparent atmosphere. Even the way he or she dresses can have an impact. "Dressing up" for church has some pernicious consequences. This more confessional style, in my opinion, is one of the fresher contributions coming from the emerging church. Second, small group ministries seem to be places where people can find authenticity. However, small groups are problematic. First, they tend to suffer from homophilia. Which means that the real skills of community--cultivating a love of the stranger--never get developed. We just end up hanging around people like us. Second, once formed the groups can be cliquish and resistant to welcoming new people. Finally, it is hard to create and form effective small groups. Throwing strangers together isn't always effective. Chemistry is an issue. Which brings me back to homophilia.

So, I'm with you. Churches face some serious challenges. And I think you are right about the usefulness of Nagel's essay. Too often we throw around the word "community" without fully realizing what the implications of intimacy truly are.

Daniel,

That's an interesting line of thought. In our literature review on this subject we found research on secret sharing that suggested that people, after they make a disclosure, do experience rejection. That is, sharing a secret is risky. It can be socially costly.

The point being, I like the line of reflection you've opened up: How are we to receive a secret? What kind of person do I need to be? What kind of skills might I need?

In my church tradition we have totally lost the art of receiving a confession and granting absolution. I think if we recovered this ability our love and compassion with each other would grow the more we disclosed.