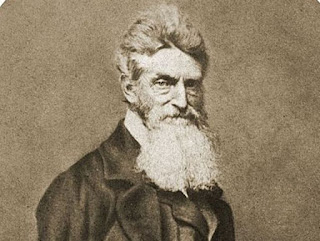

If you've ever thought about John Brown you have likely formed some impressions and opinions about him. Most people assume he was insane, a violent religious fanatic and zealot. I'll get to the violence in my third post of this series. But regarding his sanity, Reynolds' assessment is forceful, persuasive, compelling, and clear: John Brown was sane.

More, there are many things to admire about John Brown. And here's the best of them: The universal assessment of the black folks who knew John Brown intimately and well was that he was the least racist person in America.

What's noteworthy about this fact is that the America abolitionist movement was steeped in racism. The (near) universal assumption among the abolitionists was that, while blacks should be emancipated, this did not mean that blacks were the equal of whites. Most abolitionists, even the most radical, still held the black "race" to be inferior to the white. Being anti-slavery didn't mean you weren't racist. Most abolitionists were racist.

John Brown was different. Singular, even. Brown treated black folks as absolute equals--morally, spiritually, and intellectually. When it came to transcending racism John Brown was in a class almost by himself in the American political and religious landscape. Brown's moral witness in this regard is truly remarkable. Almost, given his time and place, unfathomable.

But it gets even more interesting. Brown's absence of racism was driven wholly by his Christian convictions. The least racist person in America became the least racist person because he was a devout Christian.

And some of the stories in this regard are mind boggling. One of my favorites is how Brown and his followers freed eleven slaves in Kansas and then transported them over a thousand miles to Canada. During the journey they took some pro-slavery prisoners in "the Battle of the Spurs." To lessen their chance of escaping, Brown made the prisoners walk. But Brown, not wanting the prisoners to feel that they were being punished, chose to walk in solidarity beside them, all the while lecturing the prisoners on the evils of slavery. You'd think that would annoy and alienate his prisoners. But something interesting happened on that journey. The prisoners elected to join Brown and his party in their evening and morning prayers. I find this story utterly charming. After his release, one of the prisoner's declared that John Brown "was the best man he had ever met."

I found all this fascinating as we all know that slavery was a big theological debate before and during the Civil War. See Mark Noll's book The Civil War as a Theological Crisis. As we know, the Bible was used to both attack and defend slavery. Same holy book, two different moral verdicts.

Whenever I look back at historical moments like this, I always ask myself the question: Which Christians got the Bible right at the moment of crisis? And which Christians got it horribly, even wickedly, wrong? For example, in the face of Hitler and the Nazis I look to people like Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the White Rose as Christians who got it right. In a similar way, in the face of American slavery which Christians got Christianity right, and which got it wrong?

It's hard not to read Reynolds's book and conclude that on the questions of race, slavery, and human equality John Brown was one of the the best white interpreters of Scripture in the history of the United Sates. On these issues, as a white reader of the Bible, Brown absolutely nailed the hermeneutical question in a way unparalleled in American history.