The first facet, described in Part 1, is how the prophetic imagination hears the voice of God as a message of divine solidarity with the victims, the weak, and the oppressed. This is Moses telling Pharaoh, "Let my people go!"

The second facet of the prophetic imagination, described in Part 2, is hearing the voice of God in moral self-criticism, attending to how we ourselves have become Pharaoh, how we hurt and victimize others.

The final facet of the prophetic imagination that I share with my students is how the voice of God interrupts our hate.

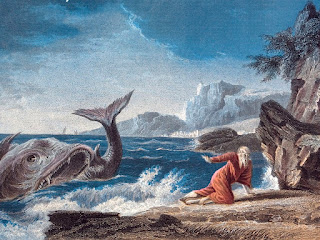

The classic example here is the book of Jonah. We tend to think that the story of Jonah is a whimsical folktale about a whale. In my opinion, however, Jonah is one of the most outrageous, scandalous, shocking, and radical documents ever written. How the book of Jonah got included in the Bible is mind-boggling.

Jonah, you'll recall, is to preach a message of repentance to the Assyrians, an opportunity for grace. You'll also recall who the Assyrians were. The Assyrians were one of the most violent and brutal empires in the ancient world. And they commit genocide upon the ten northern tribes of Israel, conquering them and taking them into slavery where they are never heard from again, lost to history. Ten tribes, vanished, gone.

Of course, Jonah says "Hell no" and runs the other way. He wants no part of extending grace to his enemy. And yet, God forces him to go. And grace does come to Assyrians, causing Jonah to rage and fume. And in the face of Jonah's spitting anger God asks Jonah, and through Jonah all of Israel, this haunting question: "Should I not have compassion on this great city?"

That's how the book ends, with that question, just hanging there. And that's really the whole point of the book of Jonah, to forever lodge that question in the moral consciousness of Israel. That question--"Shall I not have compassion on these people you hate?"--is like a moral thorn in the brain, a question that pricks, haunts, disturbs, and interrupts our easy hatred.

That is the prophetic imagination in the book of Jonah, the moral thorn and the haunted conscience, the voice of God asking us to have compassion on those we hate.